“They are gone now. Fled, banished in death or exile, lost, undone. Over the land sun and wind still move to burn and sway the trees, the grasses. No avatar, no scion, no vestige of that people remains. On the lips of the strange race that now dwells there their names are myth, legend, dust.”

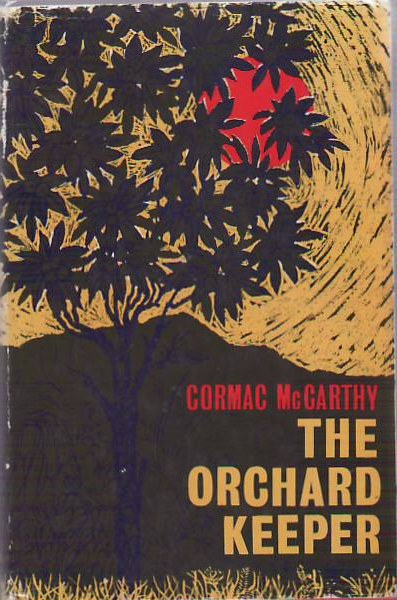

Following in the footsteps of the great Southern gothic modernist William Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy started his career with an ambitious debut, The Orchard Keeper. Already, his prose was fantastic; gritty in detail, creative in structure, delightfully verbose. His grasp of the English language is nearly peerless. If you enjoy Faulkner for his prose, McCarthy’s debut is worth its price for that alone. In the novel, he tells an interwoven tale of an old woodsman, a young boy, and a bootlegger set in Tennessee in between the two World Wars. Though less polished than his later efforts—he is more liable here to get carried away with overly descriptive language that can obscure the factual details of the story—and lacking some of his later trademarks, The Orchard Keeper is a fine start to an illustrious career.

The novel doesn’t convey a connected narrative throughout its entire length; instead, we circle around the lives of its three main characters and witness several small stories nestled into the same vaguely overarching structure. And that’s the biggest problem with the book; despite the beautiful descriptions of nature, grisly accounts of physical altercations, and authentic period details, it is hard to care about the characters when so few important things happen. Compared to his later novels like Blood Meridian, All the Pretty Horses, or No Country for Old Men, his debut just doesn’t have as much meat on its bones and its meandering story left me feeling underwhelmed.

Onto the story, then, which may offer some clarification if the intentional obscurity in the text prevented you from understanding what exactly happened. Marion Sylder, the bootlegger, picks up Kenneth Rattner, the father of the boy, John Wesley. When Kenneth attacks Marion on the side of the road with a tire iron, Marion strangles him, and leaves his dead body in an old chemical spray pit on the property of Arthur Ownby. Ownby, the old man, lives near a rotting apple orchard. He discovers the corpse after some time but covers it up instead of alerting the police.

Marion, who picks up his bootlegged whiskey on Ownby’s property, witnesses Ownby plugging a government installed tank full of shotgun slugs in retaliation at the technological intrusion (a favorite topic of Faulkner’s). As he flees with his whiskey, Marion’s car pops a tire and he wrecks into a creek near where John Wesley is checking his traps. John Wesley helps Marion, and the two become friends, almost like a father and son, unaware of their connection. Marion gives him a puppy and teaches him how to hunt. All three of the central characters become suspects when the police find Marion’s crashed car and the vandalized government tank. When the police approach Ownby’s cabin, he shoots at them with his shotgun and then flees through the woods. Eventually Marion and Arthur are both arrested, and John Wesley leaves town, returning several years later to find it abandoned.

There are frequent digressions throughout. Arthur remembers the legendary painter cats that used to roam the area; there’s the Green Fly Inn that overhangs a valley, and at one point the porch collapses, spilling the visitors onto the valley floor below; the book opens with some men struggling to cut down a tree because it grew around a wrought-iron fence, but the anecdote is apparently unrelated to the rest of the story. All interesting little vignettes that paint a neat picture of the American south in that era, but they don’t add to the story. McCarthy grew up in Tennessee, and the book seems less of a connected story and more of a remembrance of his youth; a memorialization of a bygone era that has since lost its identity to modernization.

Evening. The dead sheathed in the earth’s crust and turning the slow diurnal of the earth’s wheel, at peace with eclipse, asteroid, the dusty novae, their bones brindled with mold and the celled marrow going to frail stone, turning, their fingers laced with root, at one with Tut and Agamemnon, with the seed and the unborn.

It can get a bit frustrating at times when McCarthy repeatedly refers to the main characters as “he” without tipping the reader off to when he has switched characters, and even when he does, Sydler is often just “the man,” Rattner “the boy,” and Ownby “the old man.” This caused me to re-read several sections. Some others I simply went along for the ride hoping that the contextual void would be filled in later. But none of this is surprising considering his primary influence wrote books like The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying. McCarthy’s novel never gets as experimental as those books do; it is more akin to things like Light in August or Go Down, Moses, the only real pretension occuring when he switches from present to past via italics in the middle of a sentence.

In the end, McCarthy’s excellent and wide-ranging use of language creates enough vivid scenes that they’ll bounce around in your subconscious for quite a while. That being said, at times the book can be a downright chore to read, and doesn’t amount to the sum of its parts. Many of the author’s tendencies and predilections are present here—the end of innocence, father-son relationships, the encroachment of technology—and his mimicry of Faulkner is nearly spot-on. But he just never gets there in the way that he does with later efforts like Suttree or Blood Meridian. I wouldn’t recommend starting here, but there’s much to enjoy and ponder.