“It was almost irrelevant because you knew Michael was going to annihilate everybody.”

When I was two years old my parents moved us from a small house smashed between two others in a hillside town, where rubbing shoulders with neighbors was an everyday occurrence, to a brick ranch with a large backyard and a small wooded area. After a few more intermediate moves they settled us down on an old farmstead with trees and fields and streams aplenty (a decision to which I credit my own desire to live in relative seclusion like a crotchety old hermit). Considering my age at the time, I have scant few memories of that first house. I remember the mixed breed mutt that ran away, I remember the swingset in the backyard (which my parents still have, although it’s currently down for service after it tried to catch a falling tree). But my most distinct memory—goodness, it makes me smile just to type it—is marveling at Dennis Rodman’s rainbow-colored hair on the television in my parents’ bedroom. I had no idea who Michael Jordan was. Didn’t know about the first threepeat or his baseball sabbatical. I mean, let’s be real—I didn’t really know what basketball was. But I knew I liked that guy with the funky hair.

The moving date necessarily places my first glimpse of Rodman’s goofy hairdo sometime during his first year with Chicago during the ‘95-96 season. The team would win the championship that year as well as the next. But again, I was oblivious to all this. I just liked seeing Rodman on TV, although at some point I’m sure I was schooled on the history of Air Jordan and recall watching his return to Chicago as a member of the Washington Wizards.

