“They flee womanhood like a house on fire.”

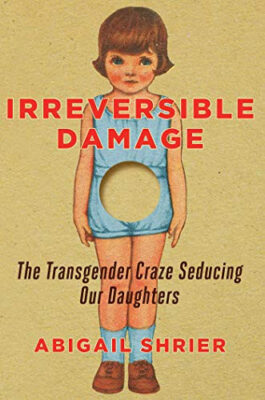

Abigail Shrier’s Irreversible Damage offers a fair, clear-headed critique of the recent trend of adolescent girls identifying themselves as transgender, viewing it less as an expression of true gender dysphoria (a legitimate condition that usually amounts to a “phase”) than a social contagion driven by recent developments in online culture (social media, YouTube, easily accessible pornography) which gives girls with other mental disorders (social anxiety or bipolar disorder, for instance) a chance to bank instant social capital by claiming an oppressed identity.

It’s a hot-button issue with strongly held opinions on both sides, but Shrier does a good job of presenting facts, data, and anecdotes to suggest that permanently altering the bodies of children during a psychologically tumultuous phase of their lives is not in the best interest of any individual child nor society as a whole. And yet, due to political and social pressures, medical doctors and professional therapists are falling in line, allowing patients to self-diagnose and receive almost immediate treatment, whether chemical or surgical.

There are people who claim the name of Christ who support young girls having their forearms mutilated for the slim chance that a doctor might be able to successfully graft something resembling a penis into their nether regions—but as a Christian, I am tempted to say that Shrier’s book highlights a need to return to biblical truths about gender and identity, about the definition of love, about our identity in Christ, etc. The book itself doesn’t make that case. It does, however, prompt a return to biological and medical truths about these things; one need not be a Christian to take a stance, just a person with a rational mind.

Shrier’s work is filled with anonymized personal stories that illustrate how the transgender movement has evolved from a desire to “pass” as the opposite sex to a public celebration of deviance from the norm—the weirder the better—often propped up by a culture that paradoxically reinforces gender stereotypes to justify itself (i.e. they need gender to both be and not be a “spectrum” in order for their scheme to work). Her critique of educational and medical systems, particularly the decision by California teachers’ unions to allow children to seek hormone treatments without parental consent, resonates with a Christian worldview that places premium value on the parents’ role in raising their children; whereas the progressive model—and Shrier points out that most of the girls that are affected by this phenomenon are the children of affluent white progressives—puts emphasis on the government’s responsibility to support and provide for their children.

Shrier is respectful of and compassionate toward the individual, as I strive to be as well, spending a lot of time interviewing people from many different subsections of trans culture, from OGs to detransitioners to homosexual guardians of trans kids. And while it is somewhat sensible to respect anyone’s right to choose bodily mutilation as a mode of self-expression in adulthood, the book cautions that such life-altering decisions should not be taken lightly when it comes to children. This is sensible as well.