“You start with an idea in your head, and you take a step, then a second. Soon, you realize you’re up to your neck in something intense, but that doesn’t matter. You keep at it for the sheer pleasure of it. For the pure satisfaction it might bring you.”

The Vanishing, directed by George Sluizer, shakes up a conventional formula with steady self-assurance. It takes a familiar scenario—a kidnapping—and subverts the standard plot structure that typically follows it. Instead of focusing on the search for the kidnapper, the film spends its time exploring his life. Revealing the identity of the villain early in the film allows Sluizer to come at the mystery from a different angle, one that is harrowing in its nonchalant sketch of the madman and refreshing in its atypical narrative choices. It doesn’t have the iconic appeal of films like Halloween or Psycho but its climax is more frightening than anything I’ve seen in the “conventional” horror genre in a long while.

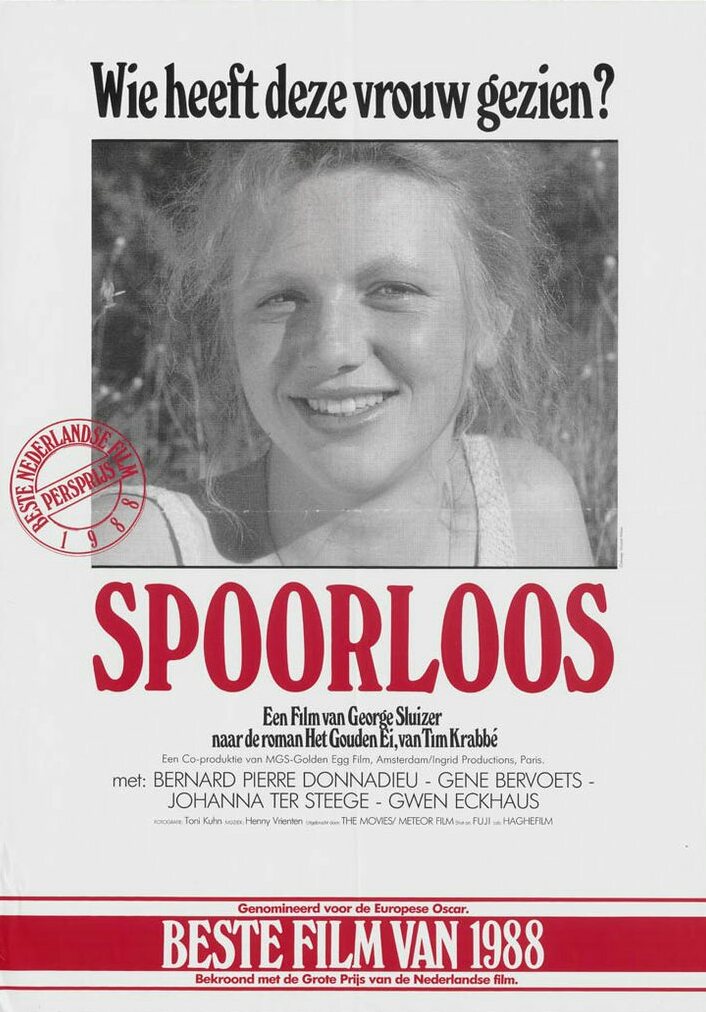

Titled Spoorloos or “Traceless” in Dutch, the film is based on Tim Krabbé’s novella The Golden Egg. Sluizer secured the rights before the book was even published and the two combined their minds to craft the screenplay, resulting in a fresh take on a well-worn genre. The film’s opening scene is a fairly standard one—a young couple are on vacation in the south of France; they stop at a gas station for a bathroom break and drinks. When Saskia (Johanna ter Steege) does not return to the car, Rex (Gene Bervoets), a foreigner, does not know what to do. She has simply vanished. If the screenplay was going to follow a standard arc, Rex would come up with some kind of clue here at the rest stop—but we don’t see Rex until three years later and we only see Saskia in flashbacks.

We stray even further from convention by skipping the crime altogether. We know that Saskia is gone but not how or why or if she’s dead or alive. We are quickly transported from the scene at the gas station into the past of psychopath Raymond Lemorne (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), a man who calmly, chillingly leads a double life. He has a wife and children and is fixing up an old house in his spare time; he also experiments on himself with chloroform, calculates how far he can drive until his victim awakens, and practices the words and maneuvers that he will use to lure a woman into his car. His socially adept and intelligent demeanor masks the fathomless evil lurking behind it.

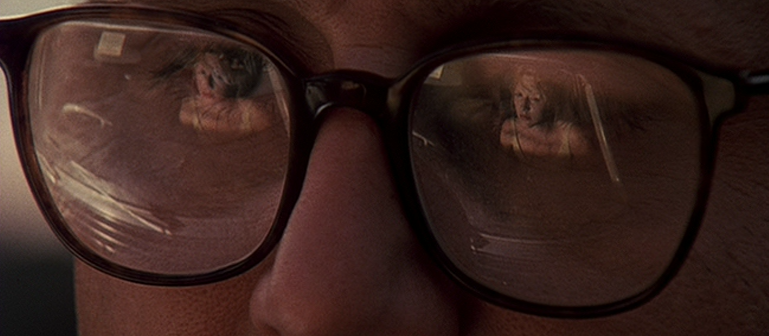

His relationship with his family is petrifying because he is clearly thinking about the planned abduction all the time, even when he is goofing off with his daughters or teaching them moral values. His wife and eldest daughter suspect he is having an affair, but they still appreciate the love and support he gives them. There are some smartly written scenes that economically illustrate his obsession. At the abandoned house, his daughter gets spooked by some spiders; he takes advantage of the situation by encouraging a family screaming competition. The next day, he checks with the neighbor to ensure he had not heard anything unusual—confirming that the house is totally isolated. In another scene, he picks up his eldest daughter, Denise (Tania Latarjet), from school. As she gets in the car, he smoothly reaches behind her and locks the passenger door. Then he puts her in a headlock and gives her a noogie—a maneuver we had seen him practice on his own with a chloroformed handkerchief in his hand. These scenes demonstrate that this is not a man suffering from multiple personality disorder or dealing with bouts of hysteria; he is always thinking of his evil pursuit.

