“I guess if you’ve got some cold bologna, mayonnaise and bread I’ll hang around for a while.”

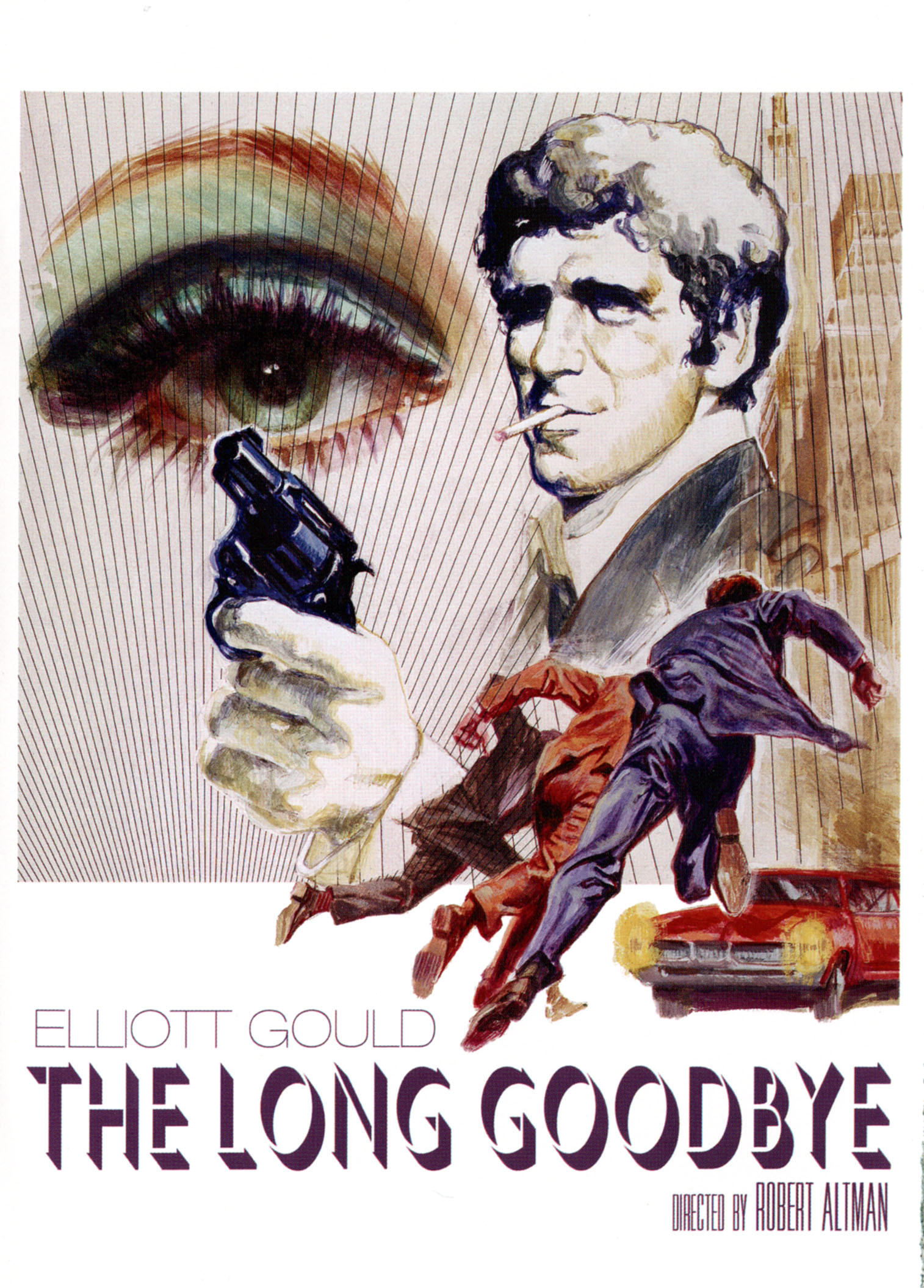

Raymond Chandler’s wisecracking private detective Philip Marlowe has been portrayed by numerous actors over the years, most famously by Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep. That novel and Howard Hawks’ film adaptation are considered pinnacles of the hardboiled crime fiction genre, while Chandler’s more personal, experimental The Long Goodbye proved more divisive. In Robert Altman’s adaptation Elliott Gould portrays the gumshoe, who finds himself caught in a hazy web of deception as he tries to absolve his friend of a murder accusation. Ambiguous threads, partial resolutions, and red herrings render the plot murky to the point of impenetrability as Marlowe half-heartedly tries to track down a suitcase of stolen money and prove his friend’s innocence. But The Long Goodbye does not rely on an airtight story, or even a faithful depiction of its main character; rather, Altman’s subversive style—which encourages loose, overlapping dialogue, scenery chewing, and improvised acting and lensing—coalesces into a moody, supple take on film noir that undercuts the genre’s fundamentals with wry humor and cheerful admiration.

