“The dream is as real to me now as my waking life. I don’t know where one begins and the other ends.”

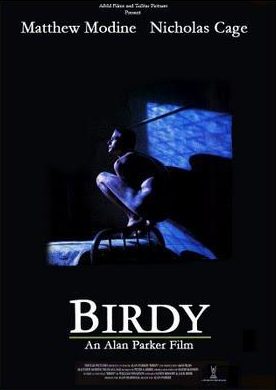

How does a film in which Nicolas Cage dons a full body pigeon costume fly under the radar? I understand that it came out while he was relatively unknown, still acting in small roles and talking in silly accents in his famous uncle’s films. He hadn’t yet risen to superstardom and fallen from grace. He was yet to become the grizzled cult sensation and purveyor of occasionally brilliant schlock that he is today. But even in Birdy—as in Valley Girl and Racing with the Moon—you can see him stretching his wings and beginning to define his signature style. And while he’s become an outrageous black hole over the past couple of decades, here he is completely in sync with his co-star, Matthew Modine. It’s the brilliantly weird performances from these two youngsters that elevate this tale of unlikely friendship and wartime trauma into something tender, offbeat, and haunting.

Birdy was adapted from the book of the same name by William Wharton, a text that was deemed unfilmable by Alan Parker, the man who would eventually sign on to direct. Narrated in first person stream of consciousness by the two leads, their voices delineated by having one of them “speak” in italics, it has a bent toward internal thoughts and flights of fancy that seemed impossible to translate to the screen faithfully. There’s also ambiguity around whether there are two distinct characters or just one. Parker turned the project down, made Fame, Shoot the Moon, and Pink Floyd – The Wall in quick succession, and was enjoying a sabbatical when a screenplay by Sandy Kroopf and Jack Behr landed on his lap. The duo had carefully whittled away and transformed the book by minimizing the inward gaze, giving more prominence to the boys’ friendship and updating the setting from post-WWII to post-Vietnam. With some of the literary hurdles overcome and the wartime trauma made contemporary, the director’s creative juices began flowing and he dove headfirst into the project.

At its core, Birdy speaks of the endurance of brotherly love, strained to its limits when two childhood friends are shipped off to Vietnam and damaged by their experiences in the morally questionable war effort. Al Columbato (Cage) is the victim of a bomb explosion that claims some real estate on his face. His physical suffering is evident (and lent authenticity by Cage’s decision to have two teeth removed sans anesthesia and refusal to have his facial bandages swapped throughout the five weeks of shooting in the hospital). His dear childhood friend, Birdy (Modine)—who had flirted with the notion that he was avian before he was sent overseas—has no physical wounds but is left in a nearly helpless mental state after surviving a helicopter crash. He crams himself in the gaps between his cell furniture and perches on his footboard like a pigeon. A military doctor informs Al that Birdy hasn’t spoken since he was found and then allows him to visit his friend, hopeful that he can prompt a positive change.

Very little time is spent in Vietnam. We don’t even make it there until the movie is almost over. Instead, the frame story at the hospital is prominent, as is the developing friendship between Al and Birdy, which is elucidated with a brilliantly structured series of flashback’s and transitions. There are moments in Birdy where sequential shots move from present reality to fantasy to memory without missing a beat or misleading the viewer. It’s invigorating to watch these beautiful, horrifying, funny, and inspiring vignettes unfold.

The two Philly boys both grew up in poverty and are brought together by the prospect of making money by catching and training homing pigeons. Al is a chiseled playboy, a wrestling champion who likes to show off his six pack and is shown lifting weights at several points. Birdy is an awkward recluse who sits perched in a tree while the other boys play backyard baseball, only performing exercises that will help him achieve flight. They meet when Al’s younger brother mistakenly accuses Birdy of stealing his pocket knife. They become fast, unlikely friends, with Al bemused and mystified by his pal’s abstract obsession with birds, not to mention his disinterest in women.1

There’s nothing in my life to keep me here anymore. I wish I could die and be born again as a bird.

And so we bounce around between the pair’s past adventures, Birdy’s dreams of flying, and a present in which a banged up Al tries to coax his friend back to reality. In the past, they fix up an old beater car, get arrested, cover themselves in pigeon feathers and climb on rooftops, build an aviary, get mixed up with a nasty dogcatcher, and try to rig up a da Vinci–esque flying machine. There’s a great scene where Birdy tries to purchase a canary from an older lady who makes him promise that he will only let the birds have sex like civilized folk. She doesn’t want them engaging in any “Roman orgies.” Later, Birdy names a male canary after Al—pretty weird, right?—but tells him the name is only temporary because he will learn to speak canary and then call the bird by its true name. In this way we gradually come to understand Birdy’s peculiar obsession.

