“I’m not just talking about one person, I’m talking about everybody. I’m talking about form, I’m talking about content, I’m talking about interrelationships. I’m talking about God, the Devil, Hell, Heaven. Do you understand… finally?”

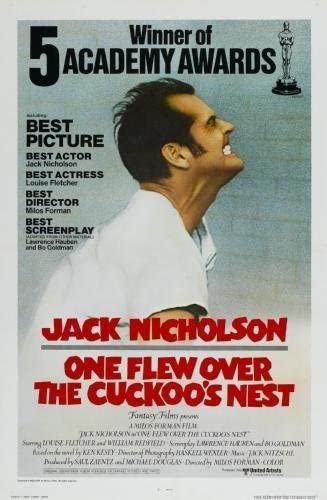

One of three films1 to sweep the “Big Five” at the Academy Awards—Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Director, Best Picture, and Best Screenplay—director Miloš Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a powerful film deserving of its accolades. Based on Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel of the same name, the film takes place in a psychiatric hospital with a narrative that illuminates the institutional practices of such a facility, the intricacies of the human mind, in addition to critiquing behavioristic psychology and commending the individualist mentality.

Jack Nicholson stars as Randle Patrick “R.P.” McMurphy, a questionably sane convict who is sent to the institution as punishment for troublemaking and laziness. He is charismatic and talkative, and the ward’s drugged and lethargic patients soon come to view him as their leader. The ward is overseen by the stern and orderly Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), who leads the men through group therapy sessions and regularly doses them with tranquilizers.

McMurphy’s extroversion and livewire antics do not allow him to sit still, and he soon enlists his wardmates in a game of intentional defiance of Nurse Ratched. In some of the film’s most touching scenes, McMurphy’s little game turns into spontaneous and innocent episodes of joy for the patients—McMurphy teaches the vertically gifted but dumb and mute Chief (Will Sampson) to play basketball with them against the orderlies, and adlibs color commentary for the World Series game that they are not allowed to watch.

Too late, McMurphy realizes that he cannot leave the institution without the consent of Nurse Ratched and the Dr. Spivey (Dean R. Brooks), and that his defined prison sentence has now become an open-ended stay at the ward pending his psychiatric assessment—an assessment he had been all too willingly flunking. Angered, he leads a revolt, breaking out of the ward and commandeering a boat and taking the other patients on a fishing trip; oh, and he also takes his girlfriend/hooker Candy (Marya Small) along as well.

After being administered electroshock therapy, things continue to go poorly for McMurphy. He and Chief (who, as it turns out, can hear and talk) plan to escape, and McMurphy buys off Turkle (Scatman Crothers), the night orderly, so that he can have a going away party. Things go awry—the party becomes an all night boozed up orgy—and the men awaken hungover in the morning.

Nurse Ratched tries to publicly humiliate Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif), who is found in bed with Candy. Though the stuttering youngster—who is in the ward voluntarily—bravely stands up to her, when she threatens to tell his mother what he has done, he loses control of himself, and commits suicide. Enraged, McMurphy tries to strangle Nurse Ratched. To follow up that sad note, the film ends with McMurphy returning to the ward after some time separated from his ward mates; Chief goes check on him, and finds him unresponsive and limp, with lobotomy scars on his forehead.

There are several different ways to read the film,2 including viewing the psych ward as the state, or emphasizing the patients’ voluntary subjugation to arbitrary sets of rules. But I think its clearest message is the value of friendship. McMurphy is adamant about obtaining freedom—always pushing the limits, testing his boundaries, making plans to flee to Canada—but given ample opportunity, he remains with the friends he has made at the ward. He becomes their leader, and pushes these mentally disabled men to realize their potential for breaking through the apathy that dully colors their monotonous lives.

The counterweight of Nicholson’s energetic and impulsive performance is Fletcher’s portrayal of the humorless, efficient Nurse Ratched. She appears villainous (especially after Billy takes his own life as a direct result of her actions), but her character is complex and ambiguous, and she can be viewed as a professional trying to hold her own and keep order in her work environment, which is dominated by men. There is even a scene in which she takes part in McMurphy’s case study, and suggests that he be kept on at the ward because she thought she could help him and did not wish to push her problems off onto others.

Not all of the scenes work perfectly. Billy’s suicide, for example, seems out of place and does not really fit with the thematic or critical elements of the film. Likewise, the fishing trip is an odd break in setting, and one which Forman was initially opposed to but unfortunately decided to include. The men had chosen to vote against watching the World Series because it would be too drastic a change from their regular schedule; it is a huge leap from the realism of the ward to the idealistic fantasy of the group escaping briefly to go fishing.

The large cast of ward members all live their roles with earnestness. William Redfield as Harding, Sydney Lassick as Cheswick, Danny DeVito as Martini, Christopher Lloyd as Taber (among others already mentioned and some not) all inhabit their unique characters, and their trivial interactions are what I feel give the movie its potency: their idiosyncrasies when playing cards; their nicknames; their perpetual arguments; the way they intentionally push one another’s buttons. It seems odd to argue for less plot, but I feel that the film could have been better if it didn’t go over the top with its violence at the end, and instead lingered on these incredibly realized and well-acted characters. Forman had the cast live in the ward, and often had multiple cameras running; he also encouraged the actors to develop their characters informally with cameras rolling, and the memorable performances are a result of those tactics.

Haskell Wexler’s camera work (also featured in Norman Jewison’s 1967 film In the Heat of the Night) resulted in the second of his six Academy Award nominations. Along with Wexler’s cinematography, Forman’s steady direction humanizes the men in the ward. In only his second English-language film (after creating several films as part of the Czechoslovak New Wave, such as Loves of a Blonde and The Firemen’s Ball), Forman’s film has endured. It is at its best when the ward members participate in jaunty comedic scenes that push the boundaries of good taste, showing themselves to be foggy representations of every person, mental illness notwithstanding, but it also has moments tenderness, vulnerability, anger, insanity… it runs the gamut of human emotions.

After a string of memorable performances over the previous decade—Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, Chinatown, among others—Jack Nicholson’s performance in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest cemented him as a unique and exceptionally talented actor, and he would go on to become one of the most well-respected at his craft. His impromptu and familiar dialogue here is worth the price of admission alone.

Though the film’s potential political and social insinuations don’t have as much to say so many years later, the direction, acting, and editing are all laudable and the result in an eminently engrossing film.

1. The other two were It Happened One Night (1934) and The Silence of the Lambs.

2. If you even want to read into it at all. It is gripping and entertaining enough with a surface reading.

Sources:

Levine, Richard. “A Real Mental Ward Becomes A Movie ‘Cuckoo’s Nest’”. The New York Times. 13 April 1975.