“What’s your predilection, mister? You look like you could use something potent. Or omnipotent.”

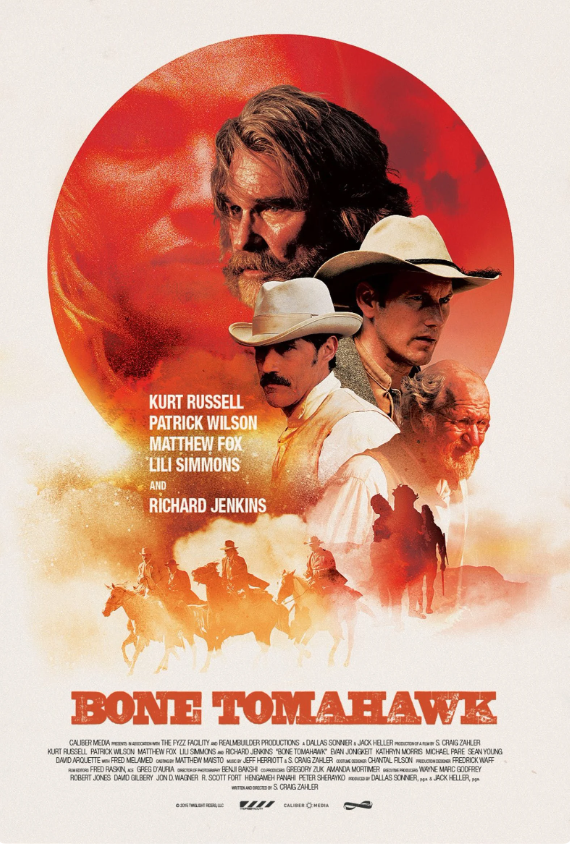

When two cutthroats (David Arquette, Sid Haig) disturb the burial site of an inbred cannibalistic Indian tribe, they unwittingly bring the wrath of the ruthless troglodytes down upon the nearby frontier town of Bright Hope—a small community sparsely populated with colorful personalities, four of whom embark on a doomed journey to rescue the abducted Samantha O’Dwyer (Lili Simmons). Among them are Arthur O’Dwyer (Patrick Wilson), the lady’s husband who’s laid up with a broken leg; Sheriff Hunt (Kurt Russell), a hair-trigger lawman with a penchant for maiming strangers with his revolver; John Brooder (Matthew Fox), a debonair gunslinger; and Chicory (Richard Jenkins), a loquacious old-timer serving as backup deputy.

“If Tarantino made a Western-horror hybrid” is perhaps too reductive a description of Bone Tomahawk, the glorious debut from writer-director-composer S. Craig Zahler, but it puts us in the right ballpark. Certainly one need not stretch the imagination too far to envision the genre virtuoso himself conceiving the richly drawn residents of Bright Hope and filling their mouths with dialogue as quotidian as it is intriguing. Consider Chicory, the most obviously Tarantino-esque character (though he also echoes Walter Brennan’s Stumpy from Hawks’ Rio Bravo). He’s introduced to us when he remarks that Sheriff Hunt’s tea smells “gruesome,” only to request a cup of it when he is informed it is actually corn chowder. He repeatedly refers to himself in the third person when he offers “the official opinion of the backup deputy.” For instance, during his evening promenade he spies Purvis (Arquette) acting in a suspicious manner and reports his official opinion to Hunt, who promptly acquaints himself with the outlaw drifter in the nearby saloon and then shoots him in the leg. When Brooder produces a flashy spyglass he calls “the German,” Chicory develops a minor obsession with it. Most delightfully, Chicory offers regular, extended asides that provide macabre humor and serve as cinematic trail markers—about the futility of trying to keep a book dry when reading in the bathtub, about the authenticity of flea circuses. And that’s to say nothing of the charming tics that define the others and their conversational interplay.

One area where the two directors clearly differ, however, is in their depiction of violence. Tarantino certainly knows how to use shock value and gore—the severed ear in Reservoir Dogs, Marvin’s untimely end in Pulp Fiction, decapitations and geysers of blood in Kill Bill Vol. 1—but it’s usually stylized and triumphant and never comes at the expense of entertainment. He can get a little bit nasty, too, such as the mandingo fight in Django Unchained or the gunpoint rape in The Hateful Eight (a deliberately-paced, violent Western that came out a few months after Bone Tomahawk and also stars Kurt Russell, and is thus an interesting companion piece). But Zahler, hoo boy. Zahler stages his violence in a manner that is at once both nonchalant and visceral. The film opens with Purvis sawing through the neck of an unfortunate traveler, and features in its climax one of the most heinous cinematic deaths I’ve ever seen.

Speaking of that extremely graphic inverted evisceration, I find it quite laudable that Zahler manages to thread the needle and offer a film that is neither a Western with flashes of horror nor a horror flick with Western trappings, but a genuine hybrid of cowboys-and-whiskey Americana and blood-and-guts schlock that can fully satisfy both camps (but is of particular delight to fans of both). It takes the familiar narrative shape of a Western—the most commonly cited touchstone is John Ford’s The Searchers—but is set in an American West that is stripped of its mythical qualities, a place where broken bones lead to gangrene and exhausted horses collapse beneath their riders. In place of that shopworn folkloric texture is a compelling mixture of gritty realism and wanton brutality.

The horror sneaks up on the story slantwise, making slight inroads amidst the meandering conversations before completely taking over in the finale. If at first it recalls the Classical Hollywood Westerns, or even revisionist pictures like Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch or Eastwood’s Unforgiven, as it steadily winds its way through the desert toward the tribe’s foreboding mountainside cave it increasingly evokes gorefests from Italian directors like Umberto Lenzi (Cannibal Ferox, Eaten Alive!), Sergio Martino (The Mountain of the Cannibal God), Joe D’Amato (Absurd), and Ruggero Deodato (Cannibal Holocaust). It never shifts its emphasis entirely to splatter and viscera, and, relative to those “video nasties,” has spent considerable effort building up its characters so that we’re as invested in their little personal dramas as we are their mission, but when it swings its few wicked haymakers it lands them.

A literate, borderline-parodic Western shot through with Italian schlock horror is necessarily looking for a niche market, hence why Bone Tomahawk received only a cursory theatrical release. But in his debut, in addition to his strong work as a screenwriter, Zahler proves a capable director in his control of tone, pacing, and performance, producing a subtly ambitious triumph of genre blending for a paltry sum.