“They’re all dead. They just don’t know it yet.”

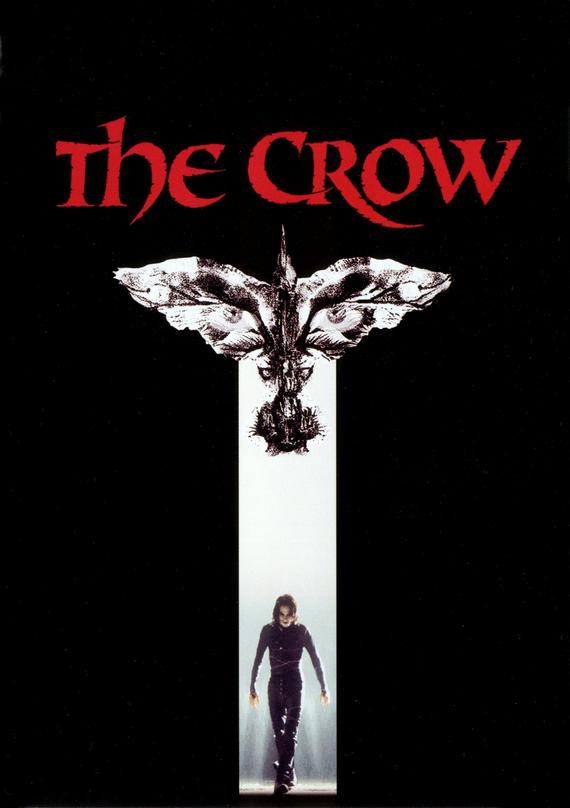

Based on James O’Barr’s 1989 comic book of the same name, The Crow is a macabre revenge tale served up with visual flair, ultraviolence, a gothic rock soundtrack, and a straight-faced delivery of some incredibly cheesy lines. Director Alex Proyas shows off his eye for set design and shot composition while following a pretty straightforward narrative that involves lots of blood and guts.

There’s a huge shadow that hangs over The Crow that must be acknowledged before we get into the contents of the film itself. Lead man Brandon Lee—son of the martial artist and film star Bruce Lee (Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon, Enter the Dragon)—was killed on set near the conclusion of filming. It was a tragedy. He was to be married the week after his untimely death and was probably going to be a charismatic star in the years to come (see the lengthy footnote for some more on Lee’s death and deaths on movie sets in general).1 After the accident, Proyas ditched the entire project, only reconsidering when Lee’s fiancée asked him to finish the film.

Released in the mid 1990s, it was probably the best live-action comic book adaptation at the time. Sure, Superman and its sequels existed, along with a slew of other cheesy Marvel and DC films. Tim Burton’s Batman and Batman Returns had just achieved box office success a in the years leading up to The Crow.2 But for the most part superhero films were still marketed to the same crowd as the comics from which they drew the source material: kids. They were full of cartoon violence, one-dimensional characters, throwaway dialogue and cheap sound effects. But The Crow didn’t even try to be like those films. Now, I’m sure it was appealing to kids—I definitely would have wanted to see it if I was a youngster at the time. Burton’s films both got PG-13 ratings. Mom might have been okay with getting you in to see them. The Crow was rated R “For A Great Amount Of Strong Violence And Language, And For Drug Use And Some Sexuality.”

The story is mostly just a vehicle for cathartic violence. Local musician Eric Draven (Lee) and his fiancée Shelly (Sofia Shinas) were murdered by a group of thugs on “Devil’s Night” a year before the film properly begins. As a voiceover tells us: “People once believed that when someone dies, a crow carries their soul to the land of the dead. But sometimes, something so bad happens that a terrible sadness is carried with it and the soul can’t rest. Then sometimes, just sometimes, the crow can bring that soul back to put the wrong things right.” So a crow visits Eric’s grave and resurrects him from the dead so that he can avenge Shelly’s death (and his own, I guess, but he’s not dead anymore). A fragmented series of flashbacks eventually fills in the details of the original murders as Eric—covered in Joker-esque face paint3—goes on a rampage.

The technical achievements here are outstanding. Grungy and gothic, the set design is reminiscent of Burton’s films but also the grimy future world of Blade Runner (1982). The filmmakers made heavy use of miniatures which are noticeable in the finished product but match its comic-book style, including an opening scene where the city is on fire and a car chase through narrow streets. The use of miniatures would show up again in the director’s next work, Dark City, as well. And of course the choreographed violence is stylish and excessive, with Lee receiving co-credit as fight choreographer.

