“The stars winked down their cryptic morse and he had no key to their cipher.”

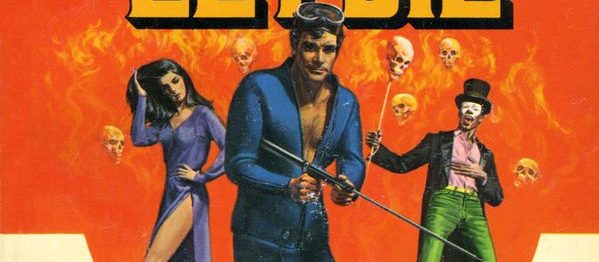

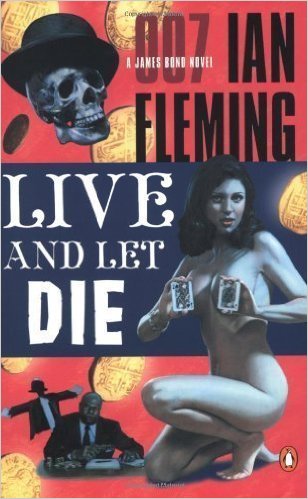

The second James Bond novel follows our hero as he pursues Mr. Big, an agent of SMERSH whose followers believe he is an incarnation of Baron Samedi, the spirit of the dead in the lore of Haitian voodoo. Based in Harlem, Mr. Big uses his power to coordinate a massive smuggling operation moving illicit gold coins throughout the United States. The book was adapted to the screen in 1973; although the film version of Live and Let Die remains fairly faithful to the source material (relative to other Bond adaptations), several of the plot elements that are not used here resurface in other Bond films.

Formulaically, the story starts similarly enough to Casino Royale, with a briefing from 007’s boss M. as a convenient way to dump a bunch of contextual information onto the reader that gives some backstory relating to the investigation and will add some depth later on; though Live and Let Die is closer to the formula that will be used again and again throughout the series. Known as the Fleming Sweep, the technique involves ending each chapter on some kind of cliffhanger, and following a general formula involving Bond, the main villain, and the Bond girl, and how they interact with one another.

As Bond studies for his mission, he reads a book recommended to him by M., called The Traveller’s Tree by Patrick Leigh Fermor, which contains the author’s vivid impressions of a number of Caribbean islands, including Haiti, which is the origin point of the novel’s villain. The text of Fermor’s book describes the voodoo religion of the region; the locals beliefs in zombies, spellcasting, and shapeshifting; and their rituals of dancing, drums, fire, and sacrifice. This was one of my favorite parts of the book, actually, and the style is noticeably different from Fleming’s usual. As it turns out, Fermor’s book is real. It was released in 1950 and details the author’s travels to these regions.

Bond and CIA agent Felix Lieter (returning after his appearance in the first book) arrive in Harlem and head to one of Mr. Big’s nightclubs in order to survey the target and get their bearings. While they are having drinks, a bizarre voodoo-imbued striptease commences, and soon the entire room is shrouded in darkness. Bond and Leiter are snatched from the edge of the crowd. They are interrogated by Mr. Big, and we meet Live and Let Die’s Bond girl, Mr. Big’s psychic prisoner, Solitaire, who is asked to determine whether or not Bond is trustworthy. Bond kills a few men and escapes with a broken finger.

Leiter, on the other hand, fared much better. Before they were abducted from the night club, he had commented to Bond, “I used to be a bit of an aficionado of Harlem. Wrote a few pieces on Dixieland Jazz for the Amsterdam News, one of the local papers. Did a series for the North American Newspaper Alliance on the negro theatre about the time Orson Welles put on his Macbeth with an all-negro cast at the Lafayette. So I know my way about up there.” Fact check—yes, this production actually happened! Orson Welles—of course best known as director of the all-time classic film Citizen Kane—directed what was known as ‘Voodoo MacBeth’ when he was twenty years old. Anyway, when Leiter and Bond meet up again, Leiter’s account of his escape is hilarious.

“They started off by considering all sorts of ingenious things. Wanted to couple me to the compressed-air pump in the garage. Start on the ears and then proceed elsewhere. When no instructions came from The Big Man they got bored and I got to arguing the finer points of Jazz with Blabbermouth, the man with the fancy six-shooter. We got on to Duke Ellington and agreed that we liked our band-leaders to be percussion men, not wind. We agreed the piano or the drums held the band together better than any other solo instrument—Jelly Roll Morton, for instance. Apropos the Duke, I told him the crack about the clarinet—’an ill woodwind that nobody blows good.’ That made him laugh fit to bust. Suddenly we were friends.”

After they prepare to leave that night, Solitaire frantically calls Bond and asks to flee with him. They travel together to Florida via train, but are alerted that Mr. Big has a man on board. They switch trains in the middle of the night, and learn later that their train cabin had been shot up by machine guns after their departure. In St. Petersburg, Bond and Leiter investigate an exotic fish warehouse they think may be part of the smuggling operation. While Bond and Leiter are away, Solitaire is kidnapped.

Leiter returns to the warehouse alone, and Bond later finds his mangled yet still living body in their safe house with a note that says, “He disagreed with something that ate him.” Bond returns to the warehouse by himself, making key discoveries regarding the gold smuggling operation and participating in a deadly shootout, which he (of course) wins.

Bond then heads to Jamaica, where he meets up with John Strangways, head of the MI6 operation there, and is taught to scuba dive by a local fisherman named Quarrel. He makes his way onto Mr. Big’s yacht, where he is reunited with Solitaire and confronts Mr. Big.

There are a few twists that I wasn’t expecting, and Fleming is slightly less grounded than the first book so that the novel is even less believable. Of course, Bond is nearly indestructible, and although he does take quite a bit of damage he is amazingly resilient and pain tolerant.

There are some fleeting contemplations of race, friendship, and evil, but these are not more than cursory. In fact, the intentional considerations of racial tension are undercut by several careless stereotypes, although the scenes in Harlem are do much to convince that Fleming actually knows his subjects, which should lead a modern reader to forgive the more offensive bits due to the obvious interest the author shows in the culture. The novel depicts an outdated yet interesting view on racial differences, which includes strong paternalist, meliorist and eugenicist perspectives.

In a discussion between Bond and Mr. Big, the crime lord explains his listlessness, and his current state of wallowing in the doldrums of routine evil. “Mister Bond, I suffer from boredom. I am prey to what the early Christians called ‘accidie’, the deadly lethargy that envelops those who are sated.” Mr. Big, then, is a perfect opposite of Bond—in the previous book agent Mathis had predicted it was Bond’s destiny to seek out and kill these purely evil men.