“Armageddon won’t wait for office hours.”

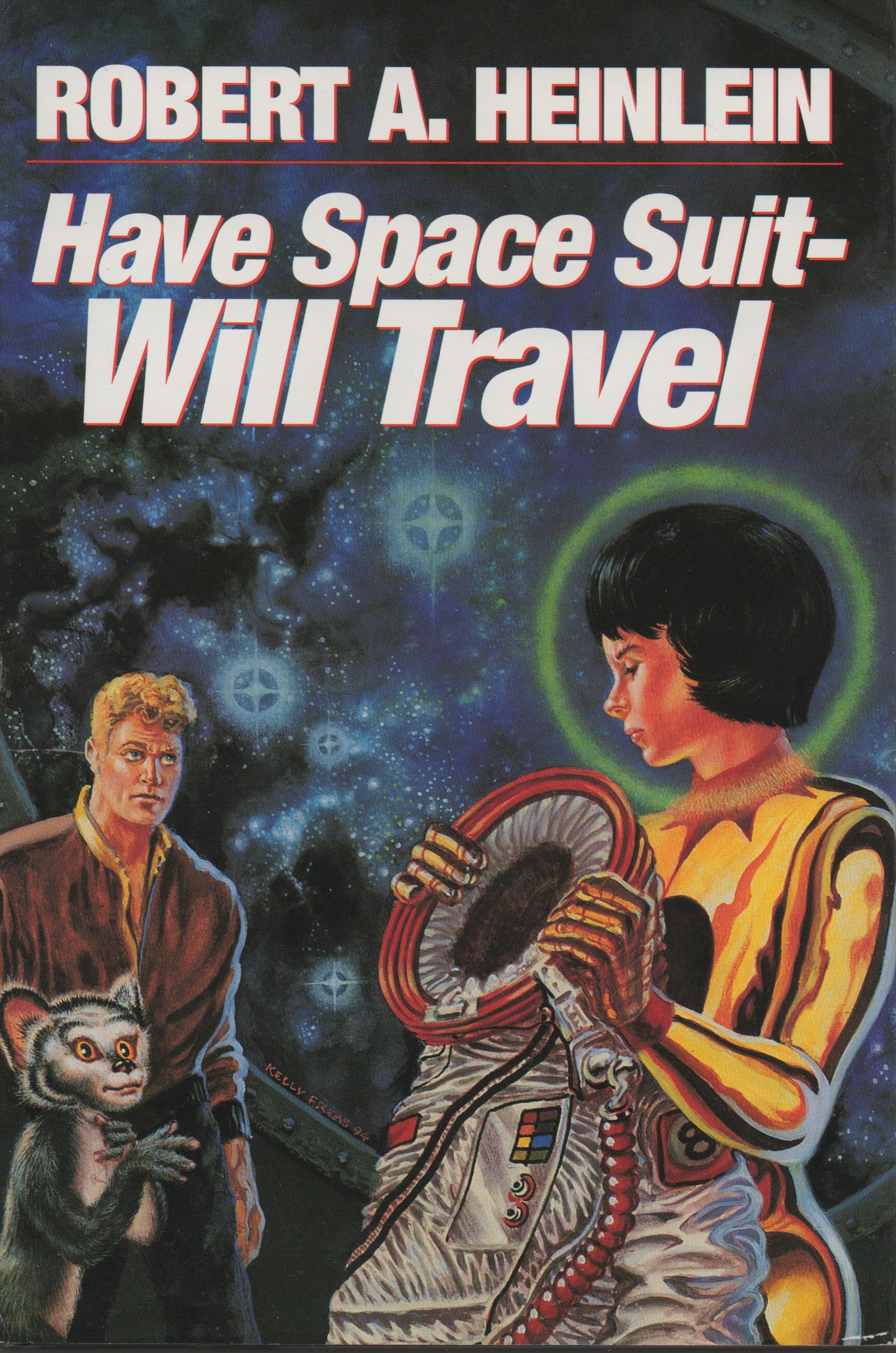

Robert Heinlein’s final juvenile novel for Scribner’s begins with high school senior Clifford “Kip” Russell selling thousands of bars of soap so that he can enter a jingle-writing contest thousands of times with the hope that one of his entries will be selected winner, and that he will be rewarded with a trip to the moon. He doesn’t win, but comes close, and receives a surplus spacesuit as a consolation prize. It ends with Kip and a spunky prepubescent girl named Peewee representing the entire human race in an intergalactic tribunal composed of various alien races, hundreds of thousands of light years away from home. The in-between portion is a fun spacefaring drama, supported by a well-executed hard sci-fi buildup, involving a diabolical race of horrors dubbed Wormfaces and a shapeshifting, nurturing creature who speaks in birdsong, affectionately called the Mother Thing.

