“Well, son, you won’t make much money, but you’ll get more pussy than Frank Sinatra.”

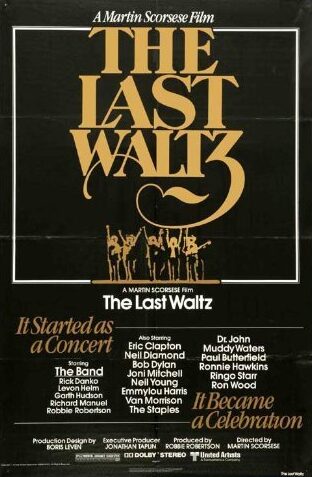

Widely and reasonably held to be the best concert film of all time, Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz chronicles The Band’s legendary farewell concert. Referred to by Robbie Robertson as a celebration of the “beginning of the beginning of the end of the beginning”—whatever that’s supposed to mean—the show was held on Thanksgiving Day, 1976 at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco where The Band had debuted as a group in 1969.

Though they had only been performing under the moniker a short while, the group’s principal players—Robertson, Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, and Richard Manuel—initially came together under the tutelage of rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins as early as the 1950s. Later, they would join Bob Dylan on his first “electric” tour (it was “the Hawks,” as they were called at the time, who responded to Dylan’s instruction to “play it fucking loud!” after the infamous Judas incident), thereafter frequently touring and recording with the enigmatic American icon, who, it must be noted, is still touring in the Year of Our Lord 2025.

Both Hawkins and Dylan join The Band for their final show, alongside an expansive roster of other formative influences and contemporaries that captures the magic of the cultural moment as well as a broad cross-section of musical genres—Dr. John, Paul Butterfield, Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, Neil Diamond (but like, what is Neil Diamond doing here?), Van Morrison, Ronnie Wood, Ringo Starr, Stephen Stills. An early highlight in the film comes when Neil Young plays his own ‘Helpless’ backed by The Band and Joni Mitchell (who sings from behind a curtain, delaying her introduction until her own spotlight performance). “I’d just like to say before I start that it’s one of the pleasures of my life to be able to be on this stage with these people tonight,” Young says as The Band effortlessly shifts from rockabilly to folk. There’s a fortuitous accident when Eric Clapton’s guitar strap breaks loose and Robertson takes over his solo without missing a beat, and a splendid backstage rendition of ‘Old Time Religion’. The closing sequence with Dylan, culminating in ‘I Shall Be Released’ with most of the guest musicians on stage, is a triumphant moment.

Scorsese’s fingerprints are all over the film. Lavish production design, storyboarded camera movements, bountiful close-ups, dynamic lighting. Further, Scorsese inserts himself as an interviewer. These interstitial discussions range from reminiscences about The Band’s impoverished early days to the hardships of life on the road to reflexive comments on the band’s legacy, and serve to underscore the notion that talented creatives are not necessarily, by virtue of their artistic brilliance, the best of role models (at one point Helm quashes an unsavory conversation about their interactions with female fans). Likewise, the fact that a smudge of cocaine had to be removed from Young’s nostril in post-production speaks to the rockstar lifestyle that was par for the course during that era. Scorsese, too, has owned up to a heavy cocaine habit that might have propped him up during this busy period of his career. It’s much more than a filmed concert, and, despite its obvious artifice, an organically-textured encapsulation of the fleeting golden age of rock ‘n’ roll. (It also functions as an interesting companion piece to Dylan’s own Renaldo & Clara.)

The ensuing enmity between Robertson (who viewed the show and the film as a legacy-forming project and dressed for the occasion) and his former bandmates (who would have liked to keep touring) fails to dampen the appeal of this intimate and melancholy musical time capsule.