“We don’t want other worlds. We want mirrors.”

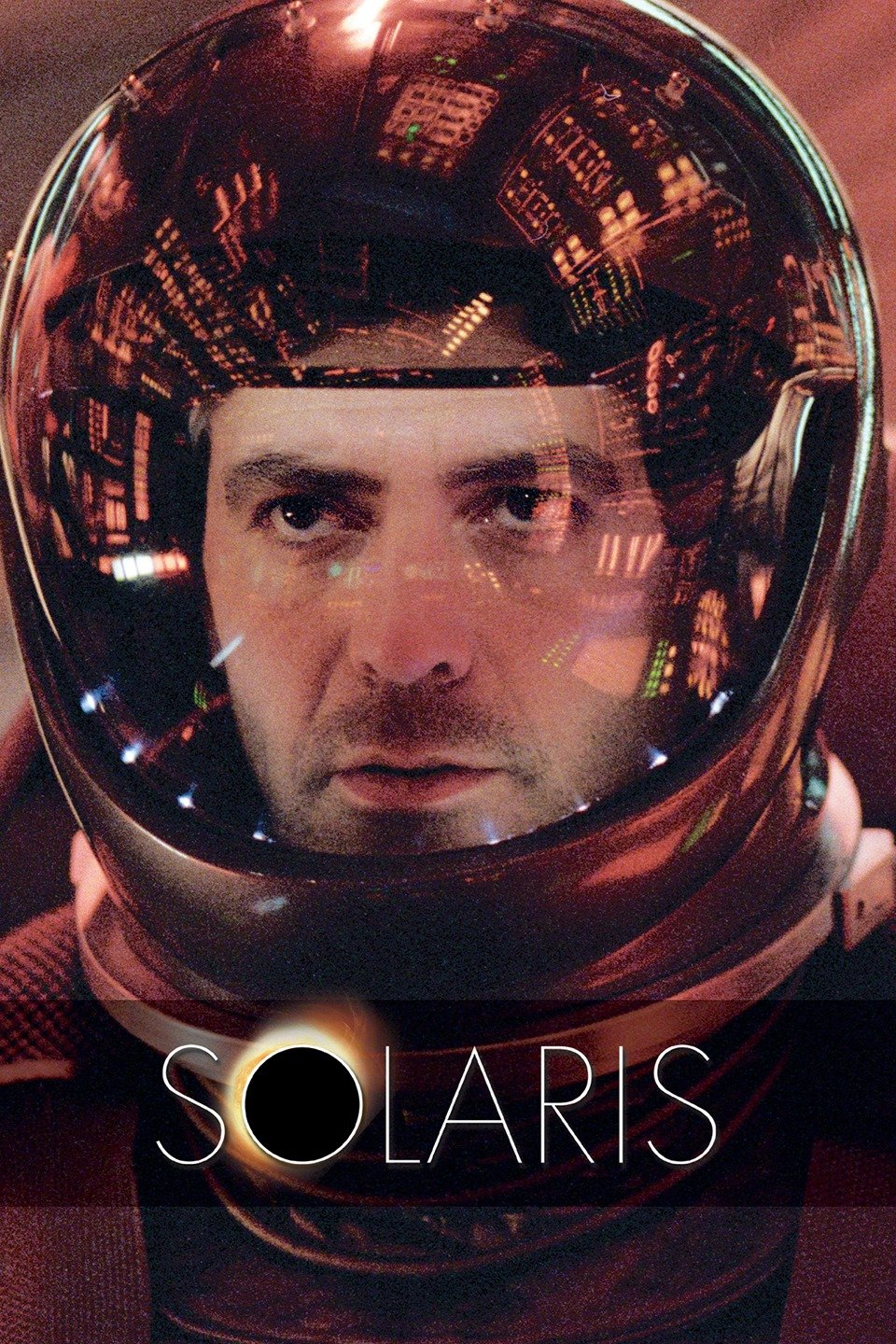

You have to admire Steven Soderbergh’s chutzpah, and many of his other qualities besides. Unpigeonhole-able, the maverick filmmaker’s career has been marked by extreme productivity, a charming DIY attitude (he’s often director, screenwriter, cinematographer, and editor of his films), and a chameleonic ability to jump between genres and markets. Indeed, he seems to be quite fond of building up street cred with prestige pictures and popcorn munchers and then trading it all in on curveball projects. Case in point is his 2002 remake of Andrei Tarkovsky’s meditative arthouse masterpiece, Solaris.

Clocking in at an hour and change slimmer than the earlier film, which is as somnambulant as it is enthralling, Soderbergh’s version is more economically arranged but no less ruminative. Quickly establishing an uncanny sense of disorientation in which past and present coincide, dreaming and waking states blur together, and earth and outer space overlap, the mysterious events of Solaris unfold in an unhurried fashion that never languishes nor loses its steady grip on the audience’s emotions.

