“If I don’t draw for a while, I get really crazy. I start feeling really, like, depressed and suicidal, if I don’t get to draw. But then sometimes when I’m drawing, I feel suicidal too.”

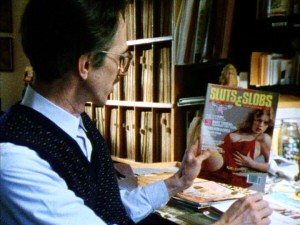

The general theme of Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb, and possibly of its subject’s life, is impeccably summed up by pornographer Dian Hanson. “He has told me that he masturbates to his own comics,” she says, referring to underground cartoonist and musician Robert Crumb. Contained within that simple phrase is the artist’s acceptance—nay, embrace of his depravities, and his total lack of inhibition, but also his unwavering sense of individualism and belief in freedom of expression. All of these notions and more have been explored throughout the years in the artist’s trademark style, with all its erratic lines and nausea-inducing density.

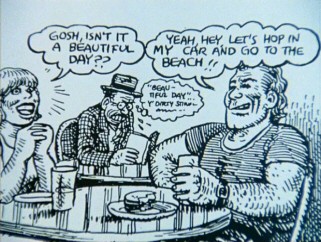

Raised with two brothers who never managed to transcend the Oedipal struggles of their adolescence, Crumb forged his own path in life by accepting his natural introversion and perverted impulses and channeling them into cartoon drawings. He did commercial work, but the lifelong passion that saturates Zwigoff’s documentary is his use of the comics medium for spontaneous self-discovery and subconscious social criticisms. There are no messages, per se, in these peculiar, unmistakable works, which depict a sort of quaint, idealized early-mid 1900s America laced with contemporary social issues and surreal debauchery, but they are dripping with text and subtext that cry out for interpretation, some of which Crumb retrospectively provides without a scintilla of mortification. In fact, he’s almost gleeful as he reveals sketches he’s made as a middle-aged man of a cross-eyed farmgirl he admired as a schoolboy, or when he explains strips about a headless sex slave and a picturesque ‘50s nuclear family plagued by incest. “I had some vague idea that it meant something,” he says, referring to a strip in which the hearts of African-Americans are canned and sold in supermarkets under a provocative name, “but it was only later that I’d look at it and kind of analyze it and see what it’s about.” At one he points he recalls a sexual awakening triggered by Bugs Bunny.