I’m not very familiar with Chandler’s work, but I’ve seen several adaptations of his Marlowe novels, all but one of which have received movie treatments (and some of them more than one). This one isn’t like the others. Early depictions of Marlowe are laconic, guarded, and principled; he’s an amalgam of 1950s coolness—he drinks, he smokes, he entices women, he carries a gun that he seldom uses, and his moral compass and detective instincts are impeccable. He’s a lone wolf living by a righteous code. But The Long Goodbye, at least Altman’s version, is not set in the 1950s but in the 1970s. Our classic private detective is in unfamiliar territory here, transported from a straight-laced era to one where his neighbors are a handful of hippie chicks who do yoga in the nude and eat magic brownies. He still wears his nice suits, chain smokes, cracks wise, and lives by a code, but this Marlowe is decidedly a novel creation.

This fish-out-of-water element pairs well with the change in narrative voice. Earlier renditions of Marlowe, and the books themselves, have a certain precision, whereas Gould’s Marlowe prefers to navigate his life with the continuous buzz of bemused self-commentary, delivered in a dryly humorous mumble. The whimsical tone is set brilliantly as Marlowe awakens in the middle of the night to his cat’s persistent meowing. The cat is hungry, but will only eat a specific brand of wet cat food. Marlowe’s fresh out, and his tricky concoction of leftovers doesn’t fool the feline, so he takes a walk to the corner store in search of the stuff. He waggishly commentates his trip and has brief exchanges with the yoga girls, the celebrity-impersonating security guard, and a store clerk. The scene has very little narrative significance but it is a delightful bit of characterization and mood-setting.

And mood is really what makes The Long Goodbye so much fun. I’ll sketch out what I understood of the plot, but I wouldn’t recommend you come at it expecting much satisfaction from it in terms of a polished, cohesive story; in fact, the same ambiguities that detract from its narrative thrust help to bolster the lackadaisical atmosphere that makes it feel so distinct. After his trip to the corner store, Marlowe receives a surprise visit from his friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton1) who requests Marlowe drive him from L.A. to Tijuana where he will cross the Mexican border. Like a good friend, Marlowe obliges without question. When he arrives back in L.A. he is arrested for aiding in Lennox’s escape—it turns out his friend has beaten his wife Sylvia to death. Marlowe is held for three days, then released when news of Lennox’s suicide surfaces. It’s an easy case for law enforcement, but Marlowe doesn’t buy it.

In a seemingly unconnected case, he’s hired by the alluring Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt) to track down her missing husband Roger (Sterling Hayden), a once-popular author whose writer’s block has cause him to abuse both alcohol and spouse. While fetching Wade from a high-end detox clinic run by the manipulative Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson), he learns that the Lennox and Wade families were familiar with one another. He becomes somewhat involved in the Wades’ affairs, travels to Mexico twice, witnesses a suicide, and watches with horror as gangster Marty Augstine (Mark Rydell) tries to intimidate him by raking a broken Coke bottle over his own girlfriend’s face. As he stumbles his way through his informal investigation in and around the ritzy beachside community called Malibu Colony, his case is built on intuition informed by misdirection. Was Roger sleeping with Sylvia? Does Eileen want to seduce Marlowe or divert his attention? Is she driving her husband toward self-destruction or trying to help him? Who owes money to who? It takes a long time until it becomes possible to make sense of the links between Marlowe and Eileen, the Wades and Lennox and Augustine, and everyone and the suitcase full of money. And even when Marlowe confronts his disloyal friend at his hideout in a Mexican villa most of the loose ends remain so. For the bulk of the duration, our languorous protagonist is just stumbling from one incongruous clue to the next.

It may not sound very exciting on paper, but that’s what makes the auteur’s work so much fun to dig into. Lay this out in sketch form, it looks okay; tell me it’s Altman and it immediately piques my interest. His best films have a sparky spontaneity and hint of randomness that buoy his meandering narratives. Watching The Long Goodbye almost fifty years after its release, I’m struck once again by how much leeway the New Hollywood directors were given to craft their idiosyncratic visions, and just how tame and polished (and so often boring and stale) mainstream movies are today. Having Marlowe mumble to himself, miss crucial bits of dialogue, strike his strike-anywhere matches literally anywhere, complain that brownies hurt his teeth and apricots give him diarrhea—these things could be thrown away, but they add so much character that they become indispensable for conveying the mood. Other odd inclusions that serve a similar function are Ken Sansom as a security guard who impersonates celebrities, including Barbara Stanwick, Jimmy Stewart, Walter Brennan; a man in a full body cast who gives Marlowe a tiny harmonica, which he plays for himself after dealing with Terry in the climax; Roger Wade refusing to call Marlowe anything but “Marlboro”; and of course, the uncredited Arnold Schwarzenegger (in his second film appearance) stripping down to his underpants.

Streamlining the central mystery of Chandler’s novel, Altman clears the stage for his team to shine, and they all step to the plate. Elliott Gould’s mumbling, free-associative take on Marlowe is terrific, characterized by ignored one-liners and a detached stoicism. Likewise, the commanding, scenery-chewing performance by Sterling Hayden is fun and memorable and would not have been possible without Altman’s encouragement of his actors to improvise on set. And Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography expertly captures the beaches, landscapes, and architecture of L.A. and the characters that inhabit them, even allowing for Altman’s freewheeling direction. The Long Goodbye is a wayward, vaguely melancholy film that really struck a chord with me.

1. Bouton was a New York Yankees pitcher, World Series champion, best-selling author of a baseball memoir, and co-creator of Big League Chew. I’m not sure how he ended up getting a small part in an Altman film.