“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. His hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see.”

Boxing is a sport that I picked up through osmosis. I can’t recall ever sitting down to watch a televised fight until I was an adult, but I must have gleaned the gist of it from montages, video games, and UFC fights. I couldn’t break down techniques or score a round, but I know enough to enjoy it. And I certainly understand the cultural appeal. Like all uber-famous athletes, the top boxers and mixed martial artists are generational talents. But there’s a difference between the fighter and the quarterback, the point guard, and the winger. The difference is that outside of a society where organized sports are commonplace, all of those carefully honed, sport-specific skills wouldn’t mean diddly. Speed and agility will have value in the wild, but compared to a silky smooth jumper or precision passing, the ability to render someone unconscious with your fists is a more desirable skill to possess. I mean, Peyton Manning is one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time, but I think I’d rather have Mike Tyson on my team for the brawl (unless this is a full scale war, then Manning’s tactical skills would be useful, but I digress).

Like golf and swimming and tennis and bowling, boxing is a sport in which the participant has only himself to rely upon during the contest. He can’t defer to a teammate if he’s having an off game, or sit out a match with a sore hamstring. Boxers and other combat athletes must be so finely tuned on fight day that they go months, even years in between fights. If you compare games played/matches fought across sports, it’s kind of mind-boggling. In the NBA you’ve got legendary players who were in the league for 20+ seasons and played upwards of 1500 games. Football, an extremely physical sport, is a little bit more aligned with boxing, with non-kicker/punters topping out around 300 career games. But boxers rarely reach triple digits. Here are some famous names and their total career fights. Jack Johnson—95. Roy Jones Jr.—75. Evander Holyfield—57. Oscar De La Hoya—45. Manny Pacquiao—71. Floyd Mayweather Jr.—50. Muhammad Ali—61.

This low fight count seems to stem from several key issues. Once a fighter enters the upper echelon and becomes a legit contender, they’re going to be competing against other contenders and/or the champ. There’s no “season”—there’s just the fight. And since every title defense is like the Super Bowl, they don’t happen often. This focus around single events requires boxers to dial in their fight style for each specific opponent, which takes time. The high level of competition at the top of the food chain also means that each fight takes a heavier toll on the body—once you’re fighting against the best you’re also getting punched by them. Remember, this is a sport where you score points by injuring the competition. And as Mark Kozelek reminds us on the opening track of Ghosts of the Great Highway—an album saturated with boxing references—although Cassius Clay could dodge punches like a magician, he also got hit a lot (Ali is estimated to have absorbed around 200k blows throughout his career).

In some team sports, positional, skilled athletes can age gracefully—think Stockton, Kareem, Brady, Howe. In non-contact sports, athletes’ primes can last way into middle age—Mickelson, Nicklaus, Clemens, etc. In boxing, the peak is often early, around when you’d expect any athlete to hit their prime, but technical proficiency and a strong chin can extend careers for a long time. Career longevity is also tied to the market. If a fighter is popular, there will always be a venue for him to fight if he wants to fight. For instance, Mike Tyson and Roy Jones Jr.—two retired fighters in their 50s at the time—brought in $80M+ for an exhibition match that fans paid to see largely because of Tyson’s larger-than-life persona. There have been a few boxers to claim titles in their twilight years, but for the most part, legitimate contention is in the cards for only a small arc of a fighter’s career.

Anyway, the reason that I let myself get sidetracked into another dimension thinking about trends and career expectations in boxing is that until I saw Michael Mann’s Ali, I had no idea that Muhammad Ali missed what could be argued was the bulk of his prime. I knew he was born Cassius Clay before converting to Islam; I knew his self-confidence was off the charts and his freestyle poetic trash talk is seen as a precursor to battle rap; I knew he had taken part in events like The Fight of the Century, The Thrilla in Manilla, and The Rumble in the Jungle. When I was growing up, he was almost like a mythical figure for young athletes—“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” the famous poster of The Greatest standing over the KO’d Sonny Liston, etc. Very few of us had ever seen archival footage (and actually, for my generation, our parents would have only been in elementary school when he was active) but everyone knew he was the greatest boxer of all time.

Mann’s film documents his most tumultuous decade, from his surprise TKO of Sonny Liston as a 22 year old in 1964 to his equally surprising reclamation of the heavyweight title from George Foreman in 1974. In between those two events, Cassius Clay becomes Cassius X and then Muhammad Ali as he invests himself in various strands of Islam; his former friend and mentor Malcolm X is assassinated; he protests the Vietnam War, refuses to be drafted, and is arrested and stripped of his boxing license as a result; he goes through a handful of wives; his conviction is overturned by the Supreme Court and he makes a comeback, culminating in The Rumble in the Jungle, the world’s most-watched live broadcast at the time.

