“In Heaven, everything is fine.”

It would be pretentious to write an off-the-cuff in memoriam for the great David Lynch—the artistic North Star of his generation, a sterling exemplar of the creative life and its ceaseless permutations, a tireless workhorse who reveled in the toil, a bridge between the cinematic margins and the mainstream, a wellspring of inspiration across theme, content, tone, craft, and collaboration, who transported us, however fleetingly, to places both wonderful and strange, introduced us to mysteries without resolution, and prompted us to grow in our awareness of the sublime and bizarre contours of the human experience—when Kyle McLaughlin and Laura Dern’s touching tributes exist, and when the man himself often intimated that adaptations and commentaries seldom capture the true essence of the thing they describe, meaning that my own feelings on his passing yesterday at the age of 78 are something that I cannot fully share with other people. Even my wife, who probably understands me more than any other human being, and knows who David Lynch is, and of my affection for his work, and even enjoys some of it herself, can’t understand why the death of a person I’ve never met can suck the wind out of my sails. Instead, I’ve hastily and sorrowfully edited a review of his first feature length film, that I had written a few months ago, to reflect the past tense, then reversed the changes, having remembered that it is commonplace to refer to great departed artists as if they are still vital creative forces in our ongoing lives and culture (because they are). I’ve no idea if the recent LA wildfires had anything to do with his passing—he was a heavy smoker and had been diagnosed with emphysema—but the city in which he often worked and based his work burning to the ground around him in his final moments seems symbolically appropriate; like his own extinguishing flame burned up his little pocket of the universe. “Ideas are like fish,” Lynch once wrote. “If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper. Down deep, the fish are more powerful and more pure. They’re huge and abstract. And they’re very beautiful.” To have watched David Lynch instinctively casting his line and fiddling around where the big fish were lurking has been a deep, abiding, enlightening experience that has emboldened me to seek out deeper waters for myself. To quote another creative powerhouse totally out of context, “So long, and thanks for all the fish.”

Many brave souls bounce off of Eraserhead like a rubber ball. When I first saw it, long ago, I was intrigued enough to move forward through David Lynch’s oeuvre, which was an immensely rewarding and formative experience—but mostly I didn’t know what to make of it. Now, as a husband and father, it resonates deeply, not least because it is sometimes easier to imagine tending to a sickly worm baby than dealing with my own children’s unique methods of irritation. And, of course, after months of running on three-hour catnaps and coffee, sometimes it does seem possible that a single night’s sleep could be the solution to all of life’s problems.

Nightmarish, surreal, disturbing, grotesque—these are the types of words used to describe Lynch’s debut feature, which was cobbled together over the course of several years as funding allowed and uses its piecemeal nature to enhance its effectiveness. Wildly imaginative in the realms of both storytelling and filmmaking, it conveys a heavily symbolic tale of a young man (Jack Nance) on the verge of adulthood, living in a post-apocalyptic, nuclear hellscape, who has just fathered a “child” and is overcome by the daunting prospects of his future. Thoughts of responsibility, sacrifice, intimacy, fidelity, love, loss, control, self-identity, social isolation, existential helplessness—none of which had previously crossed the young man’s mind—now materialize all at once and fall into his lap in a dreadful heap.