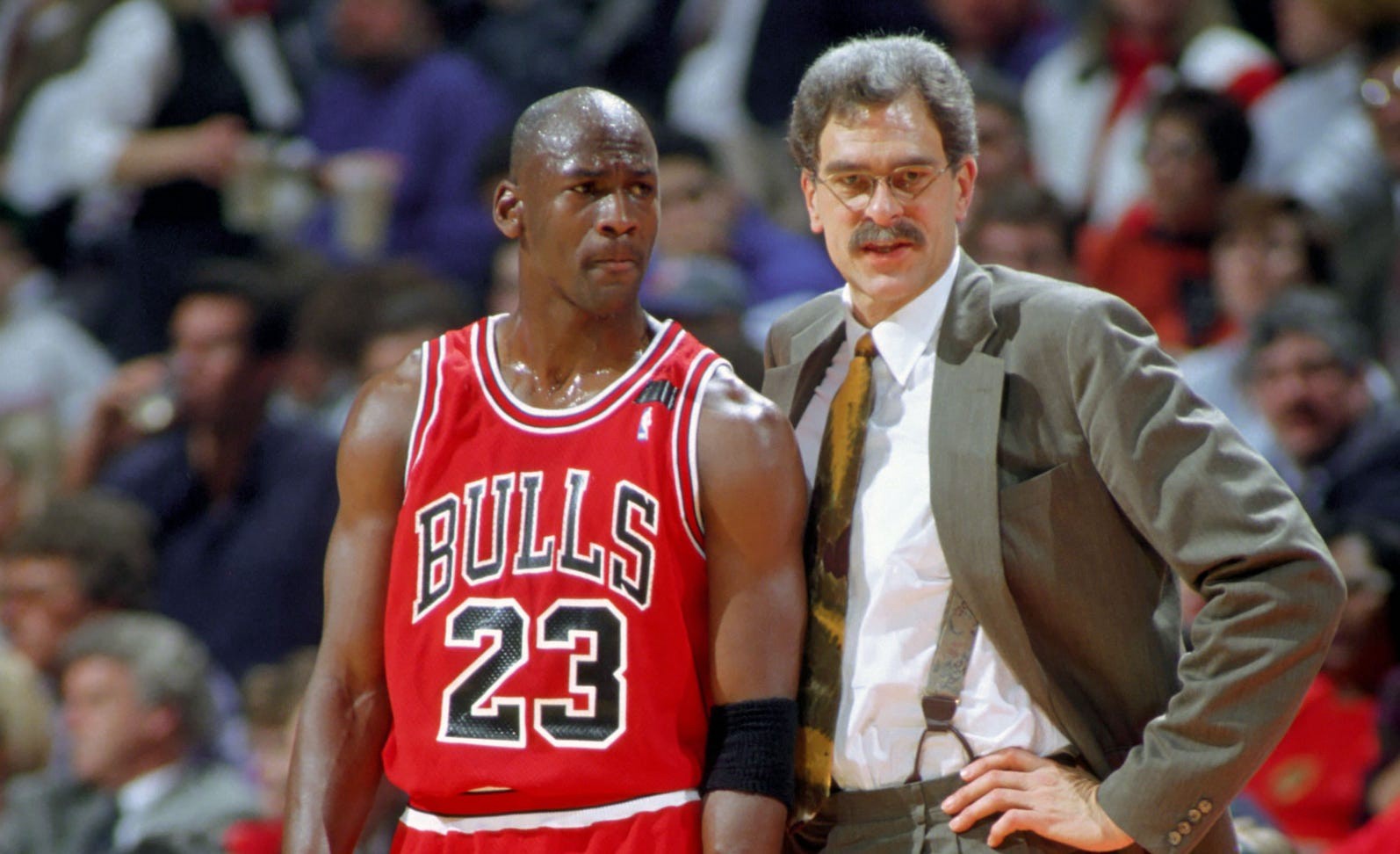

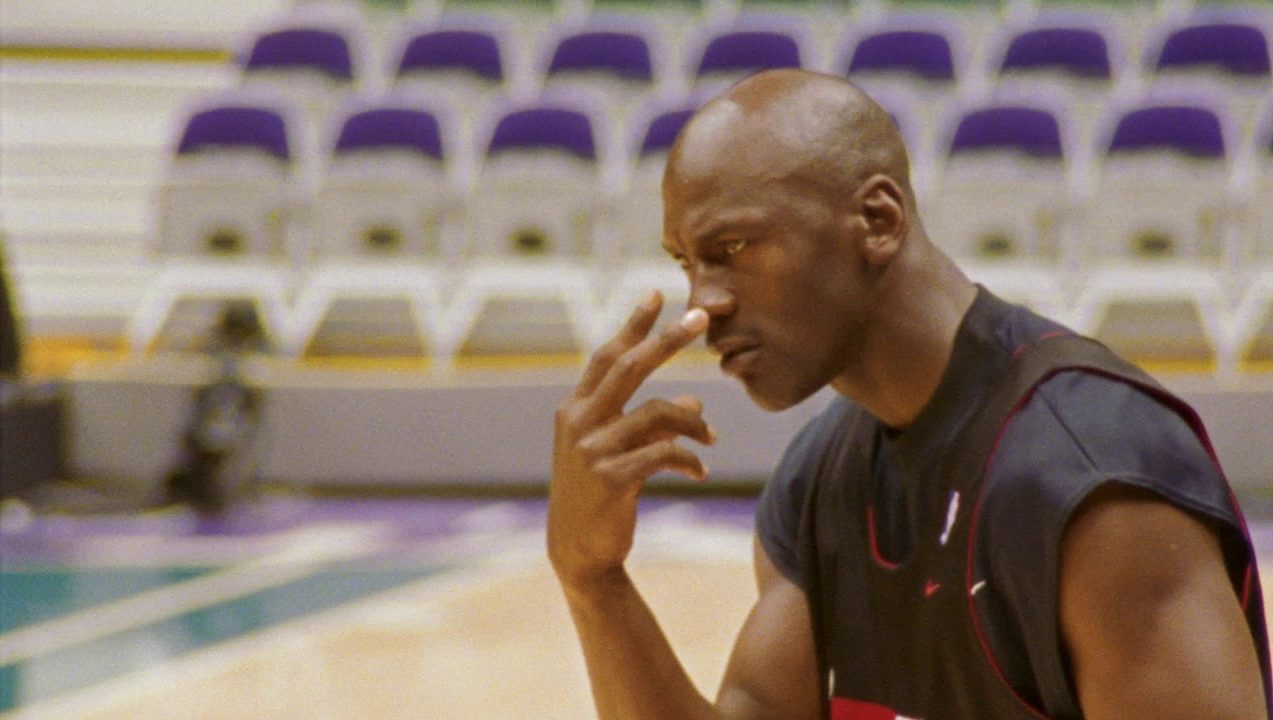

Before the 1997-1998 season even began, Bulls GM Jerry Krause publicly stated that the roster would be blown up at the end of the year in order to kickstart a rebuilding phase. Phil Jackson was also gone come the end of the campaign, even if he led the team to an 82-0 record. And so with that public decision looming over the entire team, MJ and the Bulls embarked on a quest to achieve the unthinkable by capping off a second threepeat. With incredible foresight, Jordan and the team granted a film crew inside access to document his final season both on and off the court on the condition that the footage could only be used with his direct permission. After years of refusals, Jordan finally accepted a proposal for a documentary series that covered his entire career with a special focus on the final run that head coach Phil Jackson dubbed “the last dance.”

With an overwhelming onslaught of highlights befitting such a nonpareil, The Last Dance might fool you into thinking it is something that it’s not. Directed by sports documentary specialist Jason Hehir, the series was produced by ESPN, Netflix, and uh… Jump 23, Jordan’s own production company. In other words, the central subject of the documentary was involved in its making—not a great indicator of integrity. And if you think Mr. Jordan rejected proposals to use this footage for twenty years only to change his mind for a piece of critical journalism then I have a bridge to sell you. That’s not to say that it skips crucial moments that might cast him in a bad light—there are several nasty stories such as when he punches Steve Kerr in the eye in practice. But as the primary interviewee and a behind-the-scenes producer, Jordan is given leeway to shape the narrative and correct the comments of others. In several instances, Hehir does an interesting thing where he interviews a person—say, Gary Payton or Isaiah Thomas or Reggie Miller—and then plays that interview for Jordan and lets him react. If the story is “right” per Jordan’s preference, it receives a wry chuckle and a nod. If it’s “wrong” he sets the record straight. According to the documentary, no player ever got the best of MJ, even momentarily.