The soundtrack reads like a who’s who of 1990s alt-rock—The Cure, Stone Temple Pilots, Nine Inch Nails, Rage Against the Machine, Violent Femmes, The Jesus and Mary Chain. The excessive use of music is somewhat integrated into the plot—Eric was formerly a musician and at several points sits on a rooftop meditatively noodling on his electric guitar; and the climactic shootout happens in an office above a concert (featuring My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult) that masks the gunshots—but Eric’s killing spree often times feels like a violent montage.

Part of the reason the story feels shallow4 is that the protagonist’s main source of motivation (Shelly’s murder) happens prior to the start of the film. As a result, during our time with Eric he is basically invincible and just goes around slaughtering people, each murder more gruesome than the last. It’s great fun, super stylish, and has some absolutely cool shots staged by a director with an eye for them (see his debut feature Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds for some superb shot composition). But the appeal is entirely visceral; if you’ve no stomach for artistic gore, you will probably be turned off by the entire thing. For instance, there is a shot where an eyeball is literally fried, and another where a villain is impaled on a gargoyle and his blood gushes out of its mouth.

Aside from our protagonist, several scenes are presented through the eyes of Sarah (Rochelle Davis), a young girl who Eric and Shelly looked after before their deaths, as well as Sergeant Albrecht (Ernie Hudson—Winston Zeddemore in the original Ghostbusters), a beat cop who is confounded when he recognizes the resurrected Eric. While Albrecht’s scenes serve to break up the relentless slaughter, Sarah’s are effectively used to convey emotion and fill out the sparse story. She provides the voiceovers, including the eulogistic closing lines: “If the people we love are stolen from us, the way to have them live on is to never stop loving them. Buildings burn, people die, but real love is forever.” Her scenes give us a passable subplot and some much-needed emotional weight, but I feel that a larger number of flashback scenes with Eric and Shelly would have served the film better to that end.5 The dialogue remains frustratingly trapped with the speech bubbles of comic panels, not even trying to massage it into naturalistic dialogue for cinema. We get direct quotes from Edgar Allen Poe and John Milton, and Eric says things like, “Mother is the name for God on the lips and hearts of all children.” But I digress. It was never intended to be high art—it’s just really good grindhouse cinema.

The Crow has no doubt been elevated in its cult classic status by the specter of Lee’s death. It would have been popular without that for its stylish violence, grimy aesthetic, and gothic soundtrack, but the early demise of its promising young star certainly gives it a certain mystique. Just like Heath Ledger, Kurt Cobain, Tupac, River Phoenix, Elliot Smith and James Dean, the premature death of the artist has the tendency to elevate the reception of their limited output. We never get to see them mature, become jaded, or produce lesser work. Death is an undeniable part of life. That celebrities have their lives immortalized on in movies and music means that receive a perverse amount of attention from the media-saturated culture when death comes unexpectedly. We can retrospectively assess the work of an artist, but there is almost no way to do so without feeling the weight of the life lost. In an uncannily eerie interview given days before he died, Lee paraphrased Paul Bowles’s novel The Sheltering Sky (adapted to the screen in 1990) to capture his thoughts on the shortness of life. “Because we do not know when we will die we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. And yet everything happens only a certain number of times. And a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood—an afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it. Perhaps four, five times more. Perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.”

1. As the story goes, they shot the bulk of the outdoor scenes first, with Lee scantily clad and covered in face paint while rain (artificial and natural) poured down on the set. Filmed on a modest budget, the production was grueling. Overnight shoots taking their toll on the cast and crew, but apparently Lee was one of the few who remained in positive spirits. During the last week of filming they had to shoot a few indoor scenes, including one in which one of the villains shoots a pistol at Lee’s character.

A series of otherwise benign events then occurred that led to a projectile being loaded into the prop gun. First, a prop artist had procured live ammunition while buying props for the set. These rounds were kept in the guy’s car—off set—as they were for personal use (not for the film). Second, in the interest of time, when they realized they had run out of blanks, they modified some of these live bullets into dummy rounds for a scene where a bullet is visible in the gun’s barrel. Third, without anyone noticing, somehow part of a live round remained in the barrel. Two weeks later the same gun was used to fire a blank at Lee. He had a blood squib so no one batted an eye when they saw blood, but they quickly found that he had been shot in the abdomen. He died shortly after reaching the hospital.