Dad says that anyone who can’t use a slide rule is a cultural illiterate and should not be allowed to vote.

Perhaps most importantly, for one interested in Heinlein’s oeuvre after an upbringing sadly devoid of his fiction (my younger self would have loved these “juveniles” even more so than my current self, who uses a chapter or two to drift off to pleasant sleep each night), Have Space Suit—Will Travel is sprinkled with the informational, denunciative, dialectic, and didactic asides that would come to permeate the author’s later work. Some enjoy his early juveniles for their pure stories and despise his later novels for their insufficient plots and unnecessary lengths, while others don’t care for the young adult fare1 and find compensating virtues in his later indulgences. Though I’m only ankle deep in his body of work, I have found plenty to enjoy on both sides of his career divide. This Hugo-nominated novel takes positive elements of each and combines them adroitly, even if it relies on some contrived plotting that the pure storytelling Heinlein wouldn’t have let himself get away with.

Some people insist that ‘mediocre’ is better than ‘best.’ They delight in clipping wings because they themselves can’t fly. They despise brains because they have none.

The story is set in some potential future that looks a whole lot like the 1950s except humans have started colonizing the moon. Once Kip receives his consolatory spacesuit, which he affectionately dubs Oscar, he spends his days tweaking and fine tuning it (or, more appropriately, him, since the pair engage in telepathic conversations quite frequently), adding all of the little gadgets and supplies that real astronauts would have, wearing it around the backwoods—trying his darndest to simulate the experience of exploring the moon. He’s a born tinkerer, and in between his shifts as a soda jerk at the local pharmacy, all he does is spend time with Oscar. One night, while he’s practicing using the radio, he picks up a signal. Next thing he knows, he’s been abducted by a UFO, held prisoner with a fellow earthling: the spitfire preteen genius Peewee. The call he had heard and responded to over the radio was from this precocious eleven year old girl, who had been piloting a commandeered spaceship in an attempt to escape the tentacled Wormfaces along with her solitary ally, the lemur-like alien known as the Mother Thing. No sooner have they landed on the moon—Kip achieving his goal in an unfathomable fashion—then they’re all three taken to a remote Wormface outpost on Pluto, then to Vega.

It sounds kind of silly to draft up a summary paragraph like that, but Heinlein grounds his zany story by walking through some legit scientific explanations in the buildup. The author had been educated in engineering subjects at the Naval Academy and served as a civilian aeronautics engineer during WWII developing pressure suits for high altitude. He spends a good deal of time relaying the technical details of the spacesuit, how it operates, and its limitations. This could easily have become a lumpy dump of exposition, but Heinlein depicts the restoration process from Kip’s explorative viewpoint and makes it feel like a self-contained adventure. This groundedness is gradually eroded as the plot comes to include intergalactic menaces, Neanderthals, and Roman centurions, but it never fades entirely.

“It’s my fault, not yours. I should have looked into this years ago — but I had assumed, simply because you liked to read and were quick at figures and clever with your hands, that you were getting an education.”

“You think I’m not?”

“I know you are not. Son, Centerville High is a delightful place, well equipped, smoothly administered, beautifully kept. Not a ‘blackboard jungle,’ oh, no!—I think you kids love the place. You should. But this—” Dad slapped the curriculum chart angrily. “Twaddle! Beetle tracking! Occupational therapy for morons!”

Although one can extract any number of things from Heinlein’s book, most prominent is his imploration to young people—or anyone, really—to work hard at developing a well-rounded and practical education for themselves. Kip gets himself through many tricky situations by relying on things he had already learned in other, less dire, contexts, or by confidently utilizing tools he is familiar with. Of course, he is comfortable in these situations because his father mentored him and encouraged his inquisitiveness. The catch is that we are culturally discouraged from the kind of self-guided learning that Kip does, as represented by his nemesis Ace Quiggle. (Mr. Charlton, Kip’s boss at the pharmacy idly muses, “I wonder how harmless such people are? To what extent civilization is retarded by the laughing jackasses, the empty-minded belittlers?”)

But of course, the real pull here is a compelling story that involves at least two breathtaking hard sci-fi action sequences. Without that strong narrative pull, Heinlein’s age-worn themes of critical thinking and bootstrapping self-reliance, and his soapbox diatribes against the diluted nature of public school curriculum and our fascination with television, would not have a vehicle to deliver them.

1. Considering the watered down state of education in public schools—institutions that Heinlein takes to task in this very book from 1958!—many of Heinlein’s juveniles would probably be on par with what the middle-of-the-pack high school seniors are reading, if they even crack books open at all.