For better or worse, Solaris is an arthouse film through and through. It is likely that mainstream audiences unfamiliar with Tarkovsky’s slow-burning classic were expecting something a bit less abstract. A sci-fi adventure complete with bug-eyed aliens, futuristic tech, and lightspeed travel, perhaps. Instead they received a sci-fi film in name only. Set against a backdrop of space exploration and the discovery of a distant planet that shows signs of sentience, the film nevertheless neglects to deliver the kind of rollicking entertainment generally associated with the popular works in its genre. In lieu of such provisions, Soderbergh uses his unique source material to cover similar themes as the original—loss, remorse, yearning, loneliness, fate—but in a less cerebral, more narrative-driven fashion.

The film stars George Clooney as Dr. Chris Kelvin, a clinical psychologist whose presence is covertly requested by the Solaris research team. The small group of scientists who have been living in orbit around the faraway planet find themselves confronted with a phenomenon so mysterious in nature that Kelvin’s friend and colleague Dr. Gibarian (Ulrich Tukur) dares not try to verbalize it in his video message. Arriving on the station full of apprehension, Kelvin finds Gibarian zipped up in the morgue. Another team member has apparently disappeared. The only two surviving crew are the shifty Dr. Snow (Jeremy Davies) and the paranoid Dr. Gordon (Viola Davis). Neither are willing to enlighten Kelvin to the strange happenings aboard the station, but he finds out soon enough when he awakens from his first night in his new lodgings to find Rheya (Natascha McElhone) in his room—Rheya, his dead wife.

There’s little doubt that it is the planet itself, Solaris, that is manifesting these tulpas by drawing on the memories of the station’s crew. But there is less certainty about how to deal with these beings. Abandon them and return to Earth? Destroy them? Treat them as human? It’s clear that they’re not hallucinations, they’re not ghosts. But what are they?

Kelvin: Who is it? What is it? Does it feel? Can it touch? Does it speak?

Gordon: We are in a situation that is beyond morality.

What follows is an exquisite examination of love and death and memory. Soderbergh’s brilliant stroke here is in how gradually he allows the pieces to fall into place, how he allows Kelvin to exhibit shock and disgust upon seeing his dead wife resurrected, only to slowly come around to the idea that fate or the God he doesn’t believe in might have offered him a peculiar second chance. In bits and pieces, we glimpse Chris and Rheya’s romance and the tragic ending of Rheya’s life, including the psychologist’s unfortunate hand in it. But even as Kelvin begins to warm to the idea of living out his days on the station in order to spend them with the reborn Rheya, interpreting her presence as a blessing from Solaris, the levelheaded Gordon believes that the planet is a malevolent force attempting to drive the crew insane.

The performances are mostly good—particularly the supporting actors. Davies’ evasive speech patterns and eccentric mannerisms provide some oddball humor while Davis’ paranoiac scientist acts as a minor antagonist in Kelvin’s weird arc. These roles both work well because, as Gordon notes, there’s not an ingrained human response to this predicament. We don’t know who is in the right and so there’s constant tension. In any case, the true standout here is McElhorne as Rheya, who imbues her two iterations of the character with enough subtle differences that her detached and uncertain “alien” version is legitimately creepy. If there’s a flaw in the casting of Clooney, it’s simply that he’s too much of a prototypical charming lead to ever disappear entirely into the somber role of Kelvin.

Where Soderbergh’s streamlined narrative structure and pointed themes might lack the lyricism and profundity of Tarkovsky’s brooding treatise, they certainly deliver an emotive drama. Supported by Cliff Martinez’ tender score, Solaris provides an affecting story in which the past and the present plot lines converge at the same time in a poignant crescendo. Soderbergh is dialed in with his use of flashback, taking us through the phases of Chris and Rheya’s lives, jumping between them or keeping one foot in each reality as he sees fit. There are a few instances in the script where the concise nature of the storytelling leads to some heavy-handed lines, but on net Soderbergh’s work as a quadruple threat is commendable.

Remakes are a dime a dozen in modern Hollywood, the kind of films that are often preemptively dismissed, and justifiably so. Most remakes and/or reboots are just nostalgia-based cash grabs. Not Soderbergh’s Solaris—which, it must be noted, is less of a remake than a fresh adaptation of Stanisław Lem’s novel (Lem disliked both adaptations, for what it’s worth). Unfortunately, Soderbergh’s film suffered for defying genre conventions. It’s a shame, because it’s everything emotional science fiction should be—disturbing, beautiful, heartbreaking.