“I don’t know about any of it, nobody does. Except the Almighty, and He seems to be on sabbatical.”

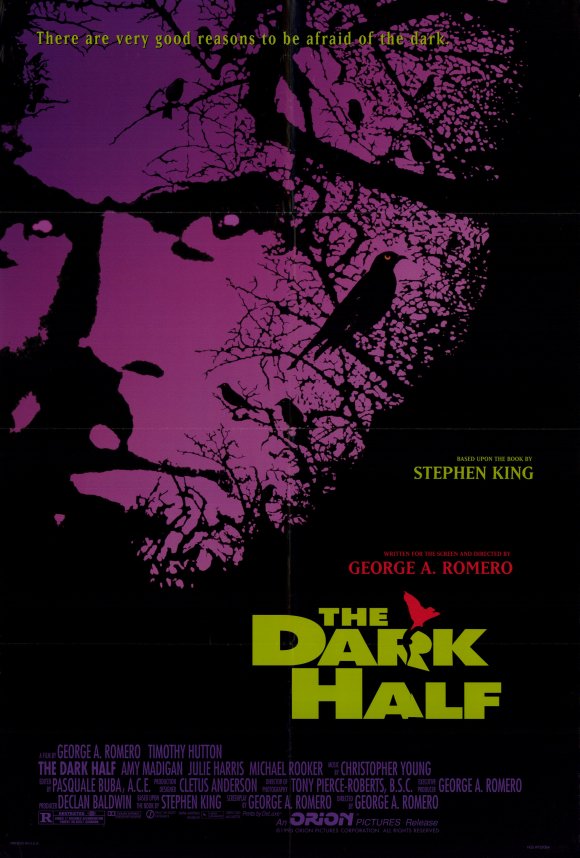

In the 1970s, Stephen King began writing under a pseudonym to get around his publisher’s limit of one book release per year. This allowed him the chance to prove to himself that his talent, and not just luck, was responsible for his massive popularity. His King books were key in developing a popular taste for the macabre, but his works published under the name of Richard Bachman were heavier—more visceral and cynical than the “Big Mac and fries” to which he famously likened his regular fare. The Bachman books sold decently well, but not like the King books. And when his alter ego became public knowledge, sales shot up drastically, leaving his talent/luck question without a satisfactory answer. Responding to the outing in the most stereotypically Stephen King way possible, he wrote The Dark Half, a novel in which a writer’s pseudonymous doppelgänger supernaturally manifests itself and fights for its own “life.” George Romero, another godfather of the macabre, directed the film adaptation—his second King collaboration (the first being Creepshow).

Timothy Hutton stars as both the author and his evil twin, sinking his teeth into the delicious pulp of King’s autobiographically-tinged slasher story. Thad Beaumont is a university lecturer who writes highbrow literature that nobody reads. It’s sophisticated, artful, and too abstract for the popular palate. George Stark, on the other hand, writes best-sellers starring a rough-and-tumble anti-hero named Alexis Machine. Thad channels his Mr. Stark personality when he wants to indulge in vice and sadism—drinking, smoking, and writing pulp only when he’s assumed his alter ego. But a sleazy opportunist has seen past the façade and confronts Thad about it, attempting to blackmail him out of a portion of his modest fortune. Rather than cower in fear and pay up, Thad and his wife Liz (Amy Madigan) decide that Thad will go public and own up to the name of George Stark. And thus begins an atmospheric slasher flick.

Sensing his imminent demise, George somehow generates a physical form and begins terrorizing people in Thad’s life. For a brief period, we suspect that Thad may be committing the crimes while in some kind of fugue state—his fingerprints are found in a murdered man’s blood, a grave is dug up at his family’s plot, and Thad’s blackmailer is found with his own detached manhood shoved down his throat. But when we finally meet George Stark face-to-face, it’s clear that they are physically distinct characters. Both the makeup team and Hutton deserve a lot of credit for making George Stark such a convincing character distinguishable from Thad Beaumont. There are clear yet subtle alterations to Hutton’s facial structure and skin, and he walks with a swagger and talks with a drawl when portraying the fiend. He portrays Thad as clumsy and excitable, George as methodical and imperturbable. Their distinction is made more apparent as Stark begins succumbing to an unknown disease, actualizing his symbolic death as a result of Thad going public with his pseudonym.

