“There is beauty which will never be lost; I will preserve it; I am one of those who cherishes it. And I abide. And that, in the final analysis, is all that matters.”

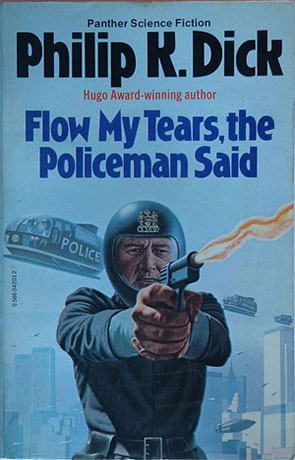

Written in 1970 and released in 1974, Philip K. Dick’s Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said is a near-future dystopian novel that covers a wide range of thematic material in the author’s locomotive, scattershot style. We are treated to existential crises, varying perceptions of reality, genetic engineering, connection of the brain to a computer grid, odd social contracts, the loss of identity, the curse of celebrity, and government-organized mind control. Oh, and drugs. Because PDK was a big fan of them. The story concerns a celebrity who awakes one morning to discover that absolutely no one has ever heard of him; and according to the government records, he doesn’t exist.

Like many of Dick’s novels, he crafts a world that seems odd for oddity’s sake. Within the realm of Flow My Tears, we have the following: a second Civil War occured; the National Guard and the Police Force have instituted a dictatorship, which requires citizens to carry a large number of identification cards to move about in public; the black population has been nearly eradicated via the Sterilization Bill; people fly around in personal aircraft; certain people can read minds; the main character takes advice from the computerized Cheery Charlie (similar to Dr. Smile from The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch); everyone uses drugs, and some of them connect themselves to a group sex computer network; the age of consent is now twelve years old; resistance to the regime comes largely from university students who are literally kept underground; people without ID are sent to forced labor camps; cigarettes are rationed; the police track citizens with microtransmitters lodged under their skin and in their clothing; and sometime in the past half-century a scientist began growing genetically engineered humans called “Sixes” who are supposed to be superior to the average human. Phew.

Dick excels at just casually mentioning this stuff until you figure it out with enough oblique context. Instead of bashing us over the head with all his clever world-building, he just puts us in the heads of a few characters and plunges us right into the central crisis, propelling the readers into the unknown. Jason Taverner is a late-night television host and famous singer whose show regularly attracts thirty million viewers for an hour each week. His records are best-sellers and he can go to bed with any woman he desires. He’s handsome, intelligent, and popular. He’s also misogynistic,1 narcissistic, and drug-addicted, and has woken up to discover that absolutely no one has any recollection of him—including the government, his girlfriend, his lawyer, and his agent. He doesn’t exist.

Finding himself in a seedy hotel with no identity and only a small wad of cash, he doesn’t panic. After all, he’s a Six. Like an entitled celebrity (oh wait, he is an entitled celebrity—an unusual choice of protagonist for PKD), he doesn’t immediately panic. Surely, things will get sorted out and his famous smile will get him through any tough spots. But he soon encounters a world that he never experienced firsthand before. Soon after buying a ride from Eddie, the hotel clerk who is also a mind reader and a police snitch, Jason is set up with Kathy, an ID forger who is also a police snitch. At least Kathy’s status as an informant is for an ostensibly noble cause—her husband is being held at a forced labor camp and her cooperation ensures that he will be returned safely. Except Kathy is neurotic and even though she has been told repeatedly that her husband is dead she still believes she can bring him back if she’s a good informer. She also finds it acceptable to cheat on her husband while he is at the forced labor camp simply because she finds other men “magnetic.”

Taverner then begins to tangle with Felix Buckman, a senior police chief who wishes to maintain the order of things. He has occasional flashes of morality (e.g. he once found a loophole that allowed him to shut down forced labor camps) but he is mostly a scummy character. He is engaged in an incestuous relationship with his sister Alys, who is the first person to recognize Jason since he woke up that fateful morning. When she takes him back to her and her brother’s home, she offers him drugs. She says it’s mescaline, but when he finds her rotting corpse in another room a few moments later, he doubts what is real and what is imagined. He had previously been trying to reestablish himself within the world as he knew it, thinking that perhaps he had hallucinated his entire life as a celebrity. As the novel comes to a close, Dick ties things up in a quick and unsatisfying way (hint: the explanation involves drugs), capped by an indecipherable last chapter and a hasty epilogue.

The story is very readable but also scatterbrained, with way too many one-off characters; some of them are discarded on a whim, others seem to be inconsequential but then end up being important. It’s hard to keep track of what I should even care about while reading. Buckman is an incredibly poorly written character, with a personality that morphs randomly as the story goes on. Unfortunately, that character receives a lot of Dick’s attention. Dick routinely swings for the fences, trying to jam so many disparate ideas into a few hundred pages while barely only having a foggy idea of where the narrative is heading. The result here is an uneven and hard to decipher story that doesn’t seem to have a unifying theme. It features all of his usual concepts and whatnot, but it’s clumsily put together compared to his other works that cover similar thematic territory (Ubik, The Three Stigmata, A Scanner Darkly). It doesn’t help that the author admits he did not really understand the story himself and only later came to believe that he was in some way using the Book of Acts as source material without ever having read it.

If taken at face value as a throwaway PKD meditation on the nature of reality it is fine enough. It’s interesting to consider how our internal world is affected by influences external to it, or the notion that subjective reality can’t be treated objectively. Dick’s novels are always about ideas. Not sentence construction, dialogue, pacing, or narrative cohesion. So take it for what it’s worth. It’s far from his best work and can only be truly enjoyed if you can look past his flaws as a writer.

1. I’m not kidding. At one point, describing a teenage girl who is greeting a forty-two year old man, we are treated to the following masterful prose: “Her friendly nipples jiggled.” Not her breasts—her nipples. And they were friendly.