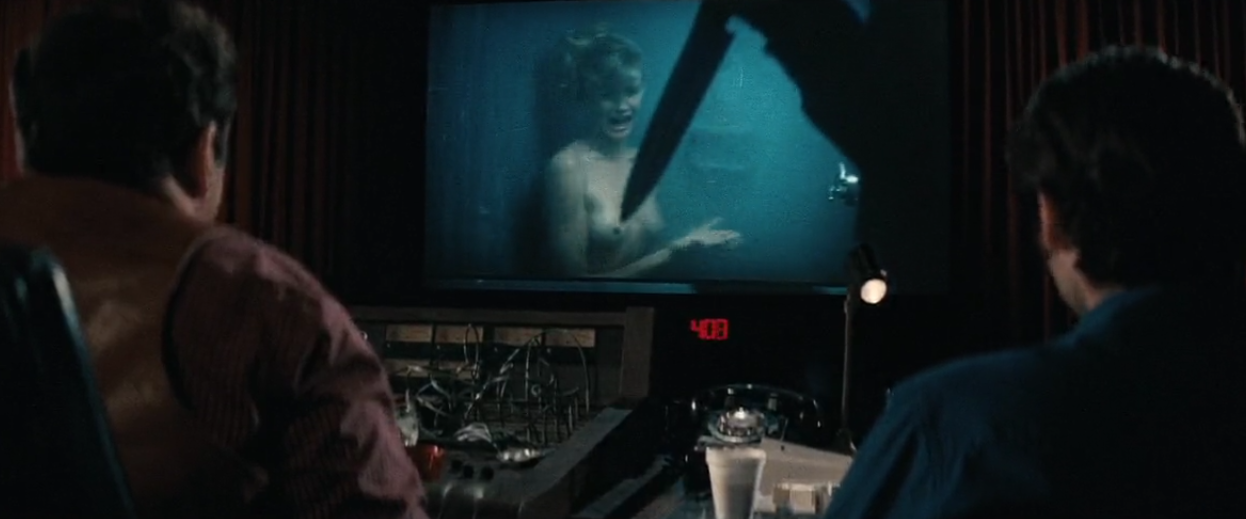

“I didn’t hire her for her scream, Jack, I hired her for her tits!”

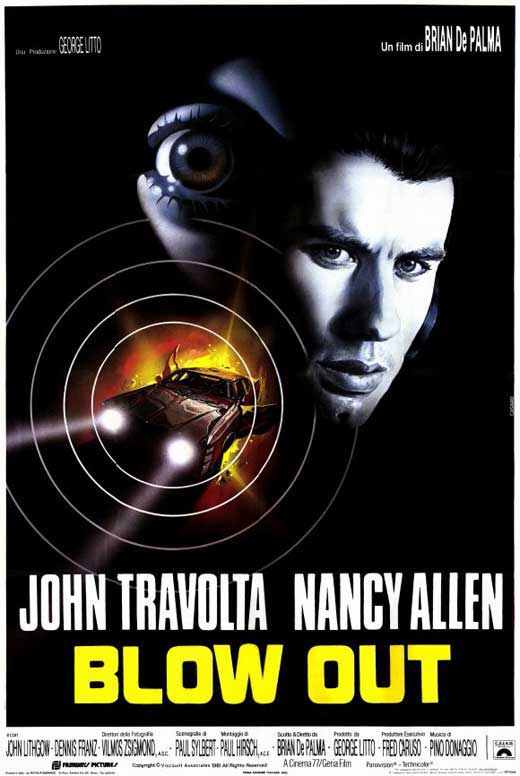

De Palma had been on an upward trend for a decade when he made Blow Out. Crafting a paranoid thriller overflowing with effortless style, the director was clearly in some kind of artistic sweet spot when he made what many view as his career pinnacle (even though it flopped upon release). Placing a bold emphasis on the realm of sound and the tactile elements of film construction, the giallo-tinged pulse raiser plunges the viewer into a political conspiracy when a man unwittingly records the murder of a popular presidential candidate. Cleverly mixing the hooks from Coppola’s sound-driven The Conversation1 and Antonioni’s photographical Blow-Up, and maybe a hint of Powell’s Peeping Tom, De Palma’s stylish film opens masterfully and builds great momentum until shakily landing a trick climax in its final moments.

