“No more talking. No more guessing. Don’t even think about nothing that’s not right in front of you. That’s the real challenge. You’ve gotta save yourselves from yourselves.”

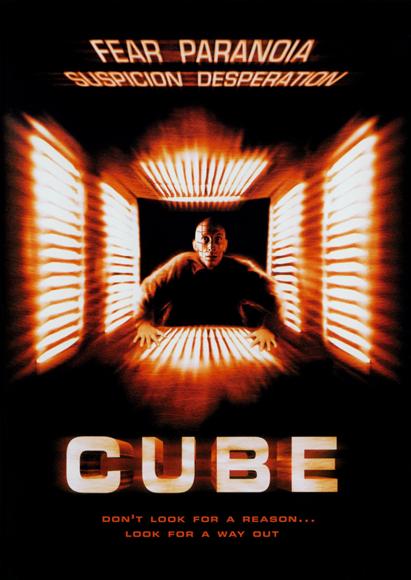

If Cube could have capitalized on its bizarre premise and memorable opening scene it could have been a great movie. Instead, it fumbles along as a fine little science fiction horror film that is noteworthy primarily for its creative production choices on a limited budget and its sustained paranoia. Director Vincenzo Natali proves extremely capable of hooking the audience with the intriguing set-up but seems uninterested in offering much of a resolution, content to dwell on the surface-level horror of the terrifying human experiment that the story is built upon. While the central premise and mathematical solution to navigating the matrix will appeal to fans of sci-fi, the jump scares and blood spatter provide plenty of cheap thrills for the horror crowd as well. While some telling signs of its cheap production hamper the film, the unique premise and gore helped Cube become a cult classic; spawning a sequel and a prequel and sustaining Natali’s career for several decades.

Inspired by an episode of The Twilight Zone (“Five Characters in Search of an Exit”), our characters wake up in a matrix of identical metallic boxes, realizing that they have no memory of arriving there. They do not know why they are there or how to get out. In each cube, there are identical doors in the four walls as well as the floor and the ceiling. They try several of them and discover that some of the rooms are booby-trapped (one of the gruesome death scenes was later copied in Resident Evil).

Each of our protagonists is named after a real-world prison and has a limited set of traits that define them. Quentin (Maurice Dean Wint) is a cop, aggressive and bossy; Joan (Nicole de Boer) is a young mathematician; Worth (David Hewlett) is a disgruntled and cynical office worker; Holloway (Nicky Guadagni) is a doctor whose main contribution to the film is her wild conspiracy theories; Kazan (Andrew Miller) is a mentally handicapped man who can rapidly perform complex calculations in his head; Rennes (Wayne Robson) is an escape artist who has broken out of a handful of prisons. Questions of why they are there and how they were chosen give rise to some interesting conjectures—they were abducted by aliens, they’re part of a government experiment—and prove more interesting than the question of how to get out.

The most Kafkaesque possibility arrives when Worth admits to having designed the outer shell of the cube structure for a faceless bureaucratic institution. It is postulated that the project had been lost in the mix of the large corporation, having changed hands and purposes so many times that it was only now put to sadistic use so as to not be “wasted” by the company. It is reminiscent of Kafka’s The Trial, a well-regarded novel in which a man stands trial against a faceless accuser for an unidentified crime.

But the film doesn’t spend very much time deliberating on the why, using the conjectures as flavorful throwaway dialogue. Instead, the film entertains through rising tensions, the smartly designed experimental device, and periodic death traps. Regarding the latter, Alderson (Julian Richings), who never meets any of the other characters, is diced by a swinging grid of razor wire in the film’s opening scene. Later, the cocksure Rennes tests a room by unlacing his boot, tethering it with the lace, and flinging it into the empty space. When he enters, believing it to be safe, he is doused in corrosive acid that melts his face.

Even though the film is only mildly successful at achieving its aims, I am drawn to it for its creative use of a small budget (only $350k) and its mathematically sound explanation for the titular contraption. Despite the team moving throughout the endless complex of identical rooms, only one of them was constructed. They used interchangeable wall panels to give the rooms different colors and filmed out of sequence to accommodate the set. Although six hatches appear (one of each side of the cube), only one was functional and able to bear the weight of the actors. By clever design and solid editing, the filmmakers effectively fool the audience into believing that these people are trapped inside of a nearly endless maze.

The constructed cube consists of 17,576 (26^3) individual rooms, minus an undetermined number that allows the rooms to constantly shift relative to one another based on a calculation involving prime numbers. The positions and movement of the individual rooms can be determined by some fancy math using the unique nine digit numbers engraved into panels in each room. I thought perhaps I was supposed to look the other way as they pulled off some illegitimate trick to navigate the way out, but the internet assures me that the concept was well thought-out by designer David W. Pravica and that any inconsistencies are results of on-the-fly changes that occurred during shooting.

When they finally find the single exit from their mechanical prison, the blinding light that greets the survivors reinforces just how claustrophobic the rest of the film is. Close-ups dominate, and the rigid right angles do not provide much aesthetic variety. Only the bold color palette serves to mix the film up visually. The effects are mostly cheap, with several notable exceptions that likely sucked up a decent chunk of the budget.

For all that Cube gets wrong, I still find myself excited by its creativity. Natali effectively establishes his themes of paranoia and isolation using only a small cast and a tiny set on a very modest budget. His subsequent efforts, from Cypher to Nothing to Splice, have all trod in similar thematic territory, but none have been quite as inventive as Cube. The obvious flaws hinder it from ever approaching true greatness, but it undoubtedly deserves its cult status.