“In the morning it was morning and I was still alive.”

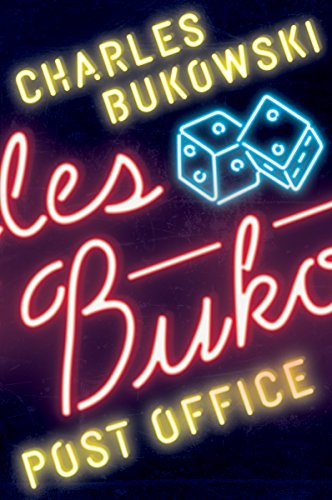

I don’t have a lot to say about Post Office. I think you probably need to be a little bit sick and twisted to really enjoy it. It doesn’t have linguistic flair or complex plotting. What pleasure is to be had is mostly all in the delivery which stems from a mindset that is, well, a little bit sick and twisted. Charles Bukowski’s alter-ego, Henry Chinaski, is an arrogant, beer-swilling, nihilistic, self-destructive womanizer who hates himself and most other people (unless he thinks he can seduce them). The key element that makes Bukowski’s semi-autobiographical novel work is that as the anti-hero and narrator, Henry Chinaski is darkly funny. But that’s basically it. If you find Bukowski’s snide style humorous and enjoyable—and you’ll probably be able to make that call within the first few pages—you’ll like the book. If you don’t, the story itself is barely worth the time spent to read it.

The main strength of the book—aided by the humor—is that the style is conversational to a degree that makes you feel as if you are being told a story rather than reading one. Bukowski’s prose perfectly matches the internal character of Henry Chinaski. He’s a loner and a drifter.1 Throughout the book, Chinaski is employed several different times by the United States Postal Service, putting in long hours in awful conditions, submerging himself in the drudgery and perversely reveling in his misfortunes. He drowns himself in alcohol, smokes relentlessly, and gambles on horse races, moving from one woman to the next with half-hearted resignation.

I went to the bathroom and threw some water on my face, combed my hair. If I could only comb that face, I thought, but I can’t.

The slim book—you could probably read it in one sitting if you really wanted to—utilizes Bukowksi’s own experiences as plot fodder. He really did two different stints at the post office before receiving an offer to quit and write full time. “I have one of two choices–stay in the post office and go crazy…or stay out here and play at writer and starve. I have decided to starve,” he wrote in a letter.

But there isn’t much substance here. It’s an attempt to glorify a destructive lifestyle by portraying it as quaint and romantic. It is funny, sure, but always in a self-deprecating manner. It’s not amusing or comedic—the humor is entirely built around the awful hand fate has dealt the protagonist, such that no matter what else occurs he will inevitably get drunk then go to work hungover the next day. There are depictions of rape and other nastiness that leave a bad taste in my mouth, and Bukowski’s simplistic prose does not enhance the story in a way that would make immoral things pleasant to read about.2 Granted, it was his first novel, written within a month of accepting his gig as a writer. The semi-autobiographical style reminds me of the early work of William S. Burroughs, a little of Jack Kerouac and the other Beats, and the down and out vibe of Henry Miller’s novels (though from what I recall I enjoyed those other works more than Post Office).

I was drawn to all the wrong things: I liked to drink, I was lazy, I didn’t have a god, politics, ideas, ideals. I was settled into nothingness; a kind of non-being, and I accepted it. I didn’t make for an interesting person. I didn’t want to be interesting, it was too hard. What I really wanted was only a soft, hazy space to live in, and to be left alone.

I’m probably not really part of the audience Bukowski was targeting here, so this brief novel simply didn’t really land with me. Part of that is likely its reputation as a classic—a label which it does not seem to deserve—which inevitably leads to certain expectations. You can’t find a diamond in the rough when you already know the critical status of a book. The sardonic tone and humorous anecdotes offer infrequent highlights (enough to keep you moving briskly through the book), and I admire Bukowski’s brutal self-honesty, but I feel like subjecting myself to such an unhealthy individual isn’t really worth whatever other merits may be present. There’s plenty of other hippie/stoner/loner/existentialist/nihilist literature with more substance than this.

1. To my biased internal ear, the tone of the novel is greatly enhanced if you read it in the voice of Tom Waits (whose lyrics often tread the same ground as Bukowski’s writing).

2. In contrast, I read Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita around the same time, and his excellent use of language obscured a series of terrible actions in flowery prose, allowing me to enjoy a story (also told in the first person) focused on a similarly irredeemable character.

Sources:

Dougherty, Jay. “An Introduction to Charles Bukowski”. jaydougherty.com.