“I’m not against technology, doctor. I’m against the men who deify it at the expense of human truth.”

Carl Sagan is often put forward by adherents of scientism as a patron saint of modern atheism. His skeptical approach led him to view the “sky daddy” conception of God as an unbelievable one (which is fine, because no serious person actually believes that). But neither did he cling to a steadfast belief in the non-existence of God. He merely concluded there was not sufficient evidence either way, considering our limited human capacity and narrow vantage incapable of grasping such a large concept in its totality. But he did not take his neutral position as grounds for dismissing notions of a moral system, intelligent design, spirituality, etc. that seem to be inherent in us. Instead, he simply stole those things from the God that revealed himself to mankind in history and expanded his conceptions of Science and the Cosmos to assimilate those ideas—essentially professing a belief in pantheism.

Whatever his shifting beliefs were at the end of his life, he was clearly not an atheist. He wrote a number of nonfiction books, but also authored the 1985 science-fiction novel Contact, which originated as an idea for a film and was eventually adapted to the screen by Robert Zemeckis near the end of Sagan’s life. In the film, Zemeckis and Sagan (who was very involved in the production) try to bring the religions of scientism and Christianity into tension with one another. In the process of highlighting the religious nature of science as a belief system—rather than a tool or a method of discovery—they also tell an intelligent story based on hard science and legitimate concepts, allowing them to explore ideas of meaning, existence, and reconciliation with an air of legitimacy. It’s a bold work, one with few equals considering its fusion of cerebral subject matter with high production value and engaging storytelling.

The ruminative tale of humanity’s first contact with extraterrestrials is centered on Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster), a research scientist who has staked her career on discovering alien life. Her mother died in childbirth and her father (David Morse) raised her with a scientific career in mind, introducing her to amateur astronomy and short wave radio when she was young, before he, too, passed away when she was yet a child. In an early scene, Ellie (played in flashbacks by Jena Malone) asks her father if the radio can communicate with towns and cities and planets that get progressively further away. She then asks if the radio can reach her mother—a clue that her lifelong pursuit of a signal from the cosmos is bound up with her inner struggle to make sense of her life in the wake of her parents’ deaths.

