“Deep in the human unconscious is a pervasive need for a logical universe that makes sense. But the real universe is always one step beyond logic.”

Frank Herbert’s Dune is a culmination of many of the things that make science fiction great, and it is one of the enduring classics of the genre; a touchstone for many current authors and a benchmark against which any new contenders must be measured. The book is the first of six in the original series. But while the remaining books contain many strong elements and have their own unique merits, they all rely heavily on the preceding volumes. As such, the first book is uniquely readable as a standalone (which some would recommend), and as such is a magnificent, self-contained, work of art.

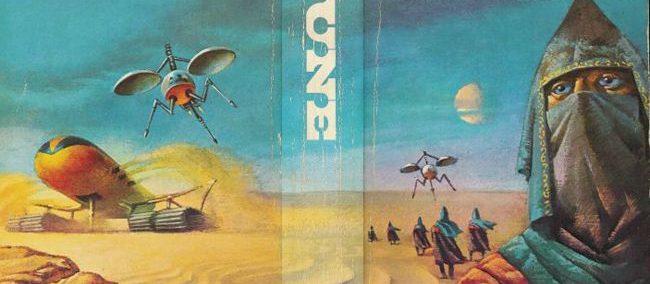

Like the best sci-fi and fantasy, Dune drops us into fully-realized universe, complex and intricate just like our own. In the indigenous Fremen, Herbert presents a unique culture that is shaped by the harsh conditions of their environment on the desert planet of Arrakis. The Fremen conserve water by wearing stillsuits (garments that collect and recycle the moisture from their bodies), and live in sealed dwelling places. It is a great display of honor to cry at the death of another as water is such a precious commodity.

Set thousands of years into the future, mankind has populated the galaxy, and technology has advanced rapidly. There are energy shields, ornithopters, lasguns, and of course, spaceships. Entire planets and cultures are dedicated to technological innovation. 10,000 years before the events of the novel, a crusade was launched against robots and other thinking machines. As a result, the Orange Catholic Bible, the primary religious text of the Dune Universe, contains the commandment: “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.” This element makes Dune and its sequels stand out in a genre crowded with robots and supercomputers. Herbert’s world feels more organic and depends upon humanity’s physical and mental capacities to drive the plot.

Several groups have pushed the development of human abilities in lieu of computers. The Bene Gesserit—a quasi-religious sisterhood—manipulates the evolution of humanity on the scale of millennia through social engineering and eugenics. They are psychically advanced and physically skilled; they can read minds, negotiate, and fight, and are so advanced in their tactics that some consider them witches. The Bene Tleilax have mastered biological manipulation. They can create gholas (clones) of human beings from only a few cells, and have developed the art of “face dancing” which involves a human temporarily taking on the form and personality of another human. Mentats are humans trained from a young age to function as data analysis machines—they receive data inputs, and calculate solutions to problems. The Bene Tleilax are known for creating “twisted” versions of mentats that are able to compute free of ethical restraints that were ingrained in them during their training. The Spacing Guild makes use of Navigators, which are mutated humans with advanced psychic awareness that allows them to guide space travel at light speed.

On Arrakis, several different ruling families have had turns governing the planet and managing its operational function as the sole exporter of the mysterious spice called melange. The substance has myriad effects—the Sisterhood of the Bene Gesserit depends on the spice’s prolongation of life; its entheogenic properties are used by both the sisterhood and the Fremen to initiate clairvoyant trances; and the Spacing Guild relies on the spice-saturated navigators with heightened awareness and prescience to guide the highliners through cosmic space-time safely. Still, many others are simply addicted to the habit-forming substance.

Indeed, the spice is not without side effects. Aside from the innocuous darkening of the eyes to a deep blue, the drug is very addictive. The navigators, who live in a tank filled with a cloud of spice-gas, see their bodies gradually mutate (see David Lynch’s film adaptation, where a Guild Navigator looks like a grown-up version of the malformed infant in the director’s feature-length debut, Eraserhead). Paul Atreides—the son of the royal family that is assuming control of Arrakis as the novel begins, and the primary protagonist of Dune—describes the spice as a “poison—so subtle, so insidious… so irreversible. It won′t even kill you unless you stop taking it. We can’t leave Arrakis unless we take part of Arrakis with us.”