Will Smith, who was at that point a huge movie star raking in big bucks, is a revelation as Ali. Trained by Sugar Ray Leonard’s trainer Darrell Foster, Smith nails the physicality of the role. There are four fights that are documented in detail here—both of the Liston fights, Ali’s loss to Joe Frazier, and his defeat of George Foreman to reclaim the belt. That’s a lot of boxing in one movie, and it’s glorious. The combination of Smith’s dedication to sculpting his body and developing convincing boxing skills (the other prominent fighters are played by James Toney, Michael Bentt, and Charles Shufford, all of whom are former boxers), the sense of scale achieved by attempting to recreate the fights punch for punch, and the exceptional lensing by Emmanuel Lubezki create a lively recitation of events. Sports films usually lose much of their potency for me when they try to depict the actual competitions because the performances are just phoned in by non-athletes. Not here. I’ll thrust my neck out a bit and say this is the best depiction of a sport in film.

The drama outside of the ring is also engrossing, even though it’s thrown at us in the form of a rough sketch. The central event is Ali’s refusal to participate in the Vietnam War. After initially receiving 1-Y classification due to his poor writing and spelling skills, the U.S. Armed Forces lowered their standards and made 1-Ys eligible for the draft. Ali tried to claim he was a conscientious objector because military aggression did not align with the teachings of the Qur’an, but the heavyweight champion of the world was arrested, stripped of his boxing license and his title. He stood his ground, despite heavy criticism from the media and a negative public reaction to his draft refusal. He was anti-establishment and he was hated for it, and worse still, he lost his fortune because he couldn’t fight anymore.

And as the film tells it, this was entirely on principle. He was offered a sweetheart deal by the Army, which would have seen him defending his title in no time at all and never sniffing combat, if only he played along. His choice was also not made under pressure from the Nation of Islam, which disapproved of his decision and ostracized him for it. For a massive popular icon, dominant in his field, rolling in money and fame, to put his livelihood and reputation on the line for a deeply held belief—it’s simply unfathomable today. Consider Lebron James, another world-famous, ultrarich, single-name athlete. Rather than use his influence for the betterment of his fellow man (okay, okay, he’s done some good things like start a school, etc.), he bends over backwards to take political stances that are already in vogue, even if that means defending genocide and other atrocities. He’s like an anti-Ali in this regard, lacking in principle and character. And so even though I can’t say I’m in total agreement with the politics of a Muslim such as Ali, I greatly respect the man’s commitment to his beliefs. Even if you disagree with him, you have to admire his nerve and passion.

I ain’t draft dodging. I ain’t burning no flag. And I ain’t running to Canada. I’m staying right here. You want to send me to jail? Fine, you go right ahead. I’ve been in jail for 400 years. I could be there for 4 or 5 more, but I ain’t going no 10,000 miles to help murder and kill other poor people. If I want to die, I’ll die right here, right now, fightin’ you, if I want to die. You my enemy, not no Chinese, no Vietcong, no Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality. Want me to go somewhere and fight for you? You won’t even stand up for me right here in America, for my rights and my religious beliefs. You won’t even stand up for me right here at home.

Elsewhere we see his romantic relationships come and go. His succession of wives are played by Jada Pinkett Smith (Will’s real-life wife), Nona Gaye (daughter of Marvin), and Michael Michelle. His fun encounters with eccentric journalist Howard Cosell (Jon Voight) come up frequently. The sports media personality publicly supported Ali’s name change and his draft refusal, and seems like one of the few people in the boxer’s life who was forthright and honest with him and didn’t try to take advantage. Other prominent figures in Ali’s story that appear include his cornerman Bundini Brown (Jamie Foxx), Malcolm X (Mario Van Peebles), head trainer Angelo Dundee (Ron Silver), promoter Don King (Mykelti Williamson), and his father, Cassius Clay Sr. (Giancarlo Esposito).

Pretty much everyone agrees that the actual boxing is great, that Will Smith looks great, and that his adoption of Ali’s speech patterns, physical mannerisms, and brash public demeanor is great. Criticism is mostly aimed at the film’s noncommittal approach to storytelling. Cultural events happen and we move along without comment, issues remain unaddressed, we jump into and out of key moments without context. It’s like a cliff notes version of Ali’s crazy decade that played out in the public eye. But I think this is only a problem if one expects Ali to be a formulaic biopic. It’s true that with a character as enigmatic as Muhammad Ali—a family man, a womanizer, a religious devotee, a businessman, a folk hero, a trash-talker—a screenplay about his life is bound to find itself running into contradictions and force the writers to compromise in some areas. Even though we’re focused in on a single decade of the man’s life—which leaves out his spoken word album and his Olympic gold medal on one end, and his humanitarian efforts and political activity on the other—the filmmakers still had to choose how to weave a complicated story of sports, politics, and religion around a larger-than-life figure. If there is a failure here, it occurred in the editing room. Michael Mann’s perfectionism is evident in the authentic visuals, from wardrobe to choreography, but the expansive biographical material sometimes leads to awkward pacing, with the film uncertainly lingering in moments that don’t ask for it and skimming over weightier bits because it doesn’t know how to exactly to connect them back into the main narrative.

