“If you try to save wisdom until the world is wise, Father, the world will never have it.”

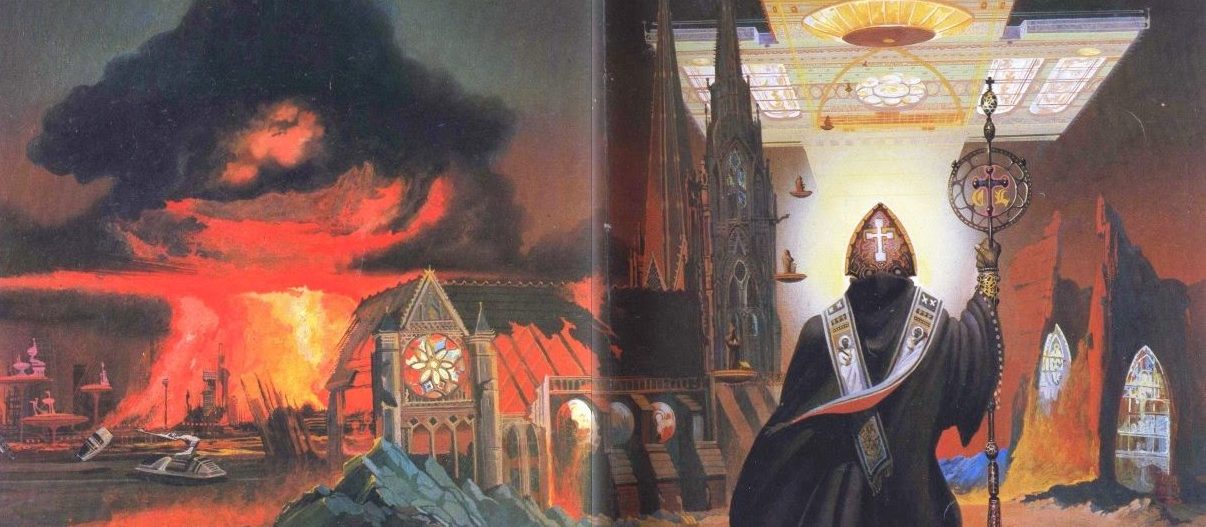

A certain air of mystique surrounds the life and work of sci-fi author Walter M. Miller, Jr. First he was a promising young engineer, then an Army Air Forces radioman and tail gunner, then a PTSD-haunted veteran, then a writer of short stories and television scripts, and finally a depressive recluse who ultimately took his own life. His stories are marked by a fascination with technology and littered with positive allusions to the Judeo-Christian tradition that formed his worldview as a practicing Catholic. After honing his craft for the better part of a decade and writing progressively more complex and thorny stories, he abruptly quit writing at the ripe old age of thirty-six when he released his first novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz. A fix-up of three earlier short stories, Miller’s sole novel-length contribution to the field of science fiction during his lifetime concerns a monastic order founded in the Utah desert in the name of a Jewish engineer who risked his life to preserve mankind’s’ knowledge during an atomic holocaust. It’s an unassailable classic that overshadows all but a few contemporaneous works in the genre and became such a monument that it took Miller the rest of his life intermittently toiling to produce a posthumous sequel (Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman).

Like many futuristic novels, A Canticle for Leibowitz is ambitious in scope. Its three distinct parts sprawl across an entire millennium set hundreds of years in the future, with frequent references to a cataclysmic nuclear apocalypse in the early 1960s that plunged humanity into a dark age. With a post-apocalyptic backdrop, Miller is able to ground his depictions of future human society in a reality that us readers are familiar with, providing a suitable platform for his philosophical ruminations on weighty issues like abortion, euthanasia, the nature of the soul, cyclic history, and church vs. state.

