“One doesn’t choose the time one gets into trouble.”

It’s understandable that some people have trouble assessing Polanski’s works. Some find it necessary to view every new project through the lens of the death of Sharon Tate, while others cannot mentally consider the man’s work without thinking of the criminal allegations against him.

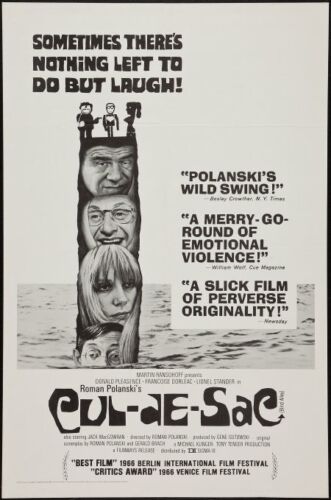

Before the Polanski discourse became log jammed by discussions of consent and the Manson Family, and his lesser known early films became dwarfed by the reputation of his later masterpieces, the director was pumping out some really solid work. After two winners to begin his career, he embraced his weird side for his third—the absurd, meandering, indecipherable Cul-De-Sac. Here Polanski is exploring themes that would become familiar throughout his career: isolation, regret, sexual frustration. It doesn’t rank amongst the director’s greatest films, but if it’s approached as an absurdist comedy—indeed, the comedy is the film’s saving grace—rather than the dramatic thriller that it is easily mistaken to be, the sad and amusing story can be appreciated to a certain degree.

On a remote island accessible by road only when the tide is out, a mismatched couple are occupying the magnificent Lindisfarne Castle when a criminal duo invade their property. Gut-shot during a bungled robbery, one of them soon dies, leaving the other to fend for himself. The movement of the tides and the late hour dictate that the trio become trapped there together, distrusting one another but forced to collaborate. The majority of the film, like Knife in the Water before it, focuses on three principal characters—the bored, sexually unfulfilled Teresa (Françoise Dorléac); her pathetic, cross-dressing husband George (Donald Pleasence), and gruff American gangster Dickey (Lionel Stander).

Dickey’s criminal nature is evident in his actions and mannerisms, but we never learn much about his past. Early on, he calls a mysterious figure named Katelbach, makes plans to be picked up from the island, and then cuts the cord to prevent either of his hosts from phoning the police. But Katelbach never arrives, and instead, we bear witness to the strange relationship that develops between these three people. And it gets strange indeed—e.g. the gangster forces the couple to dig a grave for his fallen partner, then they hold a wake on the beach, where the gangster and the effeminate man get drunk while the promiscuous wife swims in the nude, then the gangster shoots at a passing plane because he initially thought it was Katelbach coming for him in a helicopter and is upset that he was wrong.

The plot shambles along in chaotic fashion, moving between genres on a whim, from thriller, to horror, to comedy, to emotional drama. We sense some tension at various points, like when Teresa escapes from the couple’s locked bedroom in the middle of the night only to approach Dickey—who is burying Albie (Jack McGowran)—with a bottle of vodka and two glasses, or when George consistently fails to stand up for himself or his wife. But this tension is almost always undercut by some odd attempt at humor. Polanski’s funny bone is crooked and peculiar and doesn’t often provoke laughter, but it is amusing nonetheless and only suffers because it is not integrated all that well.

Thankfully, the performances by the three leads are all strong. Pleasence, especially, is very good as the cross-dressing madman. His proclivities and writer’s block hint at some deeply buried turmoil that he refuses to address that almost comes to the surface during the wake on the beach when he sits on his knees and begins rambling to Dickey. Ultimately, the three main characters in Cul-De-Sac are all dealing with personal problems that do not stem from the situation that we witness. They each bring their own troubles into the ordeal and struggle with personal agitations while going through the bizarre motions of the familiar hostage scenario. It’s a complex web of themes to try to hold together, and Polanski fails to do so successfully, leaving us with a baffling little arthouse psycho freakout that is challenging to grasp.

While it fails to stir narratively, Cul-De-Sac has a very strong, if warped, personality, ruminating as it does on themes of emotional and sexual humiliation. One must concede its boldness and atmosphere, but aside from a few novel flights of fancy, it doesn’t stack up particularly well next to the director’s other work from this early era (except for The Fearless Vampire Killers, which is awful). It has the stark look and texture of something that could have been very good, thanks in large part to its unique setting and the lens of Gilbert Taylor, but there’s a reason this one isn’t mentioned alongside Polanski’s best works.