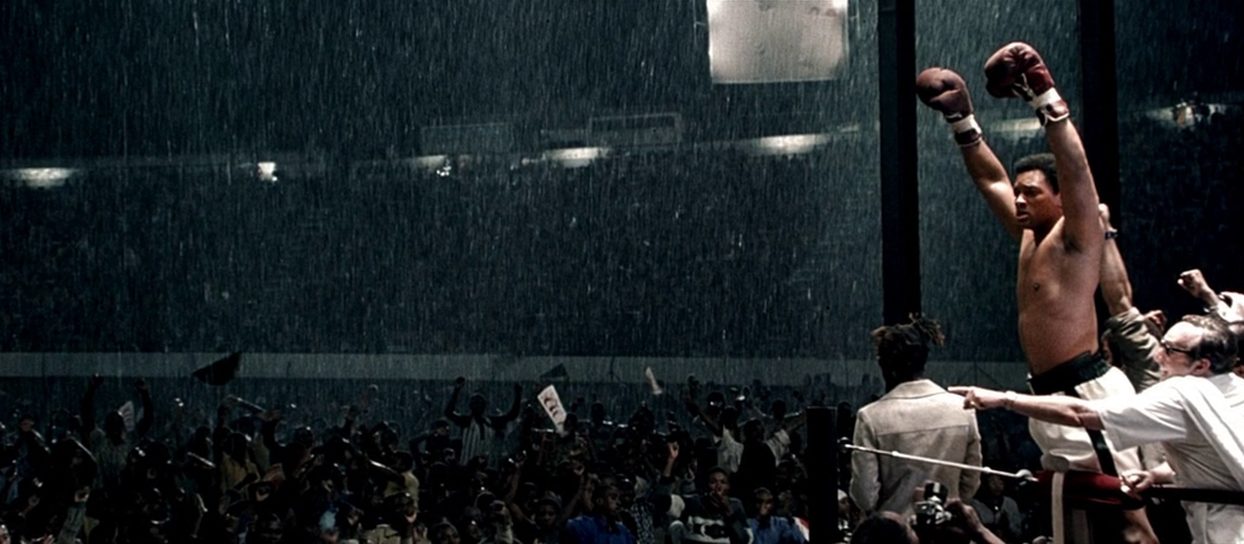

But all of that fades into the background when Ali enters the ring. The climactic Rumble in the Jungle, finally brought to fruition after months spent in Zaire, Africa, is one of my favorite scenes in recent memory. Since I didn’t have a firm grasp on the ins and outs of his career, I could only assume that he won the fight because it was occurring at the end of the film. In this title fight, Ali was facing George Foreman, a much younger, stronger, faster man who was 40-0 in his career. Mann occasionally gives a snippet of inner dialogue, but for the most part, Ali’s rope-a-dope strategy is something we must intuit ourselves. He obviously did not inform his corner of his scheme, as Bundini and Dundee shout profusely and apoplectically at their fighter to get off of the ropes. What we see is former champ, Muhammad Ali, washed up and rusty after three years off, laying on the ropes at the edge of the ring, getting the snot beat out of him by a young bruiser. That’s actually happening, of course, but Ali is counting on the fact that Foreman’s fights typically did not last long. In between rounds seven and eight, the inner monologue plays.

Can’t let you get that second wind which you don’t even know is there for you. You want the title? Want to wear the heavyweight crown? Nose broke, jaw smashed, face busted in. You ready for that? Is that you? Cause you facing a man who will die before he lets you win.

Once the eighth round begins and Sauf Keita’s “Tomorrow” begins to play, you know something is about to happen, but Ali continues to lay on the ropes. Finally, after clinching Foreman one final time, Ali goes on the attack, and Foreman is caught off guard by a flurry of punches that knocks him to the ground, “fallen like a tree in the forest,” as Cosell says. It’s not the most beautiful display of athletic skill, but when it begins to rain on the open air stadium as the champ regains his crown, it’s a genuinely uplifting moment.

I understand why people dislike Ali, but I can’t join them in their criticism. The boxing scenes are worth the price of admission alone, while the only solution to their qualms would be for the film to stretch to five hours or so. The personal and political drama may be undercovered and the excellent cast underutilized, but no individual element here feels out of place. It’s simply a little bit too focused on the overview which leaves some stones only partially turned. Regardless of the critical angle on this one, watching it led me to track down a bunch of archival footage of Ali speaking and boxing, and I’m really grateful for the prompting to flesh out my understanding of the man who christened himself The Greatest. The actual documentary footage of him is probably even more exciting than the movie, but it’s scattered across a million youtube videos and dozens of documentaries. I’ll probably try to track down a few of the latter in the future.

You choose peace or war?