“The future remains uncertain and so it should, for it is the canvas upon which we paint our desires. Thus always the human condition faces a beautifully empty canvas. We possess only this moment in which to dedicate ourselves continuously to the sacred presence which we share and create.”

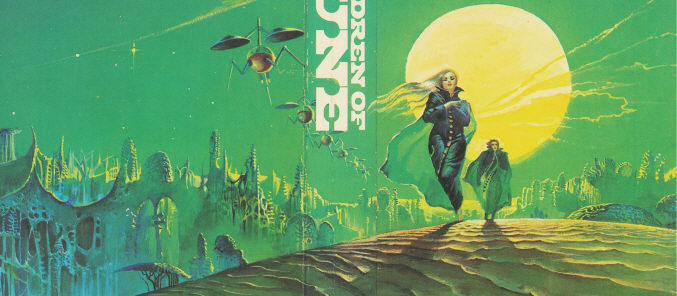

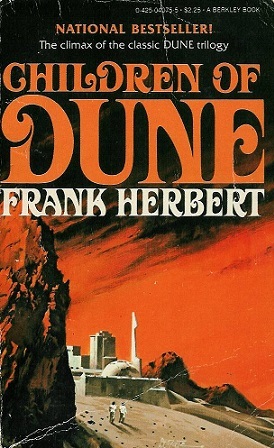

The third book in the Frank Herbert’s Dune saga, Children of Dune, is a good addition to the series, simultaneously wrapping up the original trilogy while expanding the scope of the series for the next installment. Herbert had written parts of both Dune Messiah and Children of Dune alongside Dune, and the three books do feel of a piece, both temporally—the next book in the series, God Emperor of Dune, is set several millennia after the events of its three predecessors—and tonally, as the book is still largely driven by action (though Herbert’s ideas on philosophical, religious, and ideological concepts still permeate every page).

Paul Atreides, the emperor and god of the divided universe, is no longer. Muad’dib still lives on in legend, and a mysterious preacher who may be Paul now wanders the desert speaking words that echo those of the Fremen messiah; but though the Fremen people still worship their fallen god along with multitudes of pilgrims, our lens is now turned primarily toward Paul’s unusual offspring. The preborn twins of Paul and Chani are destined to rule the Empire, but almost no one—including the twins themselves—wants them to ascend to that role. As Ghanima and Leto come of age, the empire is ruled by an advisory council—among them the wise and experienced Fremen leader Stilgar, along with Paul’s wife Irulan, and his sister Alia; however, true power over the empire’s political and religious proceedings lies with the latter, who serves as regent while the children come of age.

Early in the novel, Stilgar, the steady presence of leadership and proponent of a simpler way of life, stands quietly at the bedroom door and watches the sleeping nine year old twins. He realizes now that Paul was not a true god, and, pondering the myriad dissident religious groups he has dealt with in Paul’s name, briefly considers ending the lives of Paul’s offspring in order to return Arrakis and the universe to its simpler way of life. “How simple things were when our Messiah was only a dream,” he thinks. Now, Liet Kynes vision is coming to fruition—grasses are planted to hold shifting dunes in place, homes are built without water seals, and trees populate the landscape. In Dune, when the family arrives on Arrakis and sees trees planted in the plaza, the plants are valued at the number of people that could be sustained with the water that is being used to nourish them; it is an interesting parallel to consider that the lives lost in the holy war were the price paid to bring ecological prosperity to Arrakis. Each group that has come under the ubiquitous authority of the interstellar jihad begun on Arrakis now prays fervently for their own savior; his own people have become undisciplined, and a new generation has grown up without knowing the hardships of Arrakis or the rule of Muad’dib. “If my knife liberated all those people, would they make a messiah of me?”

Amidst rumors that she has rejoined the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, Jessica arrives on Arrakis to meet her grandchildren for the first time, though she first must interact with her daughter, whom she immediately realizes has become possessed, giving in to one of her inner voices—the Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, Alia’s grandfather and mastermind of the first Leto’s death. The twins, possessing the myriad lives of the generations that had come before them, have convinced each other to pursue the Golden Path, the mystical projection perceived by both Paul and Leto through prescient visions that must be followed to prevent the destruction of humanity. In his visions, Leto comes to a conceptual understanding of the history of Arrakis—that it had once been a planet of water, but the introduction of sandtrout had led to the consumption of it in order for the species to morph into sandworms. Consequently, he sees that the absence of sandtrout would lead to the extinction of the worms, and so the spice. And he who controls the spice controls the universe.

The adolescent twins are fascinating characters to read, and allow Herbert to play with some very interesting concepts. They share almost all the same memories, and there is an interesting scene where Leto struggles to explain an experience that Ghanima had not shared with him. Though they fear that they could be overtaken by their inner ancestral lives like they suspect Alia has, Leto is adamant that they once again play their childhood game of allowing Paul and Chani to communicate through them. They confirm that Alia has been possessed by the Baron, and Leto asks if Paul would not take over his consciousness to avoid the risk that the Baron might, but Paul refuses through a strong force of will. But Chani will not let go of her daughter’s consciousness; brutally, Leto verbally assaults his mother, telling her that Paul would hate her if she did not release Ghanima. Leto is interested in learning how others viewed his father; he has all of his father’s memories inside of him, yet he prefers to understand the perspectives of those who knew him. This interest of Leto’s gives rise to questions regarding how we perceive ourselves versus how others perceive us, and which perception is true? The carefully crafted universe, with its incremental and fleshed out differences from ours, acts as a mirror, presenting very human concepts through a mesmerizing display of lofty science fiction ideas.