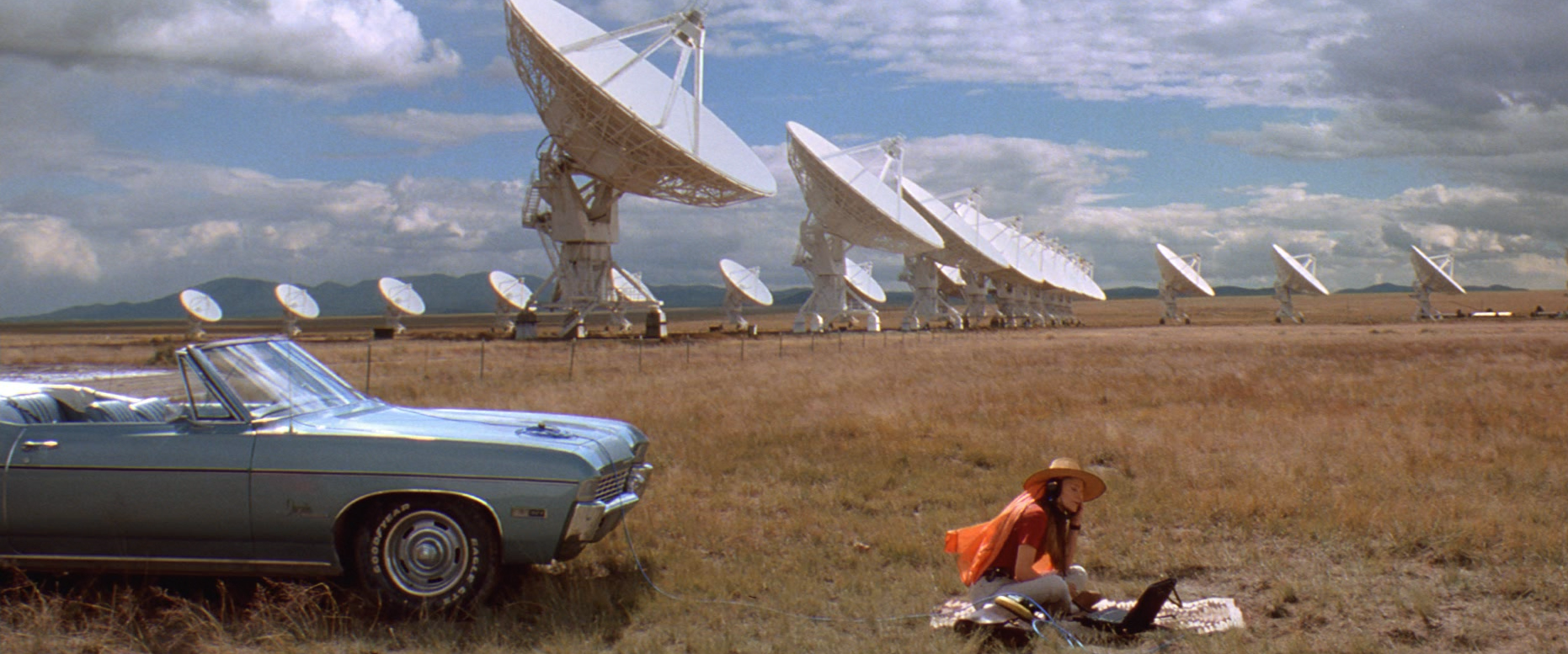

The film opens with a brilliant sequence in which the camera zooms out from the earth to display the universe in all its vastness, slowly moving through our familiar solar system before picking up speed as we back out of our galaxy and through many more. As we zoom out, snippets of radio transmissions are picked up, and as we tune into the cacophony, we realize that the transmissions are going backwards in time, until the oldest one is broadcast, followed by radio silence. This creative introduction is echoed when first contact is made. Ellie, now an adult, has excelled academically and works at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico where she controls a massive radio telescope and searches the billions of star systems for signs of intelligence. David Drumlin (Tom Skerrit), the president’s science advisor, pulls funding from the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) program, forcing Ellie to seek financial support from private sources. She has a brief fling with priestly dropout Palmer Joss (Matthew McConaughey), then moves to New Mexico to continue her work at the VLA (Very Large Array), courtesy of billionaire industrialist S.R. Hadden (John Hurt).

