“I feel like a whipped dog. Someday I’m going to bite back.”

In the final moments of Paul Schrader’s Affliction, Willem Dafoe offers a poetic summary of the film’s themes of child abuse, generational guilt, crippled manhood, and repressed madness. It has the pleasant ring of Faulkner but is largely unnecessary because the main text does not beat around the bush. “The film is the talking,” as David Lynch says, and this one is not obtuse about what it is saying. In fact, its focus on family dynamics and mental instability is so precise that the irresolution of its catalytic murder-mystery is relegated to a single stanza of the closing narration. Like Taxi Driver and Raging Bull—two Schrader-penned Scorsese productions—Affliction gradually pushes and prods its protagonist until he snaps. Although it’s less satisfying than those undisputed classics, Schrader’s backcountry drama is a solid treatment of familiar ideas and features an astounding performance from its leading man.

Forming bookends with the coda’s narration is an initial voiceover from Dafoe telegraphing the main thread of the story by warning of his brother’s “strange criminal behavior.” Set in New Hampshire, the film begins on a Halloween night so bitter that small-town sheriff Wade Whitehouse (Nick Nolte) must drive snowy streets to shuttle his daughter Jill (Brigid Tierney) to a costume party. As the pair’s conversation quickly illustrates, Wade is a horrible father. Before the night’s done he has left his daughter (who is perhaps eight years old) in a mass of unfamiliar people, smoked a blunt with a buddy while cruising the backroads, and assaulted his ex-wife’s husband. Post-spat, it’s clear to the audience and those around Wade that he should not be Jill’s guardian but he vows that he will win custody and promptly visits his lawyer and seeks solace in the arms of Margie (Sissy Spacek).

It is evident from an early stage that Wade is a poor decision maker, but as the world is filled in around him we begin to realize that these decisions stem from a warped view of his surroundings. And as Schrader is content to present the narrative from Wade’s confined point of view, the audience is left to contend with the feasibility of his assessments. The conspiracy is set in motion when Wade’s friend Jack (Jim True) takes a wealthy businessman on a guided hunting trip and the man suffers a fatal gunshot wound. Jack claims the man slipped and his own firearm discharged, that it was merely a tragedy, but Wade perceives mob involvement, hit-men, covert action. He even suspects his own boss, LaRiviere (Holmes Osborne). He builds up such a collection of circumstantial evidence, hunch, and conjecture that he convinces himself that his boss and his best friend are involved in criminal activity, leading to several explosive confrontations.

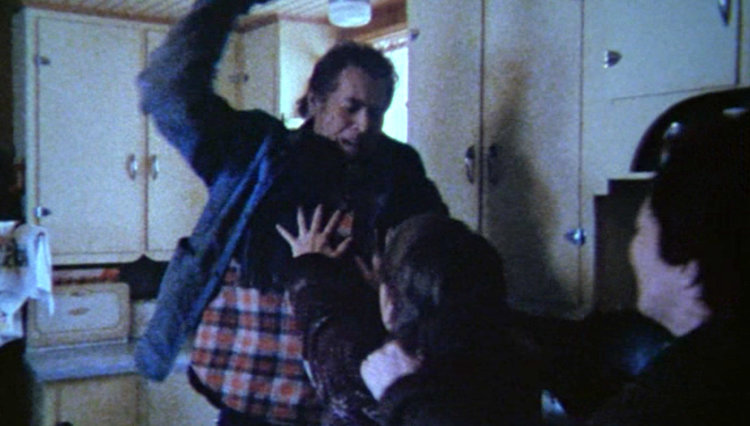

The source of Wade’s mental and emotional instability is uncovered through flashbacks to childhood, captured in shaky 16mm, in which Wade and Rolfe (Dafoe) were regularly in fear for their lives by virtue of living under the roof of a brutalizing father (James Coburn). The deep psychological wounds are opened anew each time Wade visits his parents, who still live in his childhood home. A fresh scar is added to his collection when he finds his mother’s soulless corpse in her bed. Glen Whitehouse, his senses blunted by an unending stream of alcohol, remains undisturbed by the cold, and has let his wife succumb to hypothermia in her own home. It appears that Schrader staged this scene as a long take (unfortunately interrupted once), as Wade tries to wake his mother, realizes the reality of the situation, then wordlessly gestures to Margie and his father who’ve followed him upstairs. After some bewildered mutterings of excuse, sadness, and regret, Glen sits down and continues drinking. For the most part, Schrader tries to remove himself as a director. He hangs back on the periphery and leaves room for his actors to generate the pulse of each scene. But here, and in other instances made startling by their rarity, he punctuates his drama with an intimate close-up.

At the funeral, tensions flare, and Rolfe, on screen for the first time, does nothing but add fuel to the fire of Wade’s conspiracy. Wade and Margie spend more of their time babysitting Glen as the father and son fall back into a wicked pattern of taunting and emotional humiliation. No longer able to numbly shamble through his handful of menial jobs, Wade twists into a chaotic figure bent on his own destruction.

It’s a compelling tapestry of story threads held together by the magnificent performance from Nolte. Nolte has made a career depicting rage, but here, battling his father’s legacy of alcohol and child abuse, that rage is tempered by an aching vulnerability. He’s accepted that he is a lousy husband, father, and enforcer of the law, but it’s the fact that he’s turning into his old man—brawny, detached, drowning in booze and prone to fits of fury—that really tears him up. That and a toothache. Coburn is nearly his equal and won an Academy Award for his work. In Roger Ebert’s review of the film, he offers an anecdote from Schrader. Apparently told that he needed to sink his teeth into the role or else Nolte (a notoriously committed actor) would get on his case, Coburn said, “Oh, you mean you want me to really act? I can do that. I haven’t often been asked to, but I can.”

The true ending of the film has nothing to do with the death of Evan Twombley (Sean McCann) even if a brief montage tries to wrap up its ambiguities. Rather, it confronts the crimes of abuse buried in its distant past head-on. It’s a bleak conclusion without any moral redemption and replaces Wade’s psychological ailments with others that are perhaps even worse. And while I found the frame narration to slightly overstate the film’s themes, it serves a second purpose. In contrast to Wade, who cannot escape the sins of his father, Rolfe has buried his memories so deep that he has erased his own childhood, no longer able to place himself within his own memories. Affliction is a stunningly relentless depiction of emotional trauma rippling across generations.