“My life doesn’t add up. Nothing connects to anything else. I’m not the sum of my parts. All of my parts don’t add up to one me, I guess.”

Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) has concocted a foolproof get-rich-quick scheme: rob his parents’ mom and pop jewelry store. The ~$600k worth of diamonds that the store owns is fully insured, so Charles (Albert Finney) and Nanette (Rosemary Harris) will be reimbursed for the value of the stolen merchandise. Andy and his younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke) will toss the loot to an old fence (Leonard Cimino) and walk away with around $60k each. He thinks it’s a brilliant plan, but things are never quite so simple, are they?

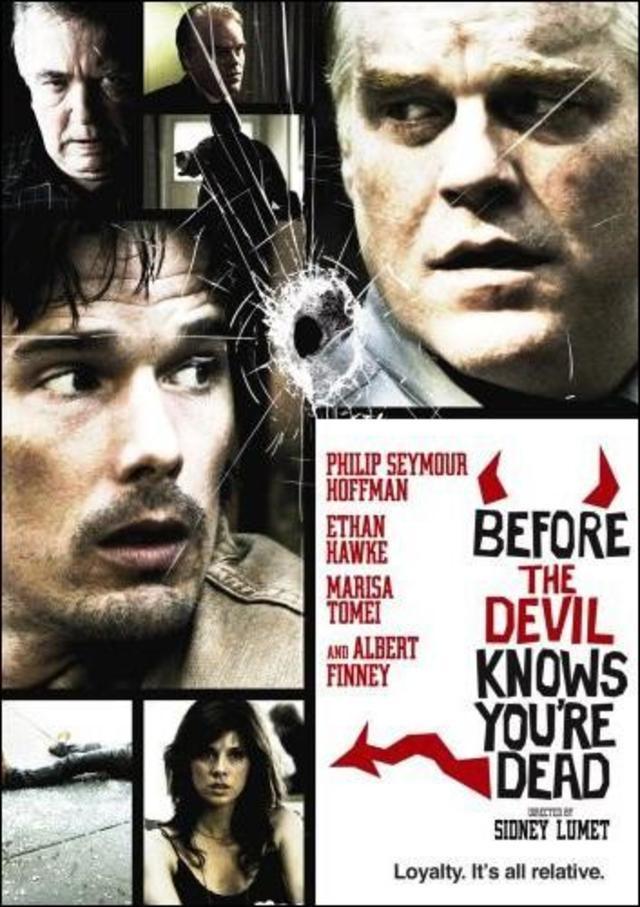

This is the premise of Sidney Lumet’s swan song, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, a depressing, cynical, violent melodrama marked by a towering performance from Philip Seymour Hoffman and solid ones from Hawke, Finney, and Marisa Tomei. Described by one reviewer as “a Greek tragedy with guns,” Lumet’s film, based on a screenplay by Kelly Masterson, conveys its story in distinctly non-linear fashion. Replacing conventional storytelling methods is a creative (if not novel) approach in which the narrative climax occurs early and is then circled in ever-expanding fashion with flashes forward and backward and sideways in order to create context around the event and offer multiple viewpoints. It’s a flamboyant debut for Masterson that offers an audacious vibrancy in the initial scenes even if it becomes a little bit tedious by the film’s end.

The film’s leading man is as fractured beyond recognition as its narrative structure. An embezzling financial executive, addicted to heroin and barely keeping his head above water in a broken marriage, Andy pins all his hopes on ripping off his parents then jetting down to Brazil with Gina (Tomei) to start their lives over again.

The biggest problem with his plan is that he cannot do it all himself. Scratch that, his biggest problem is that Gina is cheating on him with his younger brother, Hank, and has no intention of continuing a life with him. But Andy is unaware of the affair and so enlists Hank, a divorced father willing to scrounge and break the law to provide his daughter with material comforts, to do the bulk of the grunt work. But of course, nothing goes as planned. Hank gets cold feet and hires a ruthless metalhead accomplice (Brían F. O’Byrne) to don a ski mask and carry out the simple robbery in his place. Instead of the regular clerk, whom the boys do not care about, their mother opens the store on the fateful day. Both the accomplice and the boys’ mother lose their lives in the botched heist, even though mom takes a comatose week to succumb to her wounds.

The film is not so much about the personal motivations or decidedly bland details of the planned diamond theft as it is about the emotionally charged aftermath. As Andy’s miscalculations lead to a series of compounding misfortunes, Masterson’s screenplay describes the severe relationship issues that Andy has with his brother and his father. Forced by circumstances into close proximity with both of them, Andy rapidly frays at the seams. His smooth-talking civilized façade is gradually stripped away until all that’s left is a raging manchild full of resentment and shame. Remarkably, Masterson’s script allows these repressed feelings to bubble up and rear their ugly heads even before Charles discovers that his sons were the inadvertent architects of his wife’s murder.

Heist movies typically give their characters strong reasons for turning criminal. That’s not the case here, though, and as it becomes clear that Andy is a true monster, barely even an antihero, we look elsewhere for moral solace. I would hesitate to say that Masterson fails here—rather, I will say that he intentionally chooses not to provide an alternative, preferring to let the audience wallow in the bitterness by deliberately withholding any sympathetic (or even simply smart) characters.

That decision makes Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead too bleak to be enjoyed, per se. Despite the playful structure, there’s really nothing offered in service of levity; no Coen brothers-esque wit to balance the doom and gloom. (The closest we get to something resembling humor is Michael Shannon’s brief turn as the brother of the slain accomplice’s widow, demanding that the brothers pay up to keep them quiet.) Even the environments are drab—dingy shopping malls, grungy apartments, sterile corporate facilities. The picture is so depressing and so well acted that it’s hard to not get dragged down by its mood while writing about it several days after seeing it.

I thoroughly appreciated Masterson’s take on the trendy non-linear narrative. As the scope of the robbery expands, gradually revealing the relationships between characters and adding layers of ethical and emotional considerations, it serves a legitimately exciting function. However, on numerous occasions the “reveal” of a given flashback is trivial at best. It seems that once the decision was made to mix up the order of events, the writer just went all-in regardless of whether or not doing so improved the story in each specific case. This results in several scenes that should have been severely truncated or cut entirely. Such contrivances might be forgiven, but there are also too many needless subplots (Hank trying to get a CD back from the car rental agent, Charles battling with indifferent police investigators) and the ending fizzles out into a predictable anticlimax.

Even still, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead is a compelling, lurid little melodrama acted with gusto; a solid send-off to one of cinema’s master practitioners. If only we all might perform at such a capacity in our eighties.