Meanwhile, Princess Wensicia Corrino, daughter of Shaddam IV (from whom Paul took the galactic throne) and sister of Irulan, prepares her son Farad’n to one day become emperor as she plots to overthrow the Atreides rule through treachery and deception. As the novel goes on, it is revealed that though Wensicia is contemptible, Farad’n is a sensitive young man with many redeeming qualities, and may indeed be fit to rule.

The middle portion of the book is a dense but rewarding maze of assassination attempts, religious fervor, and mythology. Leto fakes his death, and Ghanima puts herself in a mental trance, convincing herself that he has died so that he can seek out Jacurutu without anyone’s knowledge. He is captured and made to undergo the spice trance, but escapes into the desert, undergoing a physical transformation, allowing the small sandtrout to latch onto his hands, and little by little to cover his entire body. The transformation is described in detail both scientifically and metaphysically, but it is hard to follow and obviously not legitimately scientifically accurate. His reappearance makes it clear that he has started down a path of merging his biology with that of a sandworm, as he appears to be some kind of superhero leaping amongst the dunes with ease. Though it comes out of left field, his metamorphosis is fascinating and allows the contrast of Leto’s choice with Paul’s decision to remain human by rejecting the Golden Path. There is an interesting aside during Leto’s journey across the desert: as he bides his time waiting for nightfall, he thinks about the distances between towns near Canterbury, and posits that though the work of St. Thomas Aquinas has been preserved, Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales is likely lost to the sands of time. One of the epigraphs quotes the Orange Catholic Bible (the main religious text of the Dune Universe), using a modified verse from the book of Revelation.

And I beheld another beast coming up out of the sand; and he had two horns like a lamb, but his mouth was fanged and fiery as the dragon and his body shimmered and burned with great heat while it did hiss like the serpent.

There is plenty of plot development that is engaging to read, and contains many of the elements that make the rest of the saga so good, but much of it will become mere footnotes in God Emperor of Dune. After Leto and The Preacher encounter one another in the desert, they return to the capital city to confront Alia. As the superhuman Leto takes control of the throne, several other characters—Alia, The Preacher, Duncan Idaho—meet their deaths. Leto becomes the seemingly immortal God Emperor, and symbolically marries Ghanima. Because he is unable to physically reproduce, he allows her to take Farad’n as a consort in order to continue the Atreides line. Farad’n takes the name Harq al-Ada, which means “Breaking of the Habit”. Farad’n and The Preacher contribute many of the epigraphs at the beginnings of chapters that serve to provide incredible flavor as well as convey Herbert’s ideas in a straightforward manner.

A sophisticated human can become primitive. What this really means is that the human’s way of life changes. Old values change, become linked to the landscape with its plants and animals. This new existence requires a working knowledge of those multiplex and cross-linked events usually referred to as nature. It requires a measure of respect for the inertial power within such natural systems. When a human gains this working knowledge and respect, that is called “being primitive.” The converse, of course, is equally true: the primitive man can become sophisticated, but not without accepting dreadful psychological damage.

—The Leto Commentary, Harq al-Ada

The narrative is set about a decade after Dune Messiah—just as that book was set just over ten years after Dune—and yet the world has changed drastically. Here I think Herbert is deliberately calling attention to how short cultural memory is. In little more than twenty years since Paul ascended the throne, almost everything about the world has changed. Fremen participate in a new religion, are subject to a different form of government, and have become lax in their increasingly water rich world. Contrast this radical shift with something like Lord of the Rings, where it is explained that ages pass before their history fades into legend and then from legend into myth. Like Star Wars, where Jedi are considered a myth only a couple of decades after they are wiped out, Children of Dune draws attention to the scattered nature of human consciousness and collective thought.

Eventually, the mixture of so many new things weighs the book down slightly. The Golden Path remains necessarily vague for the reader, so as to leave the story open for discovery; but the combination of prescience, predestination, and possession, along with the constant philosophizing—which are all interesting to read about in their own right—ends up masking some inadequate plot developments. While Dune and Dune Messiah were pleasurable to read and provoked many unique thoughts, they remained relatively simple to understand. I don’t think I quite grasp the entirety of what Herbert wished to convey with Children of Dune. It is compelling, and as a story it is quite enjoyable; but the ideas of power, social manipulation, and religious fanaticism didn’t always mesh cohesively with the narrative, and the actual narrative developments often take a backseat to the ideas they are meant to impart. But the book’s real power, I think, is not in a plot summary—which can sound juvenile when divorced from the prose—or conversely, in quoting Herbert’s more preachy lines; its influence is in the continued exposure to the world, ideas, and characters. The climax isn’t really the climax, and there isn’t a suitable section of the book to be considered the best. The writing, world-building, character development, and philosophizing all work synergistically to create a fictional world that is simply a joy to immerse oneself in.

Here as with the first book, what really propels this into the upper echelon of science fiction is that many thought-provoking ideas are wrapped within a story that I want to read—all of the edifying elements interwoven to create a beautiful tapestry that is compelling. And yet (barely) beneath the surface lurks a cautionary commentary that the reader is free to ignore or use as a springboard for further investigation of human history and ideas. Though occasionally patchy plotwise, Children of Dune substantially expands the topical, temporal, and spatial scopes of the series, and is on par with the first two novels in its consideration of the past, present, and future of humankind.

I am going to go ahead and bookmark this post for my sister for a research project for school. This is a sweet site by the way. Where did you obtain the design?

Awesome website man, looks very nice.