From the outset, the reader understands why many would covet the source of the spice. Think of it like some combination of cocaine and crude oil that is also religiously significant, that could only be found in one place on earth, and then you will understand why tensions are high. However, because Arrakis is covered in desert, where the inhabitants jealously guard and conserve their water—even to the point of unflinchingly harvesting water from their dead—those in power, used to high-class living, are hesitant to make Arrakis their home planet. At the start of the novel, the Harkonnen family has ostensibly given up in their efforts to tame the desert and its savage people, and its governance has been forced upon the Atreides, who must leave their home planet of Caladan.

Herbert does a wonderful job of gradually pulling back the veil on the mysteries of Arrakis and the Dune universe in general, be they mythical, ecological, or cultural. Once we have been exposed to several of the effects of the spice, we learn of the organic ecological system that produces it. To harvest the melange, workers must tread lightly and erratically because the desert sands where the spice is found are guarded by sandworms: slithering colossi that swim through the sand like whales in the ocean. These worms own the desert, and respond to any signs of life, devouring all in their path; and so obtaining spice is both extremely dangerous and extremely profitable. The worms are nearly indestructible and in fact produce the spice as part of their natural lifecycle.

Then he heard the sand rumbling. Every Fremen knew the sound, could distinguish it immediately from the noises of worms or other desert life. Somewhere beneath him, the pre-spice mass had accumulated enough water and organic matter from the little makers [baby sandworms], had reached the critical stage of wild growth. A gigantic bubble of carbon dioxide was forming deep in the sand, heaving upward in an enormous “blow” with a dust whirlpool at its center. It would exchange what had been formed deep in the sand for whatever lay on the surface.

The Fremen exhibit a religious reverence toward the larger sandworms, believing that their actions are a form of divine intervention. In the Dune Universe, religion is deviously manipulated in order to assert control of the people, yet it is also what revolutionizes society. The great war that led to the abolishment of thinking machines and the ecumenical unification of the galaxy’s main religions has given the galaxy extended official peacetime; and monotheistic religions are cast in the negative light of conflict and zealotry. However, Herbert is aware of the role of ritual in the construction of hierarchical societies.

Soon after arrival on Arrakis, where his family has assumed governance, Duke Leto Atreides and his son Paul visit a spice-mining operation with the planet ecologist, Dr. Kynes. Kynes, aware of the messianic Fremen legends and the Bene Gesserit breeding program, is intrigued by Paul’s abilities and is impressed by Leto’s choice to forfeit a haul of spice and rescue all of the crew members when a mobile spice factory is destroyed by a giant sandworm.

Duke Leto is then betrayed and killed. The Harkonnens withdrawal from the nexus of spice production (and so a firm grip on political power) was a ruse to aid them in being rid of their rival. Leto’s concubine Jessica and their son Paul escape into the desert and find sanctuary with the indigineous Fremen. Jessica, an initiate of the psychically powerful and all-female Bene Gesserit school, has trained Paul throughout his life in the mental and physical conditioning she had learned at the school. She intends that Paul will fulfill the Bene Gesserit prophecy of the Kwitsatz Haderach: a male version of the mentally transcendent Bene Gesserit.

The novel begins with a test: a Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother, Gaius Helen Mohiam, subjects Paul to a test of humanity. She places his hand into a small box while the gom jabbar—a poisoned needle—hovers in her hand, ready to plunge into Paul’s neck if he pulls back his hand. Jessica guards the door to ensure the test remains uninterrupted. The box creates painful sensations in Paul’s hand, and his instinct tells him to withdraw it. He is free to do so, but knows what will happen the moment he does. He recites the Litany Against Fear that his mother had taught him:

I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.