Sluizer understands the formula of the genre he is working in, but dismisses its restraints as artificial. In a conforming whodunnit, the bulk of the time would be spent uncovering the identity of the villain and their motives for committing the crime. But because we don’t actually witness the crime until the end of the film, and our villain quickly becomes the main character, our empathy and interest are divided. Raymond’s desire to pick up a woman is narratively viable—that is to say, although his aim is clearly perverse, it is presented in a way that we are conditioned to support. His pursuit is detailed in long takes with sparse dialogue; he tries and fails several times to snare a victim. Sluizer’s detached style almost makes Raymond’s horrid activities seem like a farcical pastime. And because he is characterized as a likeable family man, and we don’t yet know what happened to Saskia, we want him to succeed! We need him to succeed to solve the mystery of the first scene, and all our moral hang-ups are dismissed in pursuit of this knowledge. And that slight twist—generating a desire to know what happened instead of why it happened—keeps the audience captivated.

Rex briefly re-enters the narrative three years after the kidnapping. Mirroring the anxiety of the audience, he is still entirely consumed by Saskia’s disappearance, plastering posters of her face on telephone poles and bulletin boards. Several times, he has been invited via anonymous letter to meet the kidnapper at a cafe, but the man has not shown up. After he goes on public television and makes a plea, Raymond confronts him in the street and makes an offer—come with him immediately and learn of Saskia’s fate, or Raymond will disappear forever and Rex will never know what happened. Crucially, ter Steege’s performance in the opening scene imbued Saskia with such vitality and presence that Rex surrendering himself to a madman three years later seems like a reasonable chance to take.

Where before we were given only glimpses into Raymond’s mind through his disturbing actions, we now take a full-on plunge into his psyche as he recounts the childhood experiences that led him to play games with fate. Gradually coming to understand that he lacks the conscience that guides most people, he elects to commit the most heinous act possible to see if it will affect him differently than doing what is commonly perceived as good. If Raymond were a standard movie villain, this explanation would feel tiresome and conceited; but Donnadieu plays him like a passive, mild-mannered chemistry teacher who is intrigued by the curio of his unique condition. The portrayal is bone chilling; straight-faced, inhuman evil not dissimilar to Anton Chigurh (No Country for Old Men) or Colonel Hans Landa (Inglourious Basterds).

The Vanishing lands its biggest gut punch by convincing us that Rex’s life is expendable if it means we will be given closure on Saskia, i.e. Rex’s death—as long as it occurs on screen, of course—is an easy price to pay if it means we will uncover the mystery of Saskia’s fate. Having teased us with who and why, we willingly sacrifice Rex to learn how Saskia met her end. Raymond drives Rex to the rest stop where Saskia was last seen and offers him drugged coffee. Rex is told that when he wakes up, he will find out exactly what happened to Saskia. As Rex fades into sleep, the scene of the kidnapping is finally presented to us. The success of The Vanishing mostly rides on its sequencing and use of ellipses, but this scene stands out for its excellent scripting and acting. Raymond improvises a line and poses as a tchotchke salesman, and Saskia, barely able to speak French, fumbles with the language as she requests to buy a trinket for Rex. I don’t know how much of the stuttering and non-verbal actions were written in, but Johanna ter Steege completely owns it.1

Understated but pivotal to the film’s success is its atmosphere. Several elements give The Vanishing the haunting aura of a daytime-nightmare, such as the repeated descriptions of a mystical dream of two golden eggs in outer space; surrealistic imagery of tunnels, headlights, and computer glitches; inescapable commentary on the Tour de France from the radio and television; and Hennie Vrienten’s eerie soundtrack. But it is the film’s layered construction that gives it staying power—its myriad motifs, its hidden-in-plain-sight clues that we miss the first time around, and its out of sequence storytelling method. It’s a carefully written and edited film that has more intricate wrinkles than a mere discussion can elucidate.

The Vanishing manages to provoke its audience and explore things from a novel angle while remaining an enthralling mystery. It forces the audience to assume the roles of both victim and perpetrator, and its sustained horror—which Stanley Kubrick considered more frightening than The Shining—which is punctuated by a gut-wrenching denouement, remains firmly lodged in the mind long after the jump scares and gore of a regular horror film would have faded from memory.

1. It’s a shame that she never got to make it big as it seems like she could have exceled. She was cast as the lead in Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Wartime Lies—a film that was ultimately cancelled in wake of Schindler’s List—but never got the big role she deserved.

Sources:

“Johanna ter Steege on Stanley Kubrick and his unmade film THE ARYAN PAPERS”. Youtube, Eyes on Cinema. 5 July 2016.