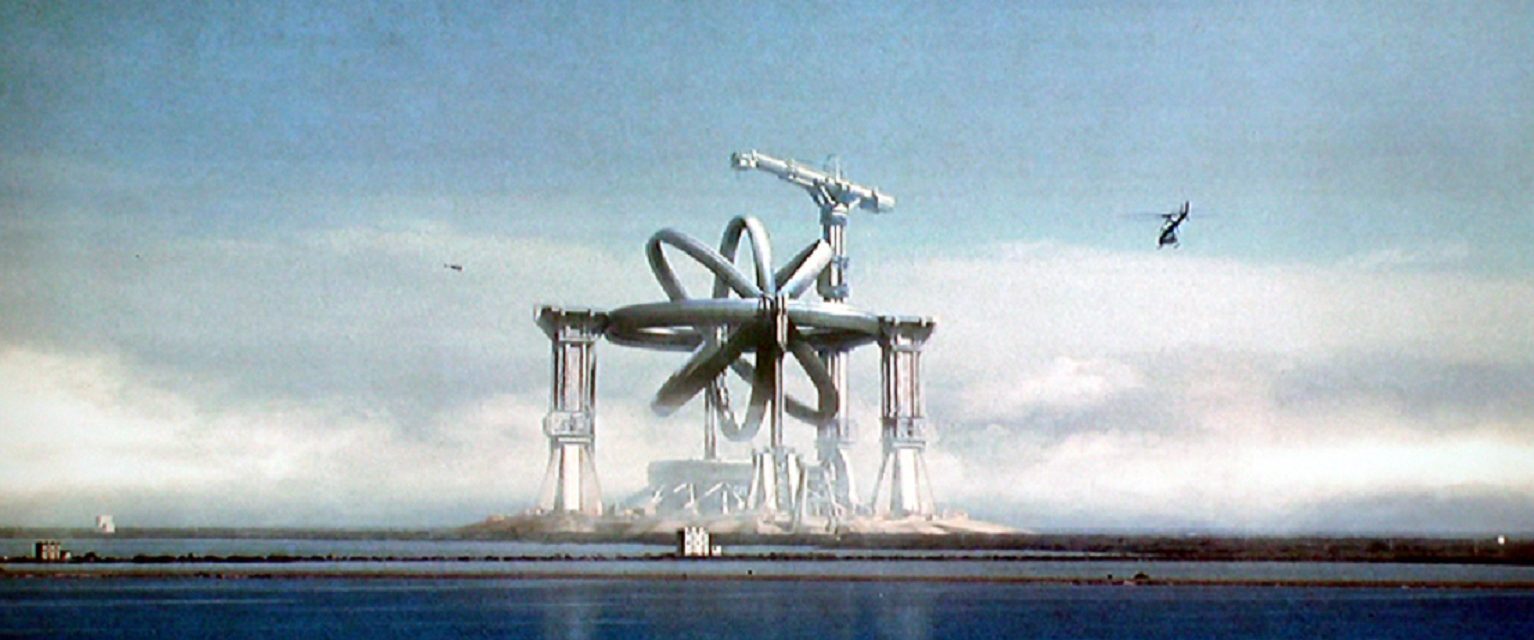

It is here, four years later, that she hears the signal. Lounging on the hood of her convertible, she drifts off to sleep, startled awake when a muted screech begins pulsing prime numbers into her headphones. In the lab, her technicians, led by the blind Kent (William Fichtner), gradually come to grips with the scope of the broadcast. At first, it appears that the signal from Vega, 26 lightyears away, is merely a series of successive prime numbers—proof of intelligence, sure, but devoid of meaning. By the time a collection of 2-dimensional drawings and a hidden video are found buried in the signal, Director of National Security Michael Kitz (James Woods), a handful of military personnel, and David Drumlin are crowded around the video monitor to witness Adolf Hitler’s opening address at the 1936 Summer Olympics. It’s a bold storytelling decision—the video is initially zoomed in on a swastika before it is manipulated to show the entire frame as Hitler begins speaking. To an unknowing audience, this moment is jarring. Is this some kind of sick joke meant to humiliate Ellie, who has put her career on the line, and, according to Kitz, potentially jeopardized national security? For a moment, the shocked silence of the observers mirrors our own dismay. But several of them are piecing together the timelines, and soon postulate that if the broadcast—the first with the strength to leave earth’s ionosphere—was immediately rebroadcast from Vega upon receipt, the redirected signal would just now be returning to earth. Once the 2D drawings are sifted through and placed in the proper sequence, it is revealed that the thousands of schematics culminate in a machine, a device that appears to be designed for a single traveler to be sent into space. Several countries collaborate to fund, manufacture, and construct the massive device, which costs upwards of $1/3T. Ellie finds herself in the spotlight, commenting on the importance of her discovery and making the case for herself to be the representative of humanity to be launched into the stars.

Palmer Joss returns to the narrative; with a bestselling book on religion and technology under his belt, he has become something of a religious authority. He’s also mysteriously allowed into every important meeting of government officials. The tense relationship between Palmer and Ellie is where the real juicy stuff occurs. Of course, for a streamlined Hollywood production, even one as considerate as Contact, there’s going to be a sacrifice of depth. This is partly to keep the narrative from getting too sidetracked, but also because Zemeckis is trying to appeal to two crowds that generally despise one another. So, while the pair engage in some piercing analyses of one another’s deeply held beliefs, we’re never presented with anything of true depth because the filmmakers are trying to get everyone to the finish line, not one particular side. There are a few elementary jabs thrown around, such as, “What if science simply revealed that God never existed in the first place?” and “Where did Mrs. Cain come from?” At one point Ellie asks Palmer to prove God’s existence, and he asks her to first prove that she loved her father. Those kinds of things may seem profound or clever to a certain crowd, but I found it much more satisfying when Ellie’s experience with extraterrestrial contact takes on religious connotations. She tries to assert that the communication was scientific in nature, claiming that if it had been religious in nature it would have come in the form of a burning bush or a voice from the sky. Palmer points out that she did, indeed, hear a voice from the sky. Since her unique experience cannot be verified, she finds herself asking the entire world to simply take it on faith that her encounter was real and not some kind of hallucination. Although it’s not dealt with explicitly in the text of the film, her single claim contrasts with the numerous eyewitnesses of Jesus’ death and resurrection, which she finds unbelievable. She states that risking her life is a noble act if it leads to even the smallest increment of progress in understanding the purpose of humanity; this parallels the Apostles’ martyrdom.

Once Ellie is strapped into the metallic orb and sent zipping through a series of wormholes to Vega, Zemeckis wisely refrains from pulling back the curtain. The mysterious is always more effective when it remains unknown, and this is achieved creatively by having the alien species read Ellie’s memories and meet her on an idyllic beach in the form of her deceased father. The visual effects on the trip and on the beach offer a subtle yet surreal departure and exemplify how to use effects for creative purposes (rather than to shortcut tough-to-shoot sequences). Although meeting her father in the stars gives a false sense of thematic closure—it appears and feels as if she’s encountering her father in heaven—it doesn’t feel as silly as I was expecting it to.

Another element that adds to the veracity of Contact is the use of vintage Bill Clinton speeches, doctored to appear as if he was addressing the topic of extraterrestrial contact. There’s a brief shot in which his likeness is rendered into a scene with James Woods and other cast members, done in grainy video footage to help mask the artifice. In many other cases, the lo-fi aesthetic is utilized as a shorthand method for conveying that certain scenes are television broadcasts. The presence of several prominent television personalities, including Larry King interviewing McConaughey’s Palmer Joss, and Jay Leno doing a monologue, provide original material for the film.

Many critics were dissatisfied with the conclusion—no slender green aliens, no firm proclamation on the central debate, no clear evidence to determine if Ellie’s journey was real or simply a mental excursion. I think it’s fantastic. It presents both a Christian man (albeit one who thinks that one night stands are morally acceptable) and a staunch atheist as possessing intelligence, compassion, and empathy, who are able to support one another despite their differing beliefs. Zemeckis, dependably handling the effects, puts to celluloid one of the most thrilling trips through space since 2001, and otherwise directs with a steady hand. Most importantly, the central tension of the question of God’s existence is not treated superficially, but is actually integral to the plot. The story is carefully built in such a way as to examine the question and portray the results of extremism in both directions without kneecapping itself with too many frivolous asides or polemic diatribes. The authenticity of the research and space flight is bolstered by bona fide science grounding the entire thing, with the eccentric billionaire S.R. Hadden being the sole cause for incredulity (even though Hurt’s performance is a lot of fun). And crucially, Zemeckis and his regular editor Arthur Schmidt manage to retain the sweeping blockbuster narrative pace that truly evokes senses of awe and wonder that arise from contemplating the immensity of the universe, regardless of one’s beliefs.