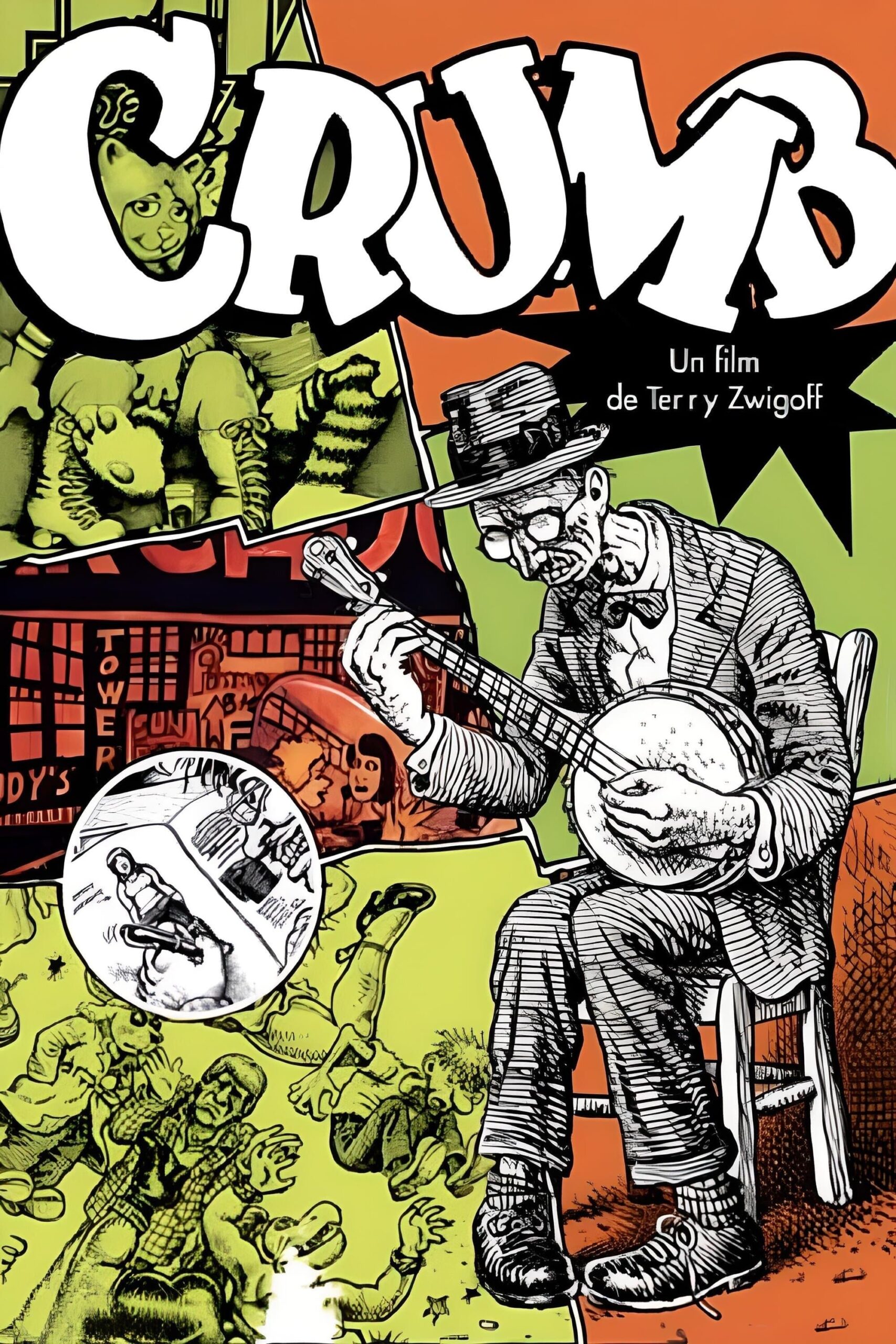

As the film begins, Crumb is seen giving a lecture to some art students. He quickly rifles through projector slides of his best known work—the Fritz the Cat comic strip, the oft-imitated Keep on Truckin’ drawings, the cover of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills—then dismisses these minor cultural landmarks as victims of a horrible commercial system that swindled him, mutilated his art, and reduced his extremely rich and extensive body of work to a few trifling icons. Beyond this introductory segment, there’s very little coherent structure to the film as it deep-dives into the illustrator’s creative process, his eccentric lifestyle, and the strange environment he inhabits. It bounces around eras and locales, shifting from biography to commentary, achieving a flow that could only have come from extended rumination on the material.

What it comes down to is that drawing is as essential to R. Crumb’s continued existence as breathing is for the rest of us. He is at home only among his sketchbooks and old ragtime and blues records. When he reviews sketches, he’s able to pinpoint his psychological states and the external factors that were influencing him, giving a firsthand account of how various motivators (sex, art, love, hate, politics, family, religion) all mingle and take on a mongrel life of their own. In one incredible segment his ex-wife sits next to him, flipping through a sketchbook in which each had drawn pictures of the other. A few pages later there are new sketches of another woman and another woman’s sketches of Crumb; the other woman is Crumb’s second wife, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, a revered cartoonist in her own right. This is a man totally given over to his id’s wildest impulses, who also happens to have a pinch or two of artistic genius in his DNA.

Elsewhere, talking heads debate the virtue of his popular work—is it worth trying to look past its pornographic, misanthropic surface to perceive the satire and psychological rumination below it? One critic likens him to Brueghel—but the most eye-opening element of the film is its examination of the Crumb family, especially the boys’ early life. Brothers Charles and Maxon are both artists, but neither was able to overcome their rough upbringing in the way that Robert did. Charles was a gifted storyteller in his youth, obsessed with Disney’s Treasure Island and boasting a developed cartoon style at an early age, who now lives as a drugged-up depressive (and killed himself after Zwigoff finished filming); though he’s on screen for only a small amount of time, his presence dominates the film—a sedated ghost of a man who’s potential future is nothing but living in the past. Maxon (who gained some traction as an artist after the film’s release) combatted his predatory sexual desires through self-administered yogic body cleansing techniques. Both of them share Robert’s uncanny lack of shame in speaking about their morbid sexuality shaped by the twisted fantasy worlds they created to escape their traumatic home life. This looking back provides context and nuance to Crumb’s art, which taken at a glance can often be perceived as severe and repellent.

Like Gimme Shelter, Crumb is a brilliant, non-judgemental exploration of the dark underbelly of the New Age ethos; an observational presentation of a jumbled, scuzzy lifestyle in which twisted sexual desires, unchecked drug use, and poor parenting exacerbate the natural depravities of mankind. But none of these people, as socially outcast and deeply odd as they seem, appear any more naturally-inclined toward evil than the rest of us. In fact, despite every sobering anecdote we hear, the members of the Crumb family remain amiable, warmhearted, and terribly funny. It’s a truly disarming film, better at humanizing the hillbilly outsider raised on tainted pop culture and TV dinners than any scholarly treatise could hope to be.

One of the achievements of Zwigoff’s film is that it refrains from venerating its subject. Robert Crumb liberated himself from his harmful upbringing through his art while his brothers did not—a bona fide triumph of the artistic spirit—but situated next to them, he is another damaged weirdo who doesn’t really fit into mainstream society. Nevertheless, even as he mostly just wants to be left alone to do his own thing, through the power of art he was able to forge a connection to the wider world, and he has flourished in his own way. Crumb not only presents a complex artist who cannot be quickly assessed, but raises questions about the very nature of art and art criticism in modern America.