In a bit of a twist, in the present, we get the sense that Dr. Weiss (John Harkins) might be using the boys’ conversations to evaluate Al’s mental wellbeing as well. Indeed, as things play out it becomes clear that Al desperately needs his friend. Possibly more than Birdy needs him. Thankfully, Parker and his team stage most of the scenes as a two-man show. Smaller roles are prominent—Weiss, Al’s father (Sandy Baron), Birdy’s parents (George Buck, Dolores Sage)—but relegated to isolated scenes. This was a wise decision because Cage and Modine are operating at a level beyond their fellow cast members. What’s most remarkable about their roles is how versatile they each must be—Modine goes from a reserved obsessive to a mute birdlike creature, Cage from a brash jock to a desperate husk of a man. Cage’s turn as the shell-shocked veteran is perhaps his most sympathetic performance.

Setting aside the central drama, Birdy is also remarkable for its technical and sonic achievements. In Birdy’s fantasies his imagination takes flight. To achieve this, Parker arranged to be the first director to shoot using the SkyCam, an elaborate system designed by serial innovator Garrett Brown. “We’re the guinea pigs,” Parker said to his producer, Alan Marshall. “Guinea pigs can’t fly,” Marshall replied. Parker had a complex shot all lined up, the camera swooping past a church steeple, over a junkyard, over burned out cars, backyards and baseball fields. Half a square smile was dressed up like it was the 1960s, dozens of extras were choreographed playing sports, walking dogs, pushing strollers, gossiping, driving… but then the SkyCam crashed on the second take and forced some improvisation. It’s a testament to Parker’s creativity that he was able to convincingly rework the centerpiece of his film using an assortment of dollies, golf carts, ramps, and elbow grease. There’s a really neat crane shot that I can’t quite grasp the logistics of where it moves along the ground and then rises up over a baseball field. I watched the film without knowing of the failed SkyCam, and the depictions of flight that made the final cut worked for me. Also consider all of the scripted moments that required performance from animals; trainer Gary Gero worked with “eighty canaries, pigeons, a tropical hornbill, a cat, eighteen dogs and a seagull—all of which had their moments on screen.”

I would be remiss not to mention the contributions of Peter Gabriel. It was his music, in fact, that initially put Birdy on my radar (I went through a Gabriel phase in college). After leaving Genesis, he had explored all sorts of musical styles—drum machines, African rhythms, reverb, sampling, synths, etc. Parker had cut half the film and overlaid some scenes with snippets from Gabriel’s four self-titled albums before it was presented to the experimental pop star. Gabriel was already late in delivering his next solo album (1986’s megahit So), so instead of coming up with a completely unique soundtrack, Gabriel and Daniel Lanois remixed instrumental tracks from his older material. And it works so well that it’s hard to imagine the film without it. It moves from ethereal to arresting, whatever the material calls for. Particularly compelling is a contemplative scene narrated by Modine set to “Quiet and Alone” that transitions into a dream flight accompanied by “Birdy’s Flight”. I’d almost go so far as to say that the music is as integral to the tone and emotional resonance of Birdy as the two central performances. (There’s also the recurrent use of “La Bamba” which feels weird but whatever.)

Birdy is a wonderful, overlooked gem of the 1980s. I’m a little bit conflicted on the uplifting ending—it just felt like the buildup deserved a super bleak conclusion—but everything else is inspired. Direction, performances, editing, music. Good stuff.

1. Though I don’t want to dwell on it, I’ll mention in passing that, although many have tried to make Birdy into some subliminal homoerotic fantasy, it is definitely not. In fact, it explicitly states several times in the film that it is not. In response to a probing question from the military doctor, Al states outright, “we weren’t queer for each other or anything like that.” Al is also shown repeatedly making advances at women. There’s an amusing moment when the pair are walking on the beach discussing Birdy’s lack of game and Al is speaking of the female breast with awe. “We’re talkin’ tits here,” he says. But Birdy’s seen those in National Geographic. They’re just like cow’s udders except in a weird place. Anyway, it is a sign of the times that people feel the need to twist depictions of genuine friendship to fit a depraved worldview. If you can’t fathom a loving relationship between two men being nonsexual in nature then you are an unfortunate victim of the zeitgeist. Plus, if we want to push on the suggestions offered in the film, Birdy seems much more interested in making love to his canary than to any human—man or woman.

Sources:

Parker, Alan. “Birdy—The Making of the Film, Egg by Egg”. AlanParker.com.