There are countless stories of accidents on films sets—Martin Sheen had a heart attack while filming Apocalypse Now, Ed Harris almost drowned while making The Abyss, and nearly every James Bond film seems to have had a mishap—but usually people don’t die. Except that’s not true. It’s just that usually actors don’t die. Stuntmen die; crew members and set designers die; cameramen die. It’s part of the job description for stuntmen, but everyone is out there trying to capture something great that will be immortalized on film and they often take risks to do so. To name a few: stuntman Leonard Joseph Svec died while performing a parachute jump during the filming of The Right Stuff; the production of Resident Evil: The Final Chapter was responsible for the death of crew member Ricardo Cornelius and the plethora of gruesome injuries to stuntwoman Olivia Jackson; second-unit director John Jordan fell out of an airplane and was killed while filming Catch-22; bodybuilding extra George Camilleri suffered a horrific leg injury on the set of Troy that led to a fatal heart attack; cameraman Conway Wickliffe died in a car accident while filming The Dark Knight; stunt pilots Alan D. Purwin and Carlos Berl were killed in an airplane crash during the production of American Made; Stuntwoman Joi “SJ” Harris was killed in a motorcycle crash while filming Deadpool 2; a construction worker dismantling a set on Blade Runner 2049 was accidentally killed; and stuntman Marc Akerstream was killed during the filming of The Crow: Stairway to Heaven, a televisions series based on the film I have become incredibly sidetracked from reviewing.

2. And to be fair, Burton’s first Batman film likely deserve most of the credit (or blame) for beginning the superhero craze, though I’m not sure that either Burton’s film or The Crow—which both spawned series—are the catalyst for the qualitatively uneven, mass-market, connected universe efforts of the 2000s and 2010s.

3. After having seen quite a few portrayals of the character over the years, it is not hard to imagine that Lee would have been superb in the role based on his work here.

4. I believe the story is undeniably shallow. That’s not to say it is not emotional, earnest, or engaging with real-life issues. I know that the author of the comic was inspired by a tragedy in his own life; so I’m willing to grant that it is a coping mechanism for a truly horrific experience. But it’s not very deep.

5. For all I know that could have been part of the plan prior to Lee’s death; so take my criticism here with a large dosage of salt.

Sources:

Owen, Luke. “The tragic story behind the death of Brandon Lee on the set of The Crow”. Flickering Myth. 31 March 2020.

Sellers, Robert. “The strained making of ‘Apocalypse Now’”. The Independent. 24 July 2009.

Boone, Brian. “On-set injuries that ended up in the movie”. Looper. 22 September 2016.

“The Luckiest Green Beret of Vietnam”. Check-Six.com.

Robb, David; Busch, Anita. “‘Resident Evil’ Stuntwoman Injured On Set Out Of Coma – Update”. Deadline. 13 October 2015.

“Crew member crushed to death on Resident Evil: The Final Chapter set”. The Telegraph. 24 December 2015.

Clarke, Roger. “Story of the Scene: You Only Live Twice (1967)”. The Independent. 24 July 2009.

Murano, Grace. “9 Worst Movie Set Disasters”. Oddee. 13 March 2009.

Robb, David. “Safety On Set: Camera Crew Outnumber Stunt Personnel 4-To-1 In On-Set Deaths”. Yahoo. 8 April 2014.

Lincoln, Ross A. “Stunt Pilot Alan D. Purwin, Carlos Berl Identified As 2 Killed in Plane Crash Near Location Of Tom Cruise Film: Update”. Deadline. 12 September 2015.

Patten, Robb, Busch. “‘Deadpool 2’ Stunt Crash Victim ID’d As First African-American Female Pro Road Racer; Director & Fox “Deeply Saddened” – Update”. Deadline. 14 August 2017.

Buncombe, Andrew. “Blade Runner 2: Construction worker killed after set collapses in Hungary”. The Independent. 26 August 2016.

“Crow Curse: Stuntman Killed”. The Hollywood Reporter. 18 August 1998. (Archived).