It is not difficult—and many others have already done this—to see Blow Out as a meta film that showcases the filmmaking process. Jack Terry (John Travolta) is a sound effects specialist for a small studio that pumps out sleazy slasher flicks, and as such he’s well acquainted with the ins and outs of film production. When fate dictates that he record the sound of a murder, he spends the next several days in a frenzy recreating the scene by syncing amateur-shot film frames from a magazine with his audio recording, marking up film rolls, rewinding and replaying, copying, etc. As he diligently examines his recording and the peripheral evidence, and discusses the event with Sally (Nancy Allen), he pieces together a coherent narrative in the same way a director or writer does when pulling together the various threads and ideas that belong in the film. It feels a little bit meta, but it should be stressed that not a single ounce of entertainment value is sacrificed on the altar of arthouse. This is a rare treat, where a filmmaker at the top of his game channels his flamboyant tendencies into a coherent, sublime thrill ride.

Jack’s been sent by his producer to collect various rustling sounds and a better scream for their schlocky slasher film Co-ed Frenzy—briefly shown in a satirical POV opening scene that echoes the opener from Halloween. This intentionally shoddy snippet lacks power because all of the characters shown in the (tactically brilliant) long take are anonymous; we don’t really care that a stalker knifes a woman in the shower because the woman is unknown to us. When she screams, De Palma cuts for the first time to Jack and Sam (Peter Boyden) sitting in the studio, arguing over the quality of the bimbo’s weak caterwaul. Sneakily—because even though a few interludes remind us that Jack is supposed to be making a movie, it’s easy to forget his actual occupation amidst his amateur detective work—De Palma then makes an entire movie to show us that it takes more than just a sneaking predator and a screeching wail to shock an audience; it also requires empathy for the victim, a crucial element that is often lacking in weaker films. The genius shock twist that ends Blow Out is the kind that makes you almost question your affinity for the film as a whole and may require some mental processing to come to terms with.

From a river bridge outside of the city, Jack records the soft murmuring of a pair of lovebirds, the croaking of a frog, and the hooting of an owl. All of these are presented using slick split diopter shots allowing for the creative use of pseudo deep focus. The silence is interrupted by the sound of screeching tires, a gunshot, a tire blow out, and a crash into the water. Jack immediately springs into action and dives into the water, and although the presidential candidate remains in the depths, he’s able to rescue Sally (Nancy Allen), a call girl who was with the politician. Jack and Sally are, for all intents and purposes, merely two loose ends on a perfect crime. A fixer named Burke (John Lithgow) is a half-step behind them for much of the film, blocking phone lines, swapping out the bullet-ridden tire, posing as a newspaper reporter, and strangling prostitutes at random.

A large chunk of the film consists of Jack working assiduously in a constant state of anxiety and mistrust. He’s approached by several journalists, badgered by his boss, and on uncertain terms with Sally. De Palma and his leading man manage to make the dirty work of evidence processing engrossing, engaging us both visually and aurally. As his obsession with creating a coherent patchwork of evidence mounts, our investment in his story grows with it. Travolta is great here—his hands look like they know their way around the equipment, and he’s given opportunities for emotional depth. There’s a flashback scene of a wiretap mission gone bad that brings out the best in him. Playing off of Travolta is Nancy Allen (married to De Palma at the time), who excellently portrays a smart and cunning woman acting like a caricatured gum-chomping airhead. Having saved the life of the make-up artist/lady of the evening, Jack pokes a hole through her facade and realizes that he is drawn to her wobbly charm. She’s variably vulnerable and closed off, shallow and sophisticated, naive and shrewd.

De Palma gradually steers us toward a bitterly ironic gut punch of an ending. The inhuman Burke, driven by an insatiable bloodlust, tracks down Sally and tricks her into meeting with him privately. Although wiretapped by Jack to avoid any trouble, she is outwitted by Burke and boards a train with him. In the bustle of a citywide parade, Jack fails to come to Sally’s rescue and must watch in horror from afar as she is strangled to death by Burke. Arriving too late, he stabs Burke to death. Ironically, tragically, he’s left with a recording of Sally’s scream—a genuine wail of terror that Jack and Sam both agree is perfect for their low budget horror film. De Palma had done longform humor before, but never quite this sick.

Unlike some of the films that inspired it, Blow Out does not get too abstract or puzzling. It never wavers in its commitment to entertain. One could watch it straight through as a pure cinematic thrill ride without a hitch. But De Palma also has much more to say here regarding the technical manipulation of the completed film and the differences between reality and “the narrative.” An all-around magnificent piece of filmmaking that only a few auteur directors working today would be given the freedom to make.

1. There’s an interview from Filmmaker’s Newsletter from May 1974 in which De Palma interviews Coppola about The Conversation and it’s almost as if you can see the concept of Blow Out forming in his mind in real time. It’s available in its entirety at the Cinephilia & Beyond link below.

Sources:

Mikulec, Sven. “Brian De Palma’s ‘Blow Out’ is one of the finest films about the process of filmmaking”. Cinephilia & Beyond.