“You know, lady, you got balls the size of grapefruits.”

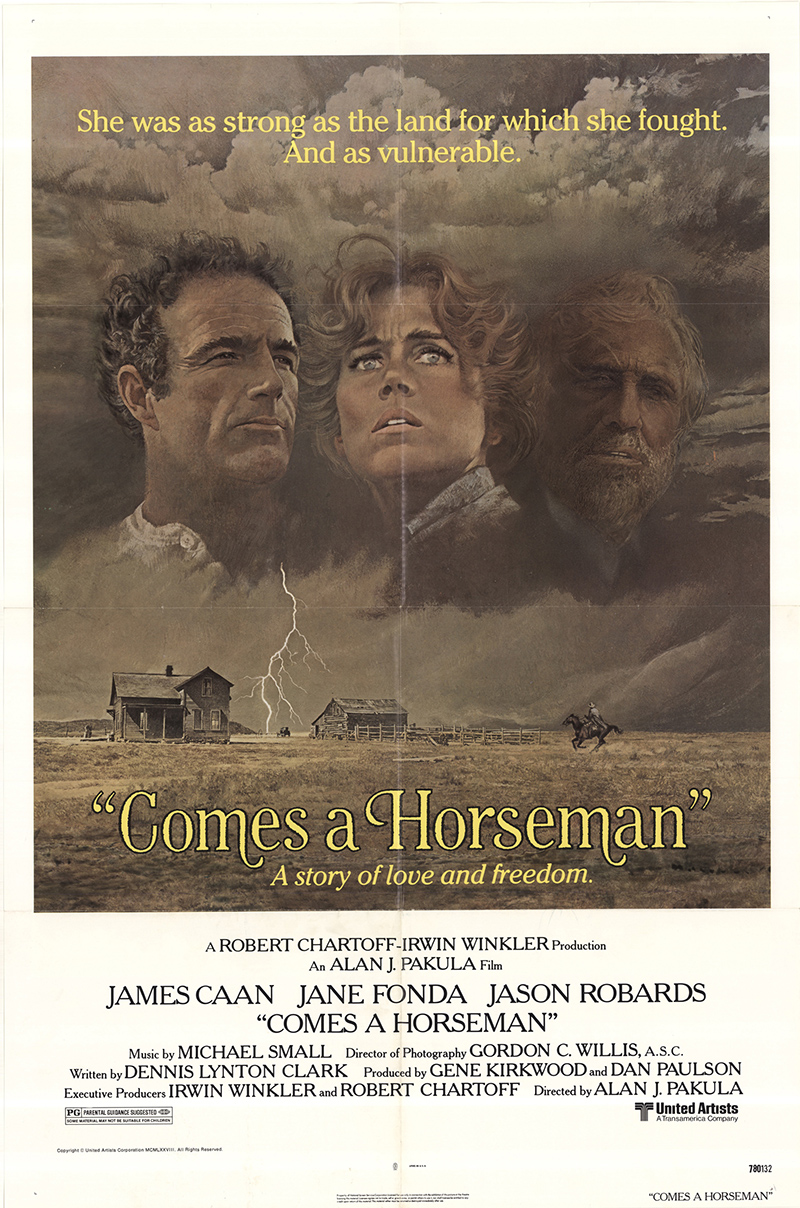

Handsomely shot and languidly paced, Alan J. Pakula’s 1940s-set Western Comes a Horseman ambles along with an intentional lack of urgency as it depicts a bygone way of life and the intrusion of industrialization upon it. A nostalgic, laconic, multiple-character study that revels in its unique setting, it approaches greatness only to fall short due to a silly, ill-fitting climax.

After inheriting a threadbare ranching operation from her departed father, Ella Connors (Jane Fonda) is forced to engage in a lengthy battle of wills with local cattle baron Jacob Ewing (Jason Robads), a former flame with greedy aspirations. With the help of an oil executive (George Grizzard), Ewing has been buying up all the small ranches in the valley and integrating them into his own massive enterprise. Ella intended to hold out just like her father—counting on nothing but grit, chutzpah, and her trustworthy ranch hand Dodger (stuntman-cum-actor Richard Farnsworth)—but circumstances force her to sell some of her land to make ends meet. Only she doesn’t sell to Ewing, but to Frank Athearn (James Caan), a recently-returned war veteran who falls in love with the gorgeous scenery, and, after a season of collaborating ranching with his new neighbor, Ella too. Complications arise when Ewing starts playing hardball and his financial backers force him to probe the valley for oil.

Conventional wisdom would suggest that Dennis Lynton Clark’s screenplay is responsible for the film’s lackluster reputation. Indeed, there’s no getting around the fact that very little happens, narratively speaking, when one considers that the film is just a tick under two hours long. Or that the wild developments in its final act feel woefully miscalculated. But taking into account the auteur-friendly era in which it was made, the considerable merits of Gordon Willis’ cinematography (there’s one shot where he beautifully captures lightning on the prairie), the weathered authenticity of Fonda’s performance, and the on-location verisimilitude of its ranching activities, it’s best to view it as a mood piece akin to Malick’s Days of Heaven. Which at least justifies its elliptical storytelling. We are supposed to feel the slowness, to savor the workmanlike rhythms of a vanished world, to contrast the heavy machinery spreading out across the virgin land with the meager tools used by the ranchers, more so than we are meant to get caught up in the machinations. Well, truth be told, way too much time is given over to those machinations for that to be the case, but it’s how I’ve decided to archive the film in my memory. I won’t remember the discussions of bankruptcy and blackmail or the generic set pieces, but I will remember the elegiac sequence that sees Dodger quietly riding off into the wilderness to die in peace and the quiet moments shared between Caan and Fonda.