“I can tell you the license plate numbers of all six cars outside. I can tell you that our waitress is left-handed and the guy sitting up at the counter weighs two hundred fifteen pounds and knows how to handle himself. I know the best place to look for a gun is the cab or the gray truck outside, and at this altitude, I can run flat out for a half mile before my hands start shaking. Now why would I know that? How can I know that and not know who I am?”

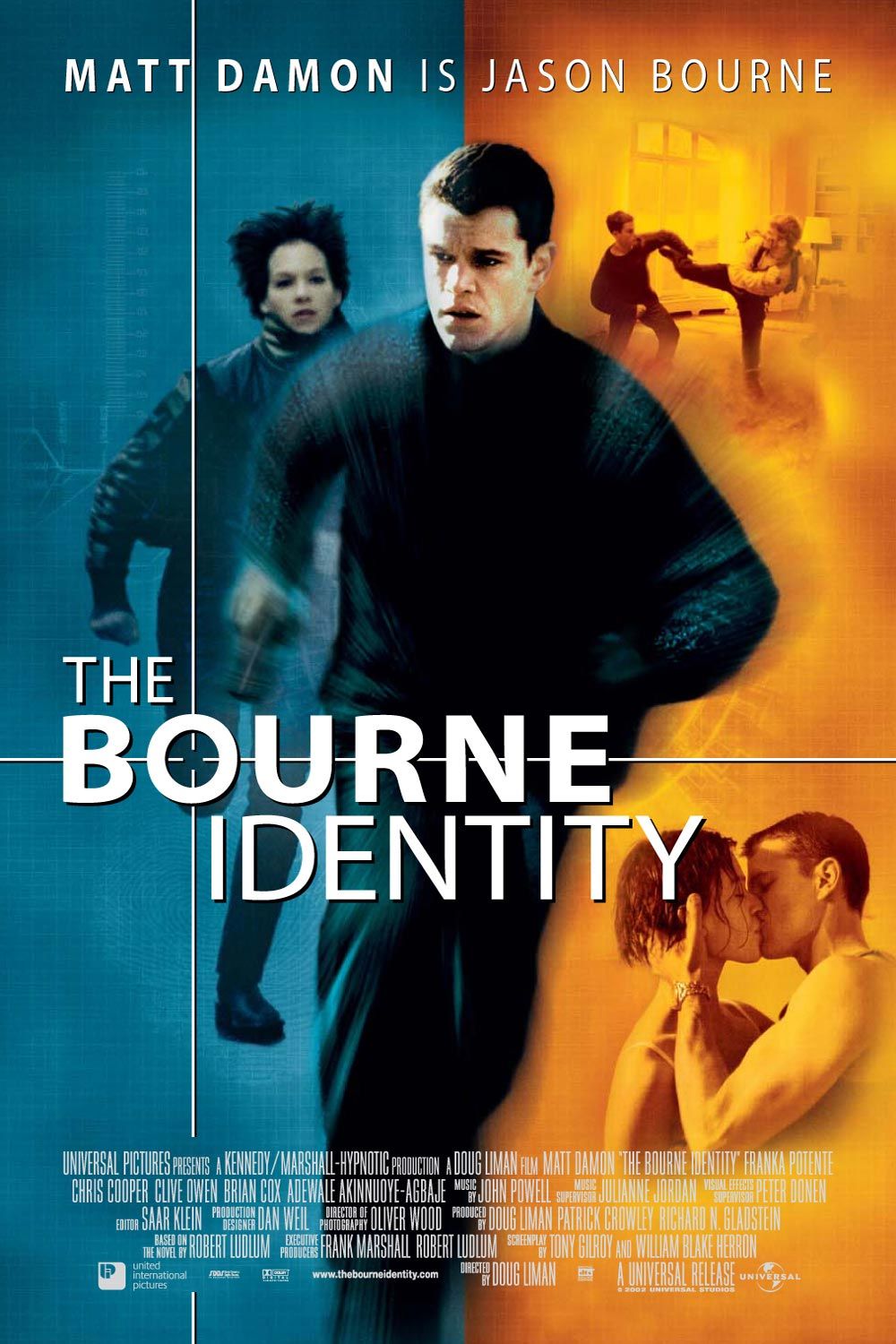

Hitting theaters just as the Pierce Brosnan era of the James Bond franchise was sputtering to a campy conclusion, The Bourne Identity offered a rival secret agent to the movie-going public and solidified Matt Damon as a bona fide action star. Though it presents itself with a passably realistic veneer, whereas Bond was always something of a cartoon, it’s not a serious movie at all. Stripped of the evocative and poignant content present in the source material (which I haven’t read in over a decade), and jettisoning the book’s plot wholesale, it exists solely as a platform for its plentiful action sequences, from fist fights to car chases. Considered solely as a vehicle for hard-hitting choreography, it initially appears solid. There’s some appealing stunt work and a thrilling pursuit through the streets of Paris. But it’s impossible to actually make a judgement here because the difficult editing style (which features a cut every few seconds) attempts to make the audience participants rather than mere spectators, managing to achieve some kind of middle ground between invigorating and nauseating—a balance that would tip further toward the latter once director Doug Liman’s role was taken over by Paul Greengrass for the sequels.