The story of Isaac Edward Leibowitz—electrical engineer, soldier, guardian of knowledge, martyr, beatus, and eventually, canonized saint—is told in fits and starts and woven into the other main tales. With civilization in its death throes in the wake of the nuclear war, survivors begin systematically purging their ranks of any who possess the dangerous knowledge that led to such devastation. In time, the scope of their witch hunt broadens to include any man or woman of learning on the grounds that knowledge of the old ways of life might eventually cause humanity to recreate the evil devices that so recently wrought havoc upon the earth. Seeking refuge from the lethal mobs in a monastic order, Leibowitz commits his life to the preservation of mankind’s accumulated learning through memorizing, copying, and smuggling written works.

Six hundred years later, the abbey of the Albertian Order of Leibowitz juts out of the barren landscape in a remote desert in Utah. The monks who reside there preserve the Memorabilia, but few have the slightest clue what any of it means. To wit, Brother Francis, the young novice who anchors the first portion of the book (Fiat Homo, “Let There Be Man”), spends the majority of his adult life “illuminating” a blueprint of a random mechanical part that Leibowitz had drawn long ago. Despite their lack of understanding, the monks boldly and diligently protect their large store of collected human knowledge through the centuries. In the second part of the novel (Fiat Lux, “Let There Be Light”), as time marches on and the horrors of the past fade into distant memory, a technological renaissance emerges and secular scholars become interested in the contents of the Order’s archives. But the brothers at the abbey are no longer mere preservationists. In fact, when a renowned philosopher of science visits the abbey to study, he finds himself outmatched by a pioneering monk who has created a treadmill-powered dynamo that powers an arc lamp. In the third part (Fiat Voluntas Tua, “Thy Will Be Done”), set several hundred more years into the future, mankind once again possesses dangerous technologies. They have successfully traveled amongst the stars and have started to establish space colonies, but the looming threat of nuclear war imbues each moment with horrible dread.

Have we no choice but to play the Phoenix in an unending sequence of rise and fall? Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, Carthage, Rome, the Empires of Charlemagne and the Turk: Ground to dust and plowed with salt. Spain, France, Britain, America—burned into the oblivion of the centuries. And again and again and again. Are we doomed to it, Lord, chained to the pendulum of our own mad clockwork, helpless to halt its swing?

A Canticle for Leibowitz isn’t dense or thick, but it is impressively provocative. Consider, for instance, that it is the church—specifically the monks who follow in their founder’s footsteps—who preserve ancient scientific knowledge against those who seek to destroy it. Though they cannot understand or employ this vast store of knowledge, they faithfully guard it across centuries. And yet, in a roundabout way, it is precisely this act that allows man to once again sow the seeds of his own destruction.

Though presented as a novel and bearing enough of a resemblance to one that readers won’t balk at it, Canticle is primarily an allegorical work. This is most clearly perceived in the lack of a main character. Leibowitz towers over the entire story, of course, but we only know him through half-remembered stories and the relics that have survived the centuries. Each of the three stories are centered on different characters with distinct personalities, circumstances, and challenges, and in each case they fail to exert control over the world as a conventional hero would. Indeed, man’s powerlessness and incomprehension lies at the heart of Miller’s book. While his three main characters develop a modicum of depth, several side characters function almost entirely symbolically. There is one recurring character, a wandering old Jew who may or may not be the same immortal nomad sauntering through the ages, appears occasionally to ask piercing questions that cause the monks to question their beliefs. There’s a freeloading poet who wears out his welcome during a sojourn at the abbey but then seizes an opportunity to right an injustice at great personal cost. In the last act we are challenged by a nuclear mutant who has grown an extra nonfunctional head and wishes to have “it” baptized.

Most interesting is that there’s not really any villain in the book except for mankind as a collective. Most of the narrative consists of honest, well-meaning men wrestling against the weight of their own consciences. Peripheral politics and technological advances are absorbed and integrated, and arguments feature heavily, but the inner conflicts dominate and essentially boil down to living with the difficult decisions we have to make. Miller’s tone frequently lacks sentiment and is curiously wry, but he alternates between quirky humor and genuine pathos with an impressive fluidity, and carefully laces his pessimistic story arc with an enduring sense of hopefulness.