“I am a man who likes talking to a man who likes to talk.”

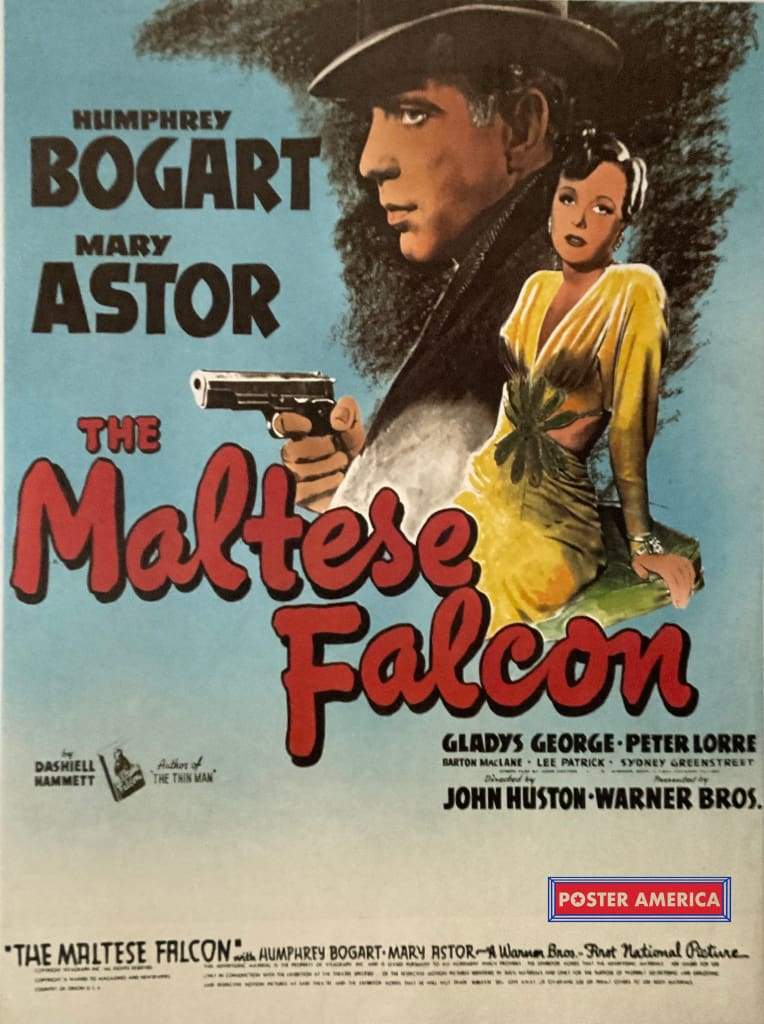

Film historians can continue to debate whether or not The Maltese Falcon was the first film noir (it was not). Likewise they can keep arguing over the late great Peter Bogdanovich’s assertion that it was the “first great detective movie.” But order of appearance only matters so much in the grand scheme of things. Even if it does not represent a turning point in American cinema, even if it did not inaugurate a genre, and even if its influence is not so great as some critics might once have claimed, it cannot be denied that John Huston’s directorial debut is a work of superlative quality on every front.

It unfolds with a churning intensity. The performances, the snappy writing, the arrhythmic editing, and the cinematography are all aimed at creating a sense of pervasive unease. For fans of engaging cinema, it’s an edge of your seat experience, even though the bulk of the film consists of talking and its moments of action are unconvincing. For students of film, it doubles as an object lesson in the use of filmmaking technique to tell a story, as the viewer is drawn in by the low camera angles and high-contrast photography, prodded forward by the jagged shadows that slash across every interior room, and constantly knocked off balance by the frequent close-ups and rapid-fire dialogue.

Interestingly, the anxious tension that those techniques give rise to doesn’t exactly jibe with the demeanor of our protagonist, the unflappable, ruthless private eye Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart). Even his fast-talking cadence, barely slower than an auctioneer, is at odds with his stoic approach to his life and profession. Distinguished from contemporary movie detectives by his lack of means, cynical attitude, and unwillingness to cooperate with the police, Spade is an archetypal antihero. He lives by a code, but it’s not a righteous one and he’s willing to compromise on it whenever it suits him. He prefers not to carry a gun, but proves familiar with their handling on numerous occasions. Money and sex seem to sway his judgement quite easily as well.

Indeed, as the film opens he decides to take on a client with a flimsy cover story because she is willing to pay him exceptionally well for a simple service. When his partner is murdered while tailing the target, Spade observes the crime scene impassively then arranges to have the deceased’s name removed from the office signage. He’s been having an affair with the man’s wife (Gladys George), who believes Spade killed her husband so that they could be together, a sentiment echoed by the two detectives (Ward Bond, Barton MacLane) who question him. But even though Spade shows no remorse and denies his involvement, his ethical code demands that he track down the killer. Or maybe it’s just in his professional best interest to do so; after all, what’s a private eye who can’t find the man who killed his partner going to do for you?

If Spade doesn’t exactly seem like a virtuous character, that’s because he’s not. But neither are the other dramatis personae that inhabit this seedy world of shadows and spies—excepting, perhaps, Spade’s secretary, Effie (Lee Patrick). The rest of them are after what amounts to maybe the biggest MacGuffin of them all: the maltese falcon, an artifact of incalculable worth, supposedly made of gold and encrusted with jewels then covered in black enamel to disguise it. Spade tracks down his client, Brigid O’Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), and soon becomes entangled in the quest for the priceless statuette along with the debonair Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), the towering “Fat Man” Kaspar Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet), and the hotheaded muscle Wilmer (Elisha Cook, Jr.), correctly intuiting that finding the mysterious object will exonerate him of any wrongdoing in the murders that start to pile up around him.

The main performances are all top-notch, from Lorre’s foppish psychopath to Greenstreet’s arrogant raconteur, but most compelling are Astor and Bogart. Astor initially appears to be an overly melodramatic conwoman, transparent in her game. But then you realize that the hollow histrionics are part of the character’s performance; that Astor is portraying Brigid as a spotty actress whose layered manipulations are only revealed