“A man has risen to show us that the power is, and always has been, in our hands. We are under siege. He’s showing us that we can resist.”

Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns is usually credited—along with Alan Moore’s Watchmen—for ushering in the gritty aesthetic that has been popular in comics and their silver screen adaptations for the past several decades. That the four-issue limited series had a vast impact on the landscape is neither praise nor criticism (many mediocre pieces of art kickstart dumb trends, and many masterpieces remain obscure), but it is one of those artworks that is both popular and masterful. Miller utilizes the medium of comics such his storytelling seems uniquely suited for the format1 without ever becoming pretentious. It has several elements that are dated now, but the story is still very resonant and relevant.

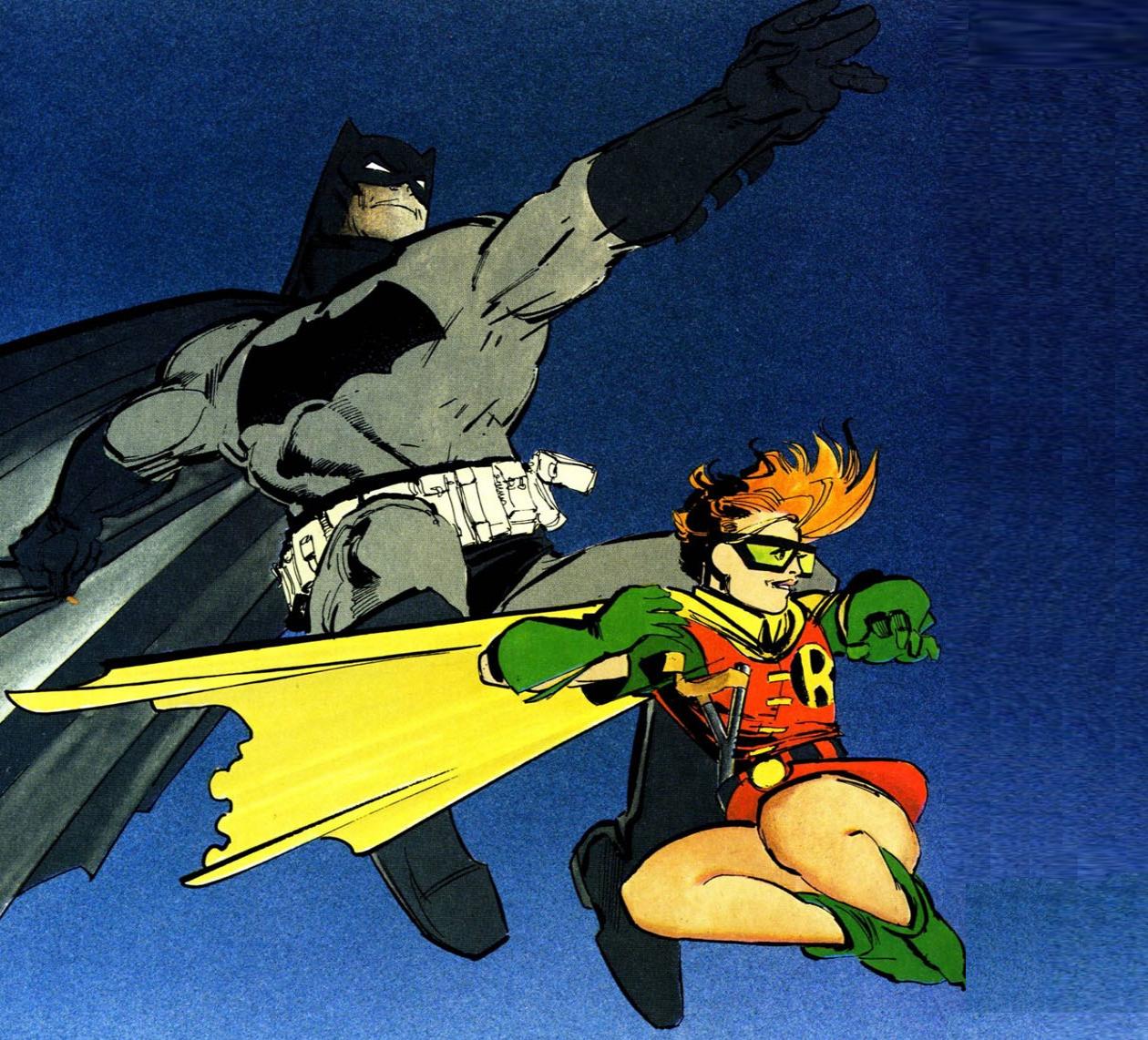

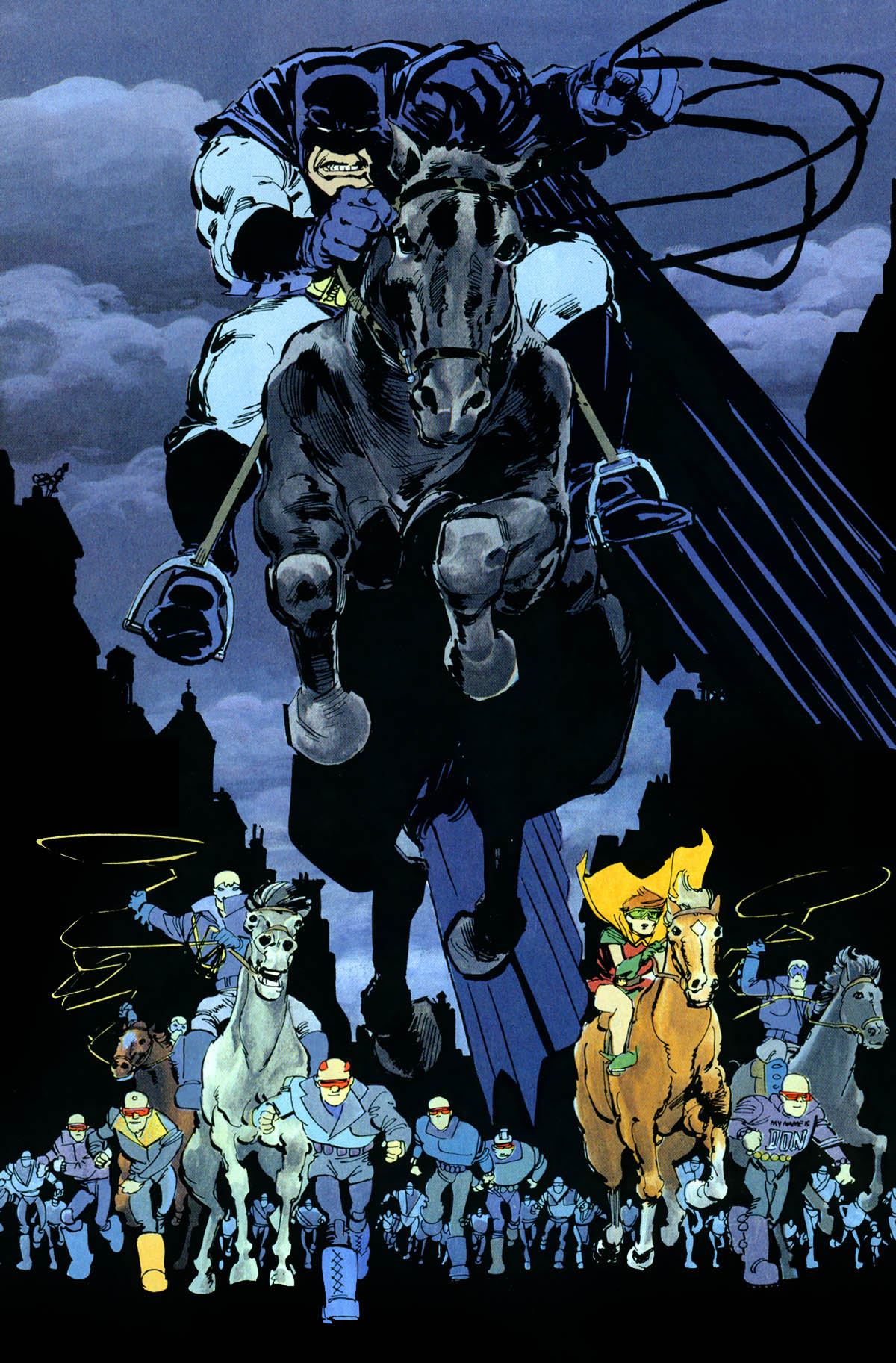

The four issues put us in the shoes of an aging Bruce Wayne coming out of a ten-year retirement to fight for a deteriorating Gotham. Ronald Reagan is President and the Cold War has begun. Superman takes orders from the American government, there is a mutant gang running rampant in the streets, and, though he has aged just as Wayne has, The Joker is as wily and disturbed as ever. Two-Face has been released from prison after cosmetic surgery and psychological rehabilitation, but immediately returns to a life of crime, prompting Bruce Wayne to don his mask once again. At the same time that Batman is plotting his comeback, Commissioner Jim Gordon is forced into retirement, handing over his duties to a younger colleague with whom he has ideological differences. A young woman named Carrie dons the costume of Robin, endearing herself to Batman, who takes her under his wing and learns to rely on her.

The book is thematically heavy. People die, the city streets are patrolled by gangs, and Batman is severely wounded many times. Characters contemplate aging and death. Like the characters of Watchmen, our hero is portrayed as a human being who gets old, loses his touch, and struggles to live up to his own ideals. Mental illness is presented as an incurable disease; you either succumb to it like Batman and Harvey Dent, or revel in it like the Joker. Miller brings Bruce Wayne’s personal trauma to the forefront of the character, which compels him to dedicate his life to stopping crime in a perpetually fruitless effort to calm his soul that still aches from the death of his parents.