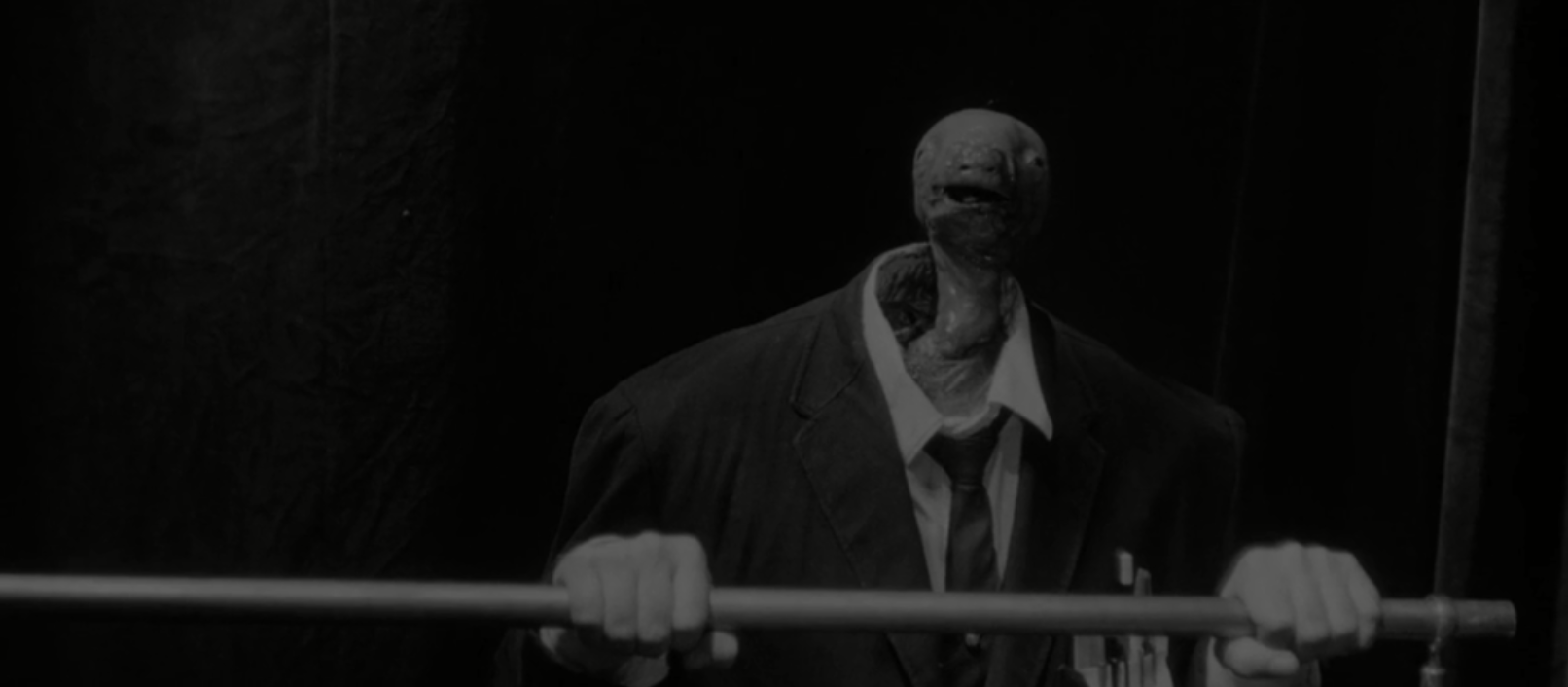

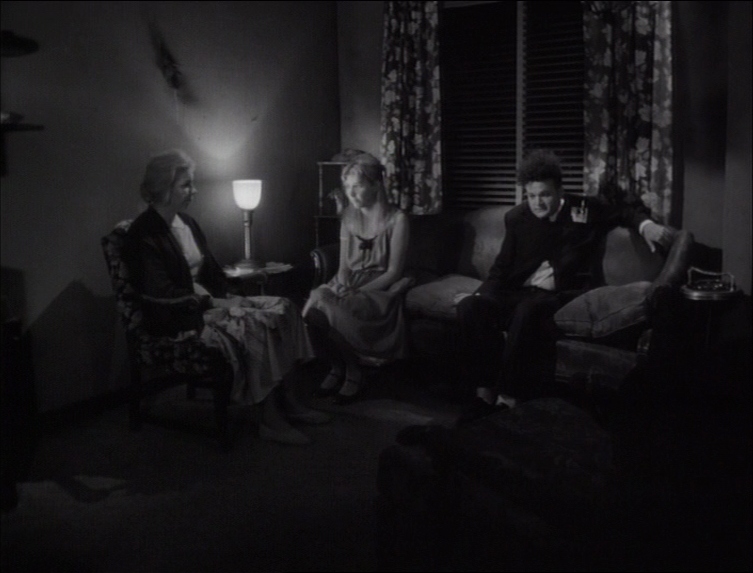

With a vertical shock of hair that matches his face’s expression of permanent alarm and discomfort, Henry is both the projectionist and the audience for a slideshow of terrifying sideshows—scaly men (Jack Fisk) pulling levers in an abstract spiritual realm, deformed singers (Laurel Near) living in the radiator, lascivious women (Jeanne Bates, Judith Anna Roberts), blood-spurting “man-made” chickens, a perpetually mewing, mutant infant, spermatozoa and fetuses everywhere. Some of this is more or less real, or as real as we’re going to get within the film’s context. The chicken, for instance, is carved while Henry has dinner with his epileptic girlfriend (Charlotte Stewart) and her parents (Bates, Allen Joseph).