The origins of George Stark are a little bit flimsy but full of juicy imagery and thematic significance. Early in the film, when Thad is still very young, he begins experiencing blackouts, headaches, seizures, and phantom birdsong. The doctors slice him open, planning to remove a brain tumor that they believe is the culprit. But upon commencing the probing, they discover the remnants of a mostly absorbed parasitic twin—teeth, hair, and a fully developed eye that peers back at the surgeons. A massive flock of sparrows converges on the hospital as the tumor is removed. This horrific little scene gives the film a macabre tonal quality similar to that of De Palma’s Sisters. It is never made clear what link exists between the excised twin and George Stark, but it doesn’t really seem to matter. The only thing we know for certain is that when Thad publicly owns the name of George Stark, goes through the magazine interview, mock funeral, and photo shoots, George doesn’t go down without a fight.

The Dark Half exceeds its modest ambitions on several fronts. One of the traits I admire in Stephen King’s writing is how he effectively cobbles together characters around little tics. For instance, you’ll remember photographer Homer Gamache (Glenn Colerider) because of his repeated use of the word “folderol” and his optimistic demeanor. Gamache is only on screen for a short amount of time before George Stark, posing as a hitchhiker, lures the old man to a stop, rips him from his truck, and beats him to death with his own prosthetic leg. The cop who discovers the gore-filled abandoned truck repeatedly speaks out loud to his mother to quell his fear. These are throwaway characters made memorable by idiosyncrasies. But Romero deserves a lot of credit for his restrained direction. The director’s most popular films are his zombie movies, which are more or less clear about what is happening in the story. But in The Dark Half, the lines between the inner and outer world blur, time is diluted, and two persons emanating from the same mind clash together in a battle of wills. There are moments of trashy fun throughout the film (“What’s going on?” “Murder… ya want some?”) but Romero elegantly manages to keep the pulpy shenanigans from detracting from the dramatic arc.

Before all the hooey starts to hit the fan, while Thad’s still teaching classes, he delivers a lecture on the duality of man—the battle between our inner and outer selves. It’s barely explored, but points to the idea that man is a multifaceted being, that moods can take us and pervert our behavior, that our temperament and personality are not static things. George Stark is a severe example of that idea escalated into absurdity as he cleans house with a straight razor. But the inspiration for the story—King’s struggle to sacrifice Richard Bachman—comes through very clearly in Thad’s reluctance to permanently seal Stark’s fate.

Though Romero preferred to work on the fringes of the industry with low budgets, he shacked up with a studio for The Dark Half. Said studio granted him a significant budget and a talented leading man, but also the oversight that he disliked so much. There were some issues during the shoot as well as an unfortunate delay in filming when Orion ran into financial troubles. But the completed picture bears only a few marks of the behind-the-scenes issues. In any case, whether due to the ambiguous origins of the villain, an oversaturation of Stephen King in 1980s and ’90s cinema, or the nearly two year gap between wrapping the shoot and the finished version hitting theaters—The Dark Half was a box office bomb. Criticism largely focused on the loose nature of George Stark’s character. Even in the story, Sheriff Alan Pangborn (Michael Rooker) pleads with Thad that he cannot fathom what he is up against. Thad, too, is at a loss, and only a vague suggestion from his academic colleague that it’s “an entity created by the force of your will” does anything to elucidate the subject. Some further pondering could have served here, as the mystical concept of a tulpa is one that has been talked about enough (and utilized for maximum surrealism in Twin Peaks: The Return). With this vagueness in mind, the mano a mano finale can’t really have a concrete meaning. It doesn’t answer any of our lingering questions, maybe even leads to some more, but it at least gets rid of George Stark once and for all.

I think the ambiguity bothers me less than the average viewer, so I liked The Dark Half quite a bit. Romero skillfully hides the rough edges beneath the stylistic gore that Stark whips up, and shows off his more abstract side by delving into Thad’s inner life. Hutton commits fully to both roles, clearly enjoying his against type portrayal as the hokey Elvis man ripping at throats. It probably could have done with a more eager editor to trim things another fifteen minutes or so, but that should not deter anyone. Though it’s obscured by the popular work from Stephen King and George Romero, The Dark Half is a film ripe for rediscovery that is only a tier below their best.