He passes the test, which proves that his awareness rules his instinct; he is human, not merely animal. Jessica, hopeful that she has produced the Kwisatz Haderach, ensures a strict training regimen for her son, teaching him many of the lessons she had been taught as an acolyte of the Bene Gesserit. Paul is also taught by his father’s men—weapons masters Duncan Idaho and Gurney Halleck. Duncan served as Leto’s ambassador to the Fremen, but was killed defending Paul and Jessica as they escape during the Harkonnen attack. Halleck survives the attack, and falls in with melange smugglers.

As Paul and Jessica are hiding in the desert after Leto is killed, Paul experiences his first prescient vision. He reveals to Jessica that she is pregnant, a secret she had kept even from her Duke, and that Jessica is the daughter of Baron Vladimir Harkonnen—the man responsible for Leto’s death—which had been a secret the sisterhood kept from her. His prescience also reveals that he is the product of Bene Gesserit breeding program designed to reinvigorate humanity; however, he sees that the rejuvenation will take the form of a holy war led by the remaining Atreides soldiers and the Fremen.

When Paul and Jessica are wandering in the desert, among the first group of Fremen they encounter is their leader, Stilgar, as well as a young girl named Chani, who will go on to become Paul’s concubine. Although the initial encounter is tense, the Fremen eventually accept them. Paul’s careful upbringing, from the rigors of his mental training to his combat skills, gives him the appearance of echoing the legend in the lore of the Fremen of their prophesied savior.

Jessica and Paul learn much about the Fremen way of life; they share the desire—instilled in them by the ecologist Kynes—to see the planet transformed into a lush paradise. For this purpose the Fremen bribe the Spacing Guild with extra spice to prohibit the Harkonnens from using satellites to spy on the Fremen activities, and keep their true power and resources hidden from authorities. Aware of Jessica’s advanced physical and mental prowess, Stilgar knows he must find an official role for Jessica in the Fremen society lest the people wish for her to replace him, and so he indicates the need for a new Reverend Mother as the one in service of the Fremen tribe is growing old.

To become a Reverend Mother, Jessica must consume the Water of Life, a melange concoction. The ritual is traditionally reserved for Bene Gesserit acolytes—all female—in order for them to unlock their ancestral memories and become Reverend Mothers. When Jessica partakes of the Water of Life, she must focus inwardly to neutralize the poison she has consumed. She becomes trapped within herself, until the dying Reverend Mother of the Fremen comes and allows herself to be absorbed into Jessica’s consciousness, and with her the entire memory of the Bene Gesserit and much of human history. Jessica is pregnant with Paul’s sister Alia when she undergoes the spice agony, and thus Alia is born with a depth of knowledge beyond her years.

Later, Paul also undergoes the spice agony, after he has integrated himself thoroughly into the Fremen culture. He has learned to ride sandworms, and has become a respected warrior and religious leader. The tribe wishes him to challenge Stilgar for leadership of the tribe; however, he chooses to remain Muad’dib (which means mouse, a desert creature the Fremen deem wise), while also making his claim as the rightful Duke of Arrakis. When Paul consumes the Water of Life, he remains in a coma for three weeks. Until Paul, every male to consume the Water of Life had died in the attempt; yet, the Bene Gesserit are unable to access the male ancestors in as they do the female. For this reason, they have focused their efforts on their breeding program in hopes of producing a male Bene Gesserit. After he passes through the internal trials it brings, he is able to commune with the memories of both male and female ancestors that now populate his mind; he has become the prophesied Kwisatz Haderach.

When Paul awakens from the coma, he is aware of things previously unseen. He is able to sense the imperial ships that are orbiting the planet, and beginning to descend on it. This sets up a climactic final scene in which Paul is able to force Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV to cede the throne to him, by threatening to destroy all of the melange left on the planet and notify the Landsraad (a galactic council of noble houses) of Shaddam’s involvement in the Harkonnen betrayal of the Atreides family.

Each chapter in Dune begins with an epipgraph written by the Princess Irulan, which serve to set the tone and fill in little bits of backstory, substantially fleshing out Herbert’s complex universe. Through her writings, we understand that though her father—the Padishah Emperor of the Known Universe—admired Duke Leto, he ultimately viewed him as a threat and aided the Harkonnen attack by supplementing their troops with his ruthless Sardaukar soldiers. We finally meet Irulan when she accompanies her father to Arrakis in the final portion of the novel. One of Paul’s demands of Shaddam is that he give his daughter to Paul in marriage, legitimizing his claim to the throne.