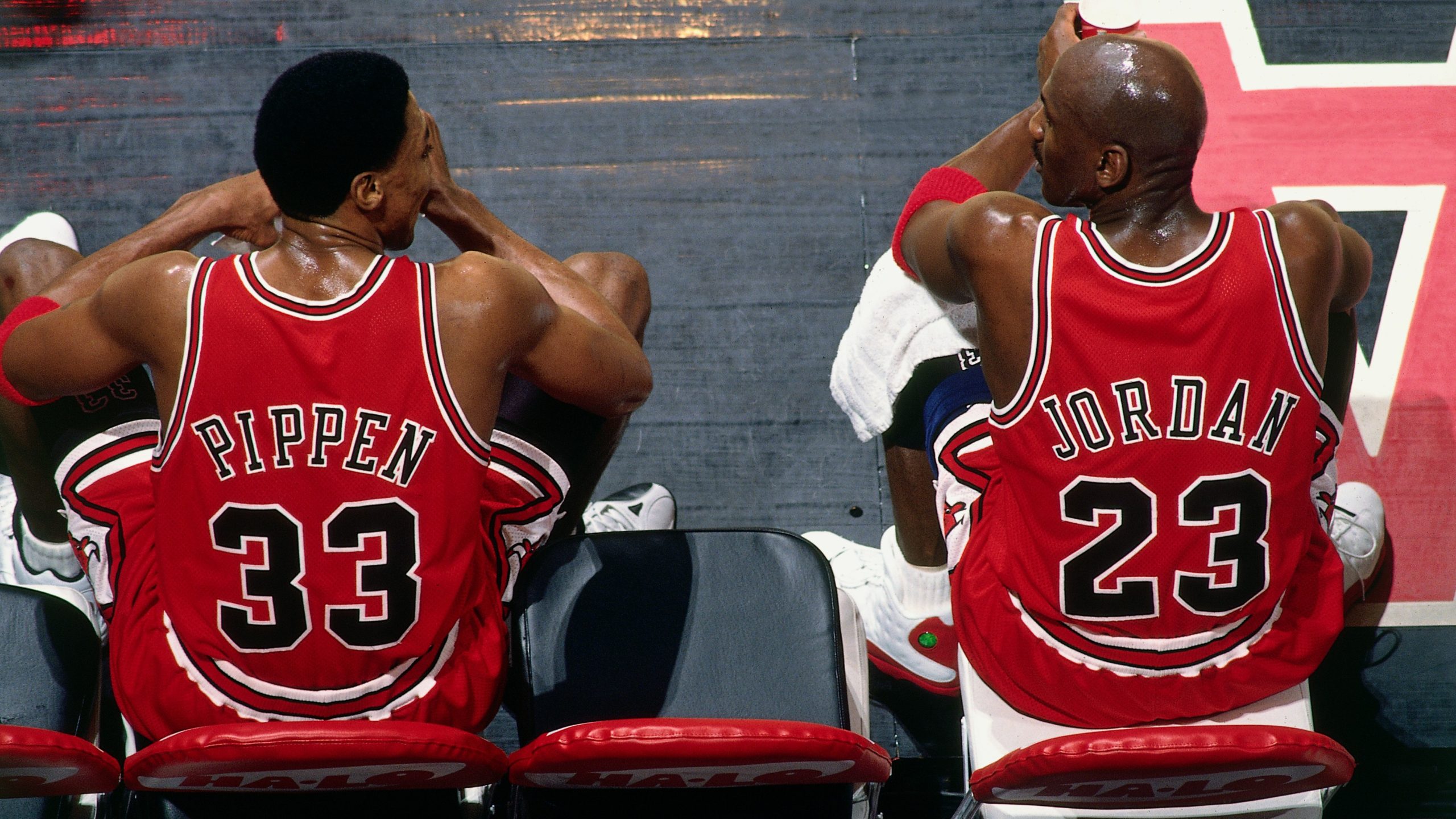

Additionally, the doc touches on a number of potential controversies throughout Jordan’s career—the flu/hangover game, the secret gambling suspension/mini-retirement—and in each case Jordan is given the last word on the matter, often putting a positive spin on his poor behavior. Consider how ruthlessly and consistently he harasses Scott Burrell only to brush it off as a facet of his leadership style. Several outspoken teammates felt that the whole thing was just a puff piece. Horace Grant, who won three titles with Jordan and was interviewed for the series, referred to it as a “so-called” documentary and said, “It was entertaining, but we know that about 90% of it was BS in terms of the realness of it.” Scottie Pippen, who catches flak for several past decisions, released a book of his own to set the record straight. He even accused Jordan of using the documentary series to “uplift and glorify himself.” He said this to the man himself, who replied, “Hey, you’re right.”

But so what if it is self-written hagiography? So what if it is Jordan’s self-mythologizing narrative of his own life? Does that mean it’s not worth watching? Not at all. Despite the huge blow dealt to its credibility by Jordan’s evident involvement, The Last Dance is bigger than Jordan himself. In many respects, it’s a perfectly veracious account. It covers the meteoric rise of the NBA as a global brand, the underdog Bulls teams of the ‘80s and the dynasty of the ‘90s, the hidden stories of Jordan’s inner circle, the childhoods of Jordan’s teammates, the success of Jordan Brand shoes, the commercials with Spike Lee, Phil Jackson’s zen philosophy, the Dream Team, the legendary pickup games during the filming of Space Jam, Tex Winter’s triangle offense, Jordan’s stint in minor league baseball (during which Jerry Reinsdorf, owner of the Bulls and the White Sox, paid Jordan his basketball salary), Rodman’s trips to Vegas and a Hulk Hogan “wrastling” match in between playoff games. These events are conveyed via archival footage, sometimes grainy, sometimes gorgeous, often incredibly immersive, interspersed with contemporary media to elucidate the world’s obsession with Jordan and the Bulls. There are also present-day interviews, but aside from a host of talking heads, trainers, agents, opponents, executives, etc. who provide the necessary context to set the stage for the historical episodes, the only crucial interviewee outside of Jordan is Rodman, not only because his semi-coherent ramblings are played with minimal editing even when they flatly contradict Jordan’s explanations but also because his tangents are incredibly entertaining when juxtaposed with old footage of him riding motorcycles and whacking people with folding chairs midway through the NBA Finals.