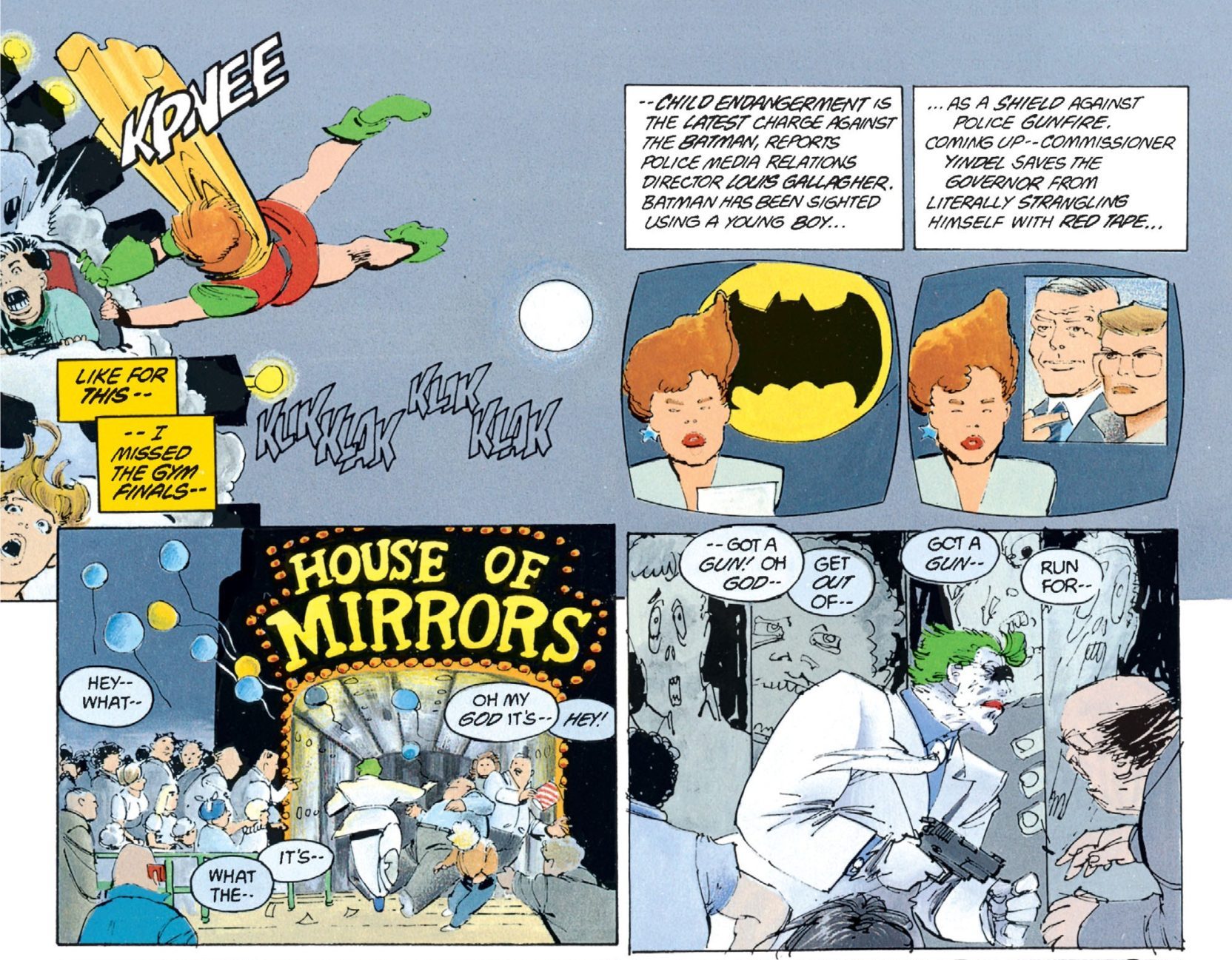

Batman’s return prompts news channels to publicly discuss the merits of having the unauthorized vigilante roaming the streets again, which is one of the key points of tension between Commissioner Gordon and his replacement. The panelling is very creative and does a great job of juggling several storylines at one time. On many pages, two separate stories alternate in various fashions within the confines of a rigid sixteen panel structure while television screens hover on top of the main story and discuss related topics in the guise of newscasts. Miller clearly dislikes news pundits, and these portions of the book are used to provide humor but also to criticize the public news forum for its sensationalism and outright untruthfulness. Thirty years ago this was creative, but it feels almost realistic to see talking heads pop up in the middle of an action scene the way TVs and cell phone screens are everywhere now.

Politically, Miller lashes out both ways, disgustedly spewing venom and warning of a corrupt government that is as likely to promote a criminal in its ranks as it is to put him in jail. This ambiguity is found throughout the entire series. Is Batman a hero or a villain? Is Superman saving the world or has he sold himself to the Americans? Did working himself to the bone ruin Gordon’s relationship with his wife?

Some criticize the text-heavy 16-panel layout that Miller uses because it makes it feel more like a book than a comic. Maybe it is because I’m more used to novels than comics, but I found it to be fine and it transformed these thin volumes into a much larger space in which to explore several key characters in depth. The language Miller uses is colorful without drawing attention to itself, and for the most part characters have distinct voices. Many comics that have followed in the footsteps of The Dark Knight Returns have only been able to grasp the superficial elements that make it compelling—tortured heroes, graphic violence, etc.—but miss the nuance that makes it all work.

The whole series has a unique art style. It’s passably realistic, but occasionally appears very stylized and even exaggerated at times. But the art never feels wrong; the images are used to adequately tell the story. As both author and penciller, Miller’s coordination is excellent. At times, he’ll use an entire page for a large image; sometimes, a series of smaller images make a moving picture; he knows when to zoom in on a character and when to give an overview of the action.

Miller’s series led to a renewed interest in the character of Batman, which in turn gave rise to Tim Burton’s Batman and its sequels as well as Batman: The Animated Series. But it can be argued that the comic was even more influential on Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, its two sequels, The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises, and the connected DC cinematic universe that began with Man of Steel (2013). Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) draws its inspiration partly from the pages of The Dark Knight Returns as well. The unique panel composition, strong dialogue, and personal spin on the Batman mythos provide a singular experience. I can take or leave its violence and most of the political commentary, but it is one of the more engaging comics I have read.

1. The series has been adapted in a two-part feature, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – Part 1 (2012) and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – Part 2 (2013).