“You don’t look, you see. You don’t hear, you listen. You taste the top of your mouth. Your nose is filled with fumes and death. The veneer of civilization has dropped away.”

As an immersive storytelling device, Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old is impeccable. Foregoing the use of an omniscient narrator, talking heads to contextualize each sequence, battle diagrams, technical information, and even a coherent narrative, the director plunges us headfirst into the day-to-day lives of the British soldiers of the First World War. We are thrown quite literally into the trenches of battle along with men and boys as young as fifteen years old. Though a number of the director’s editorial and creative decisions have proven controversial in certain circles, calling into question the overall historical integrity of the project, it would be disingenuous not to remark foremost upon the documentary’s mesmeric quality (much of which stems directly from those very same contentious choices). Indeed, if we assess the project against Jackson’s stated goal—to answer the question “What was it like to be a British soldier on the Western Front?”—I think They Shall Not Grow Old succeeds in a way that textbooks and sterile documentaries cannot. Whether that is meritorious or not is a question for the academics, but I can emphatically say that it works as a cinematic experience for someone vaguely interested in the subject matter beyond the requisite grade school curriculum.

They Shall Not Grow Old is unconventional in the sense that it doesn’t work toward a coherent overarching story. Early on in the production process, Jackson made the brilliant decision to let veterans narrate the film in its entirety. Of course, as it was commissioned to coincide with the centennial of the War’s ending, there weren’t any veterans around to interview for it, so the filmmaker was limited to a couple hundred hours of conversations archived by the Imperial War Museum and the BBC.

The film moves through the war in a chronological fashion but never names, let alone follows, a single one of the hundreds of men listed in the end credits, allowing their offhand audio snippets to generate an anonymous amalgam that represents them all. If not intentionally then serendipitously, the universal soldier that emerges from these casually rendered anecdotes conveys a scattered but verisimilitudinous experience, making the viewer extremely aware the soldiers’ proximity and familiarity with death. As the film goes on, these men tell us why they joined the armed forces (often intercut with contemporaneous propaganda), how they were sharpened into fighting shape, how lice and rats and sewage and a stench of death stripped all romantic ideals from their minds, how they were wounded and scared, how they watched battle-forged friends horribly mutilated only feet away from them, how famously they got along with prisoners of war. All of these stories are relayed with an alarming matter-of-factness, as if going to war as a teenager, sustaining oneself on meager rations, and going home to tell your best friend’s mother you watched him die beside you was just the thing to do; neither transformative nor traumatizing, a mere character-building exercise. The audio collage is a truly astounding editorial work that could function as a standalone radio show.

