“To thine own self be true. That’s Ron. You see, Ron’s security comes from inside himself. And nothing can ever take it away from him. Ron absolutely refuses to let unimportant things become important.”

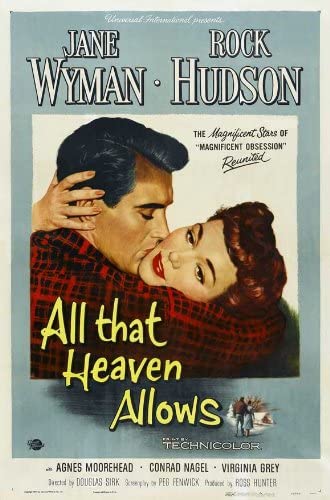

Douglas Sirk’s 1955 film All That Heaven Allows is a melodramatic romance starring Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson. Hudson portrays Ron Kirby, an individualistic landscaper content with his simple life. Jane Wyman is Cary Scott, a rich widow who falls in love with the much younger man who prunes her trees. While on its surface the film can be viewed strictly as a melodrama, and it was specifically marketed toward women upon its release, it has a subtle craftsmanship that is easy to miss but worth scrutinizing.

Initially dismissed as a simple genre piece, a critical reappraisal occurred decades later and All That Heaven Allows is now considered one of the most important films of Sirk’s melodramatic era. On the heels of the successful Magnificent Obsession—which also starred Hudson and Wyman—Sirk was given an increased budget and creative freedom by Universal Studios. Universal was mostly interested in the potential financial gain of a repeat pairing of Hudson and Wyman under the direction of Sirk, but Sirk used the extra funds and freedom to deliver a visually appealing and contemplative film that balances an artful touch with the campiness inherent in melodrama. Using Henry David Thoreau’s Walden as a philosophical touchstone for Ron Kirby’s personal constitution, the film sets about questioning what holds true value.

For the most part, the film doesn’t deviate from the broad strokes of a typical romance formula; the artistry is cleverly woven into the tapestry of what is nominally a genre film. Cary Scott lives a socially dull life, mostly alone; she is the widowed mother of two university students who visit occasionally and she goes to a country club where she spends time with people she dislikes. Her gardener, Ron Kirby, happens to be working at her house on a day that her friend Sara (Agnes Moorehead) must cancel their lunch plans, and so she invites Ron to help her eat the food she had prepared.

He returns later to court her, and the simple love story begins. She is criticized behind her back by her high-class acquaintances. Her children approve of her remarrying, but not to Ron, because he is merely a gardener. Rumors begin that the two had been having an affair while Cary’s husband was still alive. Eventually she is faced with an ultimatum: she must choose the approval of the upper-class society she and her children are accustomed to, or Ron.

Sirk makes generous and creative use of reflections; one scene in particular uses a mirror to symbolize the emotional dilemma Cary faces. As we view Cary’s reflection, there is a knock at the door behind her. Beside the mirror is a vase of koelreuteria (The Golden Rain Tree, which they say will only thrive near a home where there’s love) that Ron had clipped for her earlier in the day. As Cary answers the door to let her children in, they come between her and the Koelreuteria, which represents the wedge they will drive between herself and Ron throughout the film.

There are a few rather clumsy attempts to use the mise en scène to mimic the character arcs and emotions throughout. Ron gradually renovates his house that he intends for Cary to live in, as his “unchangeable” nature gradually evolves. When he proposes, the warm hearth which he has built welcomes Cary, while the wind and snow outside the enormous window represent a life without him. A broken pitcher is emblematic of the couple’s fractured relationship when Cary initially turns down the proposal. There are also several innuendos that I didn’t comprehend as such on my first viewing; they came across as crass when I noticed them, but are inserted in a nonchalant manner that could just as easily be explained away as a misreading, so I’ll give it a pass. But, I mean, come on.

Fortunately, many subtler methods are employed elsewhere to create a deeper cinematic experience. While the film’s critique of materialism and the wealthy’s obsession with class is very blunt and hard to mistake (Cary literally reads from Thoreau’s Walden), it doesn’t try to press the issue through in a ham-fisted scene or two; instead, indicators of the superiority of Ron’s free and independent lifestyle are pervasive throughout the narrative.