The primary subjects of Hehir’s documentary are Michael Jordan’s competitive spirit, charisma, and celebrity and the sport of basketball. It wisely avoids dwelling for too long on anything that detracts from those central topics. When it does momentarily diverge from the main thread, it produces several incredibly poignant moments as well as a number of regrettable foibles. For instance, I really enjoyed learning about Rodman and Pippen’s impoverished upbringings and their unconventional paths to success in the NBA (both attended non-NCAA schools as walk-ons); the politically-motivated murder of Steve Kerr’s father; the compassionate relationship between Phil Jackson and Rodman; even something as simple as Jordan competing (and gambling) in a coin-tossing game with his security guard.1 But ESPN has frequently used the enormous platform they’ve gained as a sports broadcast company to produce sports documentaries that are actually about politics and unfortunately The Last Dance doesn’t totally avoid such shenanigans. Neither does it refrain from interviewing celebrities simply because they’re celebrities. Consider Justin Timberlake’s brief appearance to talk about shoes, or Barack Obama whose title reads “Former Chicago Resident.” These cameos are not to add substance but to prop up the subject with the weight of their own popularity.

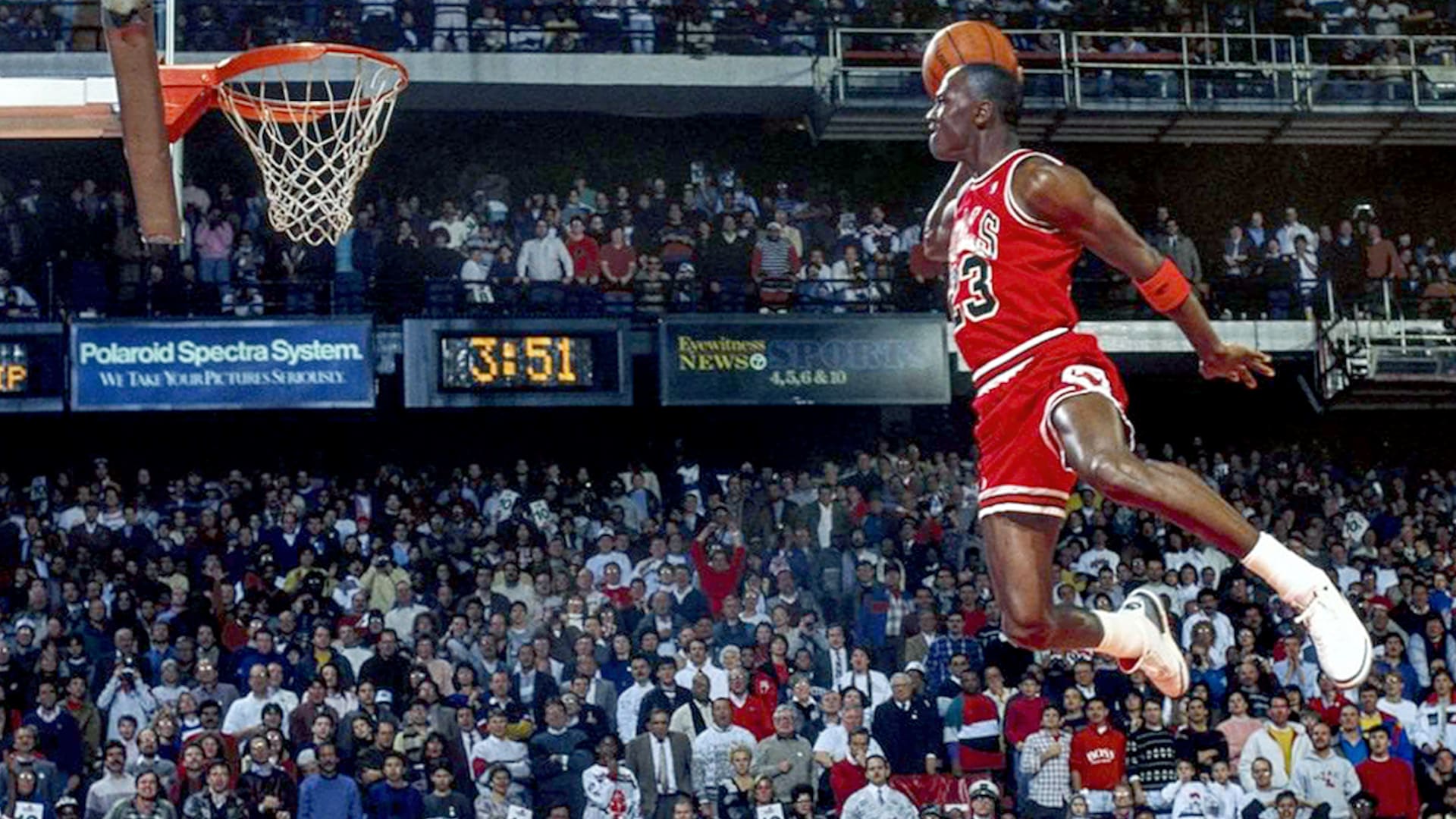

But it never runs too far afield, always returning to the magnetic force at its center—the enigmatic figure who transcended the sport of basketball and became an international icon even while fiercely clinging to his privacy and remaining mercurial and elusive. And even though Jordan’s fingerprints are all over the narrative and