In the middle of the night, as a fishing vessel floats about in the Mediterranean Sea, one of the crewmen spots a lifeless body floating amongst the waves. Dragging him aboard, they quickly discover that what they thought was a corpse is actually a living person, albeit one riddled with bullets and smuggling a small laser device beneath his skin instructing him to seek out a safe deposit box in Zürich, Switzerland. The survivor, of course, is the amnesiac Jason Bourne (Damon). He can remember his skills, from tying knots to fisticuffs to stunt driving; he can fluently speak a handful of languages; he knows his way around the world; but he doesn’t know his name, his occupation, or his home. He doesn’t even know why he was in the Mediterranean Sea, let alone why he had lead slugs lodged in his torso. After earning his keep for a few weeks with the fishing crew and docking in Italy, he must essentially start from square one. But as his skills indicate, he’s a trained killer, and his instincts suggest that he approach every situation with focus and perceptiveness.

We see a flash of his abilities when he’s nearly arrested by the police for sleeping on a park bench,1 as he grabs one of the officer’s batons and knocks both of them out with some slick martial arts maneuvers before fleeing into the snowy night. In the privacy of the Swiss bank, he ascertains that he’s Jason Bourne and/or about twelve other people, each of which is represented on a separate passport within the deposit box along with absurd amounts of cash in various currencies and a handgun. He takes everything but the gun and soon finds himself in a prolonged game of cat and mouse with a CIA black ops program called Treadstone, a shadowy operation to which he may or may not have belonged prior to his amnesia. He pays a random bystander named Marie (Franka Potente) $10k cash to drive him to Paris, roping her into his deadly situation.

As Bourne juggles the double challenge of keeping himself alive and learning who he is, a group of paper pushers in backroom government offices make eliminating him their top priority. An arsenal of hi-tech surveillance instruments are brought into play and a team of incompetent agents and political string-pullers offer several inconsequential breaks from the action by spewing meaningless jargon, slamming phones, and shouting over one another. We’re kept in the dark for a requisite period but eventually it comes out that Bourne failed to assassinate a target for Treadstone, an exiled African dictator named Wombosi (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje). Of course, Wombosi’s still a target, and no sooner has Bourne read the newspaper report of Wombosi’s failed assassination and made the connection than the man is taken out for good by a sniper named “The Professor” (Clive Owen)—another Treadstone operative who, along with two assassins played by Nicky Naude and Russell Levy, are now activated to track down and eliminate Bourne. Chris Cooper portrays Alexander Conklin, Bourne’s former handler and a character who featured prominently in the book trilogy but is unceremoniously killed here on orders from his superior, Ward Abbot (Brian Cox).

Reinforcing the fact that The Bourne Identity is just as disconnected from reality as any old spy thriller, Marie is depicted a shape-shifting caricature—an attractive gypsy dropped in Bourne’s path by chance, somehow unperturbed by the commotion in the embassy which she has witnessed. By turns she is naive, bewildered, trusting, seductive, petrified; a sidekick, a helpless victim, a love interest, etc. Anytime the script needs a clichéd moment, Marie provides it, including a tacked on romantic ending that prompts a roll of the eyes.

As I mentioned, the editing is clearly a problem even though many do not see it as such. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, yada yada whatever—but if there is any beauty in the choreography of the Bourne Identity it is obscured by the rapid cuts and shaky camerawork. There are plenty of sequences that may have been staged with precision, from brutal physical combat to foot and car chases to death-defying stunts, but we’d never know if they actually achieve anything remarkable because the editing chops each sequence into such small pieces that we cannot make anything of it. This style, no matter if it is intentional or necessary, makes the action much less effective than it should have been, but in the process gains a sense of immediacy that conventionally choreographed and lensed action can’t necessarily claim. Some find this jumpy style to be the best thing since sliced bread, but I’m partial to a less hurried aesthetic that emphasizes the spectacle. But it’s not as if Liman is unsuccessful here. Neither is Greengrass in the sequels. Their style works, I just prefer something different. However, that style ushered in by The Bourne Identity and its sequels has become so dominant in the action genre that less skilled filmmakers have rendered many blockbusters nearly unwatchable.

While Bourne may give us a bit more grounding than a typical James Bond entry from that era, it fails to build an engaging plot atop its interesting premise, a blunder all the more shameful because, as my wife (who has read the books within the past month) assures me, the books tell a gripping story with an emotional depth that develops over the course of three novels, an eventuality precluded by key absences and early deaths in this initial adaptation. The Bourne Identity has occasional moments of cleverness and humor, and I wouldn’t consider any part of it outright objectionable, but it certainly underwhelms when compared to its reputation. But for two hours of escapist action, its dearth of visual effects and wintry European setting are satisfactory enough.

1. We must ignore the fact that his secret agent training failed to prevent him from choosing such a prominent and illegal spot to sleep.