In a scene where Cary is discussing her troubles with Sara, a maid is vacuuming the floors in the background. Sara scoffs at the nuisance and closes the door so she does not have to put up with the noise. Contrasted with this, later, is the joyful Alida (Virginia Grey) who eagerly prepares her house for a potluck party that she and her husband Mick (Charles Drake) are hosting. Alida happily hoists sawhorses and wooden planks to assemble a makeshift table so that their tiny house can fit a large number of guests for dinner. While the independent person finds contentment even in mundane work, the pretentious of the upper class find labor—and those who participate in it—beneath them. It is with this perspective that we see Sara cursorily greet Ron Kirby, the gardener, who deserves no more of her attention than the maid.

The potluck dinner is the source of two additional comparison points. First, we have the wine which Ron and Mick bring up from the cellar. The bottles of chianti are roped together, covered in straw, and hanging from the mens’ shoulders. The guests gather around the table as Ron puts on a performance of opening one of the bottles with his teeth. By contrast, Ned Scott (William Reynolds), assuming the role of cocktail mixer after his father’s passing, takes great pride in manning the bar cart. He mixes drinks several times throughout the film; each time, his inclination to do so seems driven by some cultural compulsion instead of any organic impulse. He is merely imitating others who also knew the appropriate time and method for preparing martinis; a child mimicking his father. He finds fulfillment not in the making of the drink, the drinking of the drink, or the giving of the drink; but in the acknowledgment that he has completed the ritual of all of those things.

When Cary first invites Ron to share lunch with her, she presents him with a tray of dainty, perfectly constructed rolls. The rolls are served on a nice wooden tray, and a cloth has been placed on them to preserve their freshness. They are so tiny and intricate that he decides to take two of them to nourish himself. As Cary plies Ron with questions about his work, we see how elaborate her setup had been for a casual lunch with Sara. Meanwhile, at the potluck, some of Mick and Alida’s friends bring an offering of cornbread. It is uncut, still in the pan it was baked in, and draped in a flimsy piece of wax paper. The rolls Cary had prepared (or had had prepared for her) are there to meet some unspoken guidelines of etiquette. Sara was perfectly willing to blow off the casual meal entirely, but had she attended, she would have expected there to be dainty rolls served on a nice tray. The cornbread, while clearly made with care and intention, is almost an afterthought; the real point of the gathering is to eat, drink and be merry in good company. Which, of course, requires food; but not any particular array of choices, and the characters in attendance seem the sort that, had the guests arrived sans cornbread, would have shrugged and welcomed them in regardless.

Another bright spot in All That Heaven Allows is the humorous but narratively significant musings of Cary’s daughter Kay (Gloria Talbott). She has been studying psychology at university, and consistently tries to apply objective reasoning to situations, trying to understand them through the theoretical lens which she has been taught; however, she doesn’t do this in a clinical or academic setting, but as the events are happening in front of her.

As her new boyfriend tries to make an advance toward her, she stops him to explain his psyche to him. “And so you didn’t really want to be a football captain; you wanted love,” she says. Later, when the children meet Ron (not for the first time, but for the first time since Cary announced that she would be married to him) Ned reacts emotionally, accusing his mother of playing a sick joke. There are unwritten rules for this kind of thing, but Ned cannot articulate them. Kay responds: “Ned, I wish you’d treat this whole matter in a more detached fashion. Mr. Kirby, you don’t know mother as we know her. She is really much more conventional than you seem to think she is. She has the innate desire for group approval—which most women have. . .”

Absorbed at a glimpse, the film is easily digestible (or, depending on your taste, perhaps repulsive) as a mere melodrama, but to leave it at that would be a disservice to the artistry and craft buoying the whole thing. Douglas Sirk substantively imbued the film with an individualist philosophy that far outweighs the framework of the basic storyline. Almost every moment is full of intention and the resulting cinematic experience is deceptively eloquent.