Dune endures because it excels at integrating a cornucopia of interesting ideas into a seamless whole, without force feeding the reader and actually encouraging them to develop their own thoughts on the subject matter (not on the fictional world, but the actual ideologies and philosophies that are presented). Frank Herbert was working as a freelance journalist in the late 1950s, covering a US Department of Agriculture initiative to control the movement of sand in Oregon by introducing new grasses to the region, when he became interested in the concept of ecological engineering. He never published his article, but instead used his research into deserts and desert people to write Dune. The book was overly long for its era, and while it won both the Hugo and Nebula awards, it took several decades for it to cement its status. However, it has longevity because there is little novelty or gimmick in it. He had done his research on the planetary transformation, and wrote from a knowledgeable vantage.

In addition to his research into deserts, Herbert had interesting and thoughtful political beliefs that informed his writing. A strong libertarian stance is evident in the Fremen’s distrust of authority; they guard their privacy fiercely, are extremely self-reliant, and lethal in combat. Herbert was concerned with the ramifications of an overly systematized government and the loss of individuality. As Dr. Kynes (a probable surrogate for the author) postulates: “The human question is not how many can possibly survive within the system, but what kind of existence is possible for those who do survive.” However, Herbert was not entirely in favor of a hands-off, individualist approach. The Fremen choose to enact the overhaul of their planet’s ecology as a grassroots movement, essentially, yet they still have customs and rules that govern themselves—their water belongs to the tribe, and only the fittest survive, where fitness is defined as usefulness to the tribe.

But these revolutionary changes to the entire world would not be believable if the people responsible for them were passive and lackadaisical. The characters must take risks, and be brave, and by taking action they themselves will be changed. Here Herbert took a number of influences and threw them into a melting pot, with an uncertain yet intriguing result. A plethora of Arabic words were inserted into the Fremen lexicon—Shaitan, bourka, aba, jihad, etc.—and they espouse many elements of Zen in their belief system. The Fremen await an eschatological messiah figure, yet this is partially undercut by the possibility that the Bene Gesserit (responsible for millennia of eugenic programming) may have planted the seeds of these prophecies hundreds of years prior as a form of social engineering and cynical religious manipulation. Their belief system is colored by ritual and superstition, and many actions with potentially secular benefit are taken based on these beliefs.

Herbert spent a lot of time digesting the ideas of different schools of philosophy and psychology, and was friends with the famous Episcopal priest turned Eastern mystic, Alan Watts. Many belief systems are woven into the narrative without overshadowing it, and it is hard to tease out exactly which of those Herbert actually held to. Clearly the use of mind-altering substances as a pathway to enlightenment is there, on the surface. But also present is the Jungian collective unconscious—the idea that part of our unconscious mind is formed not by our individual experience but by ancestral memories and experiences that are shared by all people—in which instinct and archetypes populate humanity’s collective unconscious. We see this in the Bene Gesserit literally sharing their ancestors’ memories, in the collective belief systems of the Fremen, and in Paul’s gradual fade from individual, physical, messiah to a sort of mythological figure ingrained in the Fremen tradition.

I would recommend Dune to anyone. I first tried to read it when I was in eighth grade, and I loved it, though I ended up stalling out on the second book, Dune Messiah. I read the first novel again for a project as a high school sophomore, and loved it even more because I understood more of the political interactions in the novel; in other words, I liked the talking instead of just the action. During my college years, I decided to commit to making it through all six of Herbert’s original novels, and I was able to grasp some of the philosophical and religious overtones. This, the fourth time I have read Dune, it reads as nearly perfect. From a selfish perspective, it basically takes a Pareto of all the disparate subjects that interest and influence me and presents an extraordinary, engaging, and cohesive story about all of it.

Is it alright to reference part of this on my page if I post a backlink to this page?

Nice review. Do you provide an RSS feed?