But as Henry moves through this menacing industrial wasteland and its abstract hinterlands, very little of it ever feels like the mundane world you and I live in. There’s dead vegetation piled up in his apartment, for instance. Each room feels unbearably claustrophobic. There are unusual shadows, desolate streets, uncanny speech, wordless groans, and that weird sort of orgasmic response the mother has when Henry starts divvying up the chicken. And so whenever our focus turns from the surface story of Henry’s care for his necrotic offspring, and drifts into the netherworld of nightmares and twisted memories, the two domains seem organically connected. In a lesser film, we would rightly assume that the Man in the Planet and the Lady in the Radiator are mere metaphors for the id and the subconscious, but that doesn’t feel like the correct approach here at all. The entire film is so thoroughly oneiric that it doesn’t feel right to assume we witness a second of Henry’s waking life, but it also seems wrong to push it all into the realm of dreams. No matter how blurry the distinction, everything that unfolds in Eraserhead has palpable ramifications.

The bridges between these realms are partially constructed from Lynch and Alan Splet’s insidious soundscapes: howling winds, nursing puppies, clunking machinery, incessant buzzes and hisses, creaks and groans, shrieks and squeals, white noise, pipe organ, some of it slowed down or looped to create entirely new and eerie effects. Oftentimes a low-level ambient hum will gradually rise to a staggering crescendo. And of course there’s the cry of that terrible creature, a sound that eventually becomes so overpowering that it consumes Henry’s mind. I’ve seen others point out Lynch’s influence on the development of industrial music (acts like Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV), however, in the back of my mind I’ve always made a connection to the “hauntology” music genre developed by acts like The Caretaker.

My preferred reading of the film at this point is that Henry’s malformed progeny is a dream manifestation of his worst fears, and thus his ultimate solution is not wicked infanticide but a spiritual liberation that he will carry with him into the material world. (There’s an interview clip you can find online where Lynch suggests Eraserhead is his most spiritual film. “Elaborate on that,” the interviewer says. “No, I won’t,” Lynch replies.) His real child, which we never meet, will now have a father who doesn’t view him as an existential burden, but a miraculous part of the human experience. Henry is on the brink of flourishing, not imploding. Of course, such an impossibly hopeful reading is probably too much for such a bleak film to bear and doesn’t account for umpteen other weird things that I haven’t even mentioned, which is why I hesitate to deconstruct it at all. Maybe the pustulent alien baby represents a malnourished creative project or Henry’s inner child or his emasculation or Jesus Christ. Maybe the Lady in the Radiator actually represents death. The film is ambiguous enough for any of these to make some amount of sense. In Catching the Big Fish, Lynch suggests that after he had completed the final cut, he stumbled upon a bible verse that served as the basis for his own interpretation of it—he’s been characteristically tight-lipped about it otherwise. (David Johnson’s guess that it’s 2nd Timothy 1:7 seems plausible.)

For all that, I still mostly don’t know what to make of it all, and indeed prefer it that way. Coming to a place where you feel you’ve exhausted a work of art suggests it has nothing more to say to you, and that’s very rarely the case with Lynch. Lynch is one of the most personal of all filmmakers, alongside Fellini, a consummate artist who works through his most private neuroses for all to see, with no watering down. When making Eraserhead, he was burdened by a complex of frightening thoughts and feelings and decided film was the medium best suited to working those out in an artistic manner. That it doesn’t lend itself to easy analysis on any front suggests it is a pure work of art. It’s one that still disorients me and stirs within me submerged terrors I cannot pin down. It suggests itself as symbolic, but it doesn’t bear the mark of a pretentious artist painfully aware of what his curated imagery would mean to others or even what they meant to him. Rather, this spiderweb of suprarational apparitions feels like it was ripped out of Lynch’s subconscious bit-by-bit and yet fully intact, a wild, earnest grasping for that which remains beyond our reach. What could you remove, what could you add, that wouldn’t diminish the power of its hypnagogic vision?

It didn’t happen overnight, but with Eraserhead, David Lynch went from being an obscure painter and maker of impenetrable underground short films (see The Short Films of David Lynch) to one of the most original voices in American cinema. Looking back at it now with the man’s entire career and sterling reputation to help set expectations, it’s hard to stomach. I struggle to fathom the impact this might have had on viewers fifty years ago, when its closest reference points in cinema, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou and Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet, were themselves nearly a half-century old and not widely known outside of their niche.