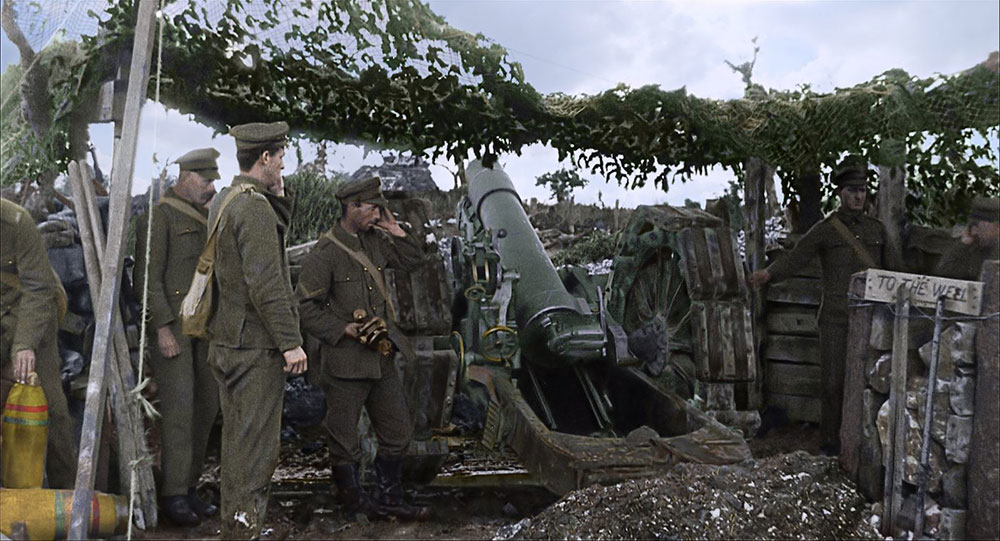

But now we must address the elephant in the room. The big talking point surrounding They Shall Not Grow Old is Jackson’s decision not just to restore the archival footage, but to colorize and re-frame it. And not just to colorize and re-frame, but where necessary, to fundamentally transform it through the use of newfangled technology and painstaking labor. Even purists can pardon the removal of dust, grit, tears, scratches, flickers, splotches. You might even be able to get them on board with color. Indeed, in many cases the footage in all its restored, colorized glory looks astounding. A green tank driving across an impassable trench. Artillery teams working the cannons and stationary guns. The colorization certainly breathes life into footage for audiences unattuned to black-and-white, especially when it comes to the depiction of death. Indeed, images of splattered cranial matter and a bad case of trench foot will linger.

Likewise, the addition of a newly recorded “diegetic” soundtrack (the original footage is silent) adds another layer of immersion, though again this comes at the expense of authenticity. Jackson contracted lip reading experts to pore over his selected footage and in several cases had a voice cast recreate the comments as they’re rendered on screen. In a moment that makes one smile and marvel at how far technology has advanced in a century, one of the soldiers remarks to the camera, “It’s the pictures, mate!” It’s funny to think about, in an era where everyone has a video camera in their pocket, moving pictures were still a novelty in the early 20th century, especially on the battlefield.

All that stuff is mostly very good even if many of the sound additions are based on mere conjecture. But Jackson runs into a problem when he tries to render the archival footage in a modern cinematic language. The root issue is that no one in 1916 had expectations borne of decades of cinematic conditioning. There was no visual language that everyone knew how to speak even if they couldn’t articulate its finer points. But Jackson’s goal is to immerse and thus he knows he needs to speak the language of modern cinema. And so he does a curious but inevitable thing: he zooms in. And, of course, when you zoom in on hundred year old footage, the resolution just isn’t there. Jackson’s solution is to digitally enhance/recreate these faces, and the result is questionable-at-best. Time and again, he takes footage in which a particular face may take up 10% of the screen and blows it up into a closeup, resulting in a horribly mutated, melty, puddly-looking swirl of vaguely humanoid digital chaos. This is compounded when he adds computer-generated frames (to compensate for the 15-16 fps archival footage) and then slows it down into hyper-unreal-slow-motion, causing faces to blur and features to overlap.

Whether this is preferable to grainy black-and-white is debatable, but Jackson emphasizes his enormous contribution by opening and closing the film with the unrestored footage, played sped up and on a smaller frame accompanied by the clatter of a vintage projector. Once the soldiers reach the frontlines, Jackson lops off the top and bottom of the frame and presents his recreation in widescreen. Thankfully, when the time comes to depict the soldiers “going over the top” Jackson resorts to artistic renderings and the veterans’ stories as no footage exists because the cinematographers1 were working with huge clunky tripod-mounted cameras that precluded them from following the men into battle even if they had wanted to risk their lives for the perfect shot. Oddly, he persists in doing his modern zoom-pan across these halftone illustrations.

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old/Age shall not weary them, nor the years contemn.” So reads Laurence Binyon’s poem, ‘For the Fallen’ from which Jackson’s documentary pulls its title. It suggests that the grave sacrifices of the fallen soldiers will be honored by the subsequent generations, by you and me, but also that they will be remembered as they were; for while the survivors grow old and feeble, the fallen remain eternally youthful. In They Shall Not Grow Old (which curiously flips two words to modernize the title, perhaps shifting the meaning more toward the slain soldiers’ bodily demise than their immortal memory), Peter Jackson has indeed brought these men to vibrant life. He has transformed silent symphonies of grey into blooming color; archaic, impossibly distant figures acting out ancient history into living, breathing, talking, laughing, smoking, drinking men existing in a timeless present. It’s an eye-opening evocation of the horrors of war and an immensely informative historical document that one can imagine might become a staple in history classes. And yet, however well-meaning Jackson’s memorial, one can’t help but feel like draping these figures in special effects is somehow improper, that a more reverent middle ground might have been preferable.

1. Much of the footage was originally shot by Geoffrey Malins and J. B. MacDowell for the wartime films The Battle of the Somme (1916) and The Battle of Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks (1917). To my dismay, I don’t think I saw credit given to any filmmaker besides Jackson himself.