“The question isn’t indiscreet. But the answer could be.”

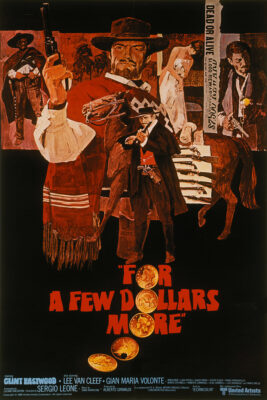

For a Few Dollars More, the oft-overlooked middle film in Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name Trilogy, creates an uneasy alliance between opportunistic bounty hunter Manco (Clint Eastwood) and Colonel Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef), a formidable army veteran who’s turned to the same profession, and perhaps the closest Leone ever came to a morally upright hero. An early staring contest culminates in a show of skill as the two men take turns juggling the other’s hat with consecutive shots from their six-shooters, a scene later echoed after they’ve teamed up when they warn off a bandit posse by shooting apples out of a nearby tree. These episodes highlight Leone’s obsession with the gestures and accouterments of the Western genre in its most masculine form.

As imposing and iconic as Eastwood and Van Cleef are with their menacing squints and quick reflexes—and I’d argue Van Cleef was clearly the better actor at this stage, even if Eastwood is the enduring figure—the picture’s true center of gravity is El Indio (Gian Maria Volonté, who also portrayed a villain in A Fistful of Dollars along with a handful of other actors that appear in both films), a crazed, opium-addicted bandito whose sadistic streak is tied to a harrowing backstory, gradually revealed in harrowing fragments, that lends him an uncomfortable humanity. His gang pulls off an audacious heist, robbing a safe with a sophisticated combination lock that takes some know-how to open. The theft, the getaway, and the safe cracking are all magnificently orchestrated and composed, emblematic of Leone’s penchant for compiling archetypal scenes for maximum stylistic punch, sometimes at the expense of the story’s dramatic minutia.

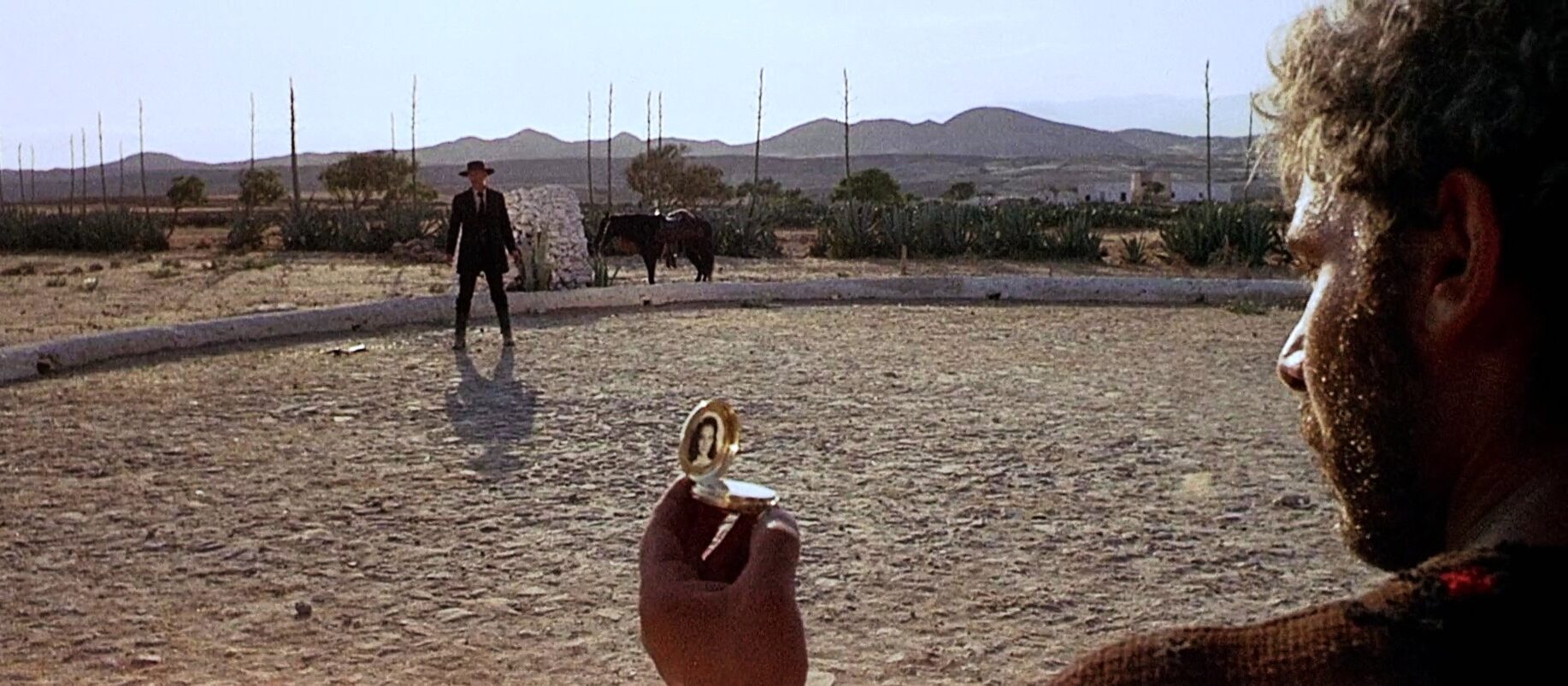

I gladly get sucked into the story every time, but the primary effect of the dramatic elements (the bounty hunters’ tepid pact, the infiltration of Indio’s gang, the honcho’s betrayal of his men) is to manifest a mythic tone and texture rather than simply tell a good story. It initially received some criticism as a mere “bundle of tropes” or however you want to phrase it, but in its severity and simplicity it achieves a stirring sense of stature and mythos. More examples of narratively inessential but tonally crucial details: Manco paying a young local for intel, Mortimer’s Buntline Special fussily fitted with a shoulder stock, the way everyone lights and smokes their cheroots and pipes a little differently, Klaus Kinski’s sneering turn as a hunchbacked sidekick villain, Indio’s grandiose speech from the pulpit of an abandoned church, the soft tinkling of the musical pocketwatch that creates a surreal, hypnotic calm before an eruption of Grand Guignol violence, the wagonload of dead bounties that Manco sets off with at the conclusion. It’s an Italian production made in Spain that includes an American star and a German villain, granted, but this is a pure Wild West fable—there’s no self-aware commentary or postmodern slant, unless one wants to make the case that wanton violence is inherently revisionist after all the white knights of the Hollywood Westerns. Also working to achieve that mythic resonance are the grand vistas, verisimilitudinous tumbleweed towns, abundant extras, balletic shootouts, and another set of aggressive, distinctive motifs from Ennio Morricone. There’s even a train—an unthinkable luxury in the low-budget original.

Ruthlessly condensed to a feverish barrage of classic scenarios pasted together with bare-knuckle style and masculine screen presence, For a Few Dollars More might even be the pinnacle of the loose trilogy, though you’ll not get much argument from me if you choose the rough-and-tumble A Fistful of Dollars or the loose-limbed The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.