discussion topics, he can’t be aught but himself when he’s interviewed. And so even while he sketches out a gilded vision of a hyper-competitive, uber-talented, laser-focused, transcendent generational athlete, you can’t help but feel some level of pity for a 50-something man who exhibits true hatred for another 50-something man who wouldn’t shake his hand after losing a playoff series.

Indeed, one of the most compelling throughlines in The Last Dance is the contrast and cooperation between Jordan’s competitive nature and his thin-skinned sensitivity. Time and again, with perfect clarity he recounts the mentality with which he approached a particular game or matchup, describing how a player mocked him, a coach stated that he had a scheme to beat him, a talking head compared a rookie to him, etc. and how he used those tiny slights as motivation. He tells us that one of his best single-game performances came when someone didn’t greet him at a restaurant. Others describe the time LaBradford Smith scored 37 points against Jordan in the first game of a back-to-back between the Bulls and the Bullets. He said, “Nice game, Mike,” and then Jordan came back the next day and scored 36 on Smith in the first half alone. Turns out, Smith never said anything to Jordan. He simply made up the story to motivate himself. Stories like these give rise to interesting questions: Was Jordan so far above the competition that he had to make up challenges for himself? Did he need to make things personal in order to succeed, or was his unmatched talent simply paired with a tendency to hold petty grudges? If you need personal enemies to succeed in such endeavors, is it worth warping your personality to such a degree to achieve it?

This dichotomy is also apparent in how he handles the media attention. After rising to superstardom, each moment spent outside of his private hotel rooms means dodging reporters and paparazzi or else putting on the charm for them. His demeanor is not rigid. In fact, he’s quite loose with the press—smirking, hinting, teasing. But even as he rarely reveals what he’s thinking or feeling, nightly newscasters rapturously read from the teleprompter about the most minute details of his life. How could such a lifestyle not wear on a person? He takes several pointed shots at journalists in his present day interviews, namely the author of a tell-all book and a negative Sports Illustrated article about his time in baseball. His complaint is not that these accounts exist, but that he was not asked to share his side of the story. In a way, The Last Dance logically results from his competitive spirit and sensitivity now that he’s had time to contemplate and shape his legacy. (It’s fair to note that his second comeback and his years as an NBA executive are not mentioned.)

As the ten episodes unfold, we delve ever further into Jordan’s pathology. These layers are uncovered not for comment but to assert dominance. It’s worth noting the context in which The Last Dance was released. Newer basketball fans will be more familiar with three-point savants like Steph Curry or the horrid foul-drawing play of James Harden than with Michael Jordan’s style of play. But the catalyst that finally prompted Jordan to step up and produce The Last Dance seems to have been LeBron James, a generational talent who won his fourth title shortly after the series’ release. Comparisons between the Bulls’ more organic approach vs. LeBron’s mercenary super team style aside, the documentary seems tailor-made to undercut James’ twilight years in Los Angeles by making an insurmountable case for Jordan as the greatest player of all time—a man who’s reached a peak that has yet to be surpassed. And again I say, so what? It may be shallow and self-centered and prove that MJ is unable to rise above his own ego, but it makes a solid case! It reveals that even now, nearing his sixtieth birthday, Jordan is incapable of removing himself from competition. He still holds grudges and still wants to assert his will over his opponents. It’s an attitude that won him on-court accolades and championships and adulation but is also why he alienated so many who were close to him. As a whole, the series promotes this ruthless mentality that provides a rush in the moment and probably cements Jordan’s status as the greatest to ever lace ’em up, but it also, perhaps accidentally, shows us the hollow nature of such a mindset.

And yet I found Jordan’s unwavering focus on himself and his craft to be (oddly) refreshing. Though he was a magnetic player, it is clear that his charismatic media persona did as much for his larger-than-life image as his game. The man is clearly a narcissist, but aren’t all celebrities? It struck me midway through the series that Michael Jordan couldn’t thrive in today’s environment. Surely, if a prime MJ was plopped into the modern NBA his work ethic and passion for the game would allow him to succeed on the court, but it seems improbable that he would have the same cultural effect as he did in the ‘90s. Without the constant connection in today’s world of social media platforms, Jordan was given the freedom to be himself—which for him meant honing his athletic genius over the course of a career and treating his on-court opponents as real enemies.2 Only rarely did he do more than smile and play it cool when a camera was on. No one knew—perhaps no one knows—the real Michael Jordan.3 In that less connected era, Jordan took the reins from his predecessors and rode the rising tide of the NBA to global superstardom by simply being himself. In the process, he became a singular megastar who essentially shaped the culture to his own liking. By all appearances, Jordan was the first and last of his kind, a singular force of nature who eclipsed his sport.

1. This moment is truly golden. John Michael Wozniak, sporting a greying mullet and huge glasses, beats Jordan at his own game, takes his money, and then hits him with his own patented shrug.

2. Indeed, watching the brutal highlights of the Bulls-Pistons matchups underlines the severe changes in the physicality of the game. That’s not to say the modern game is easier, per se, but you can kind of understand why these men still dislike one another decades later. You see modern players beat their chests and talk smack during game, but they’re buddies again in the aftermath. Back in the day, it appears many players harbored true animosity toward one another.

3. The rawest moment in the documentary doesn’t come during an interview, but when Jordan breaks down crying in the locker room after winning the ’96 Finals on Father’s Day, his first championship since his father was murdered in 1993.

Sources:

“’Lie, lie, lie’: Former Jordan teammate gives withering assessment of The Last Dance”. The Guardian. 19 May 2020.

Anthony, Andrew. “Scottie Pippen: ‘I told Michael Jordan I wasn’t too pleased with The Last Dance’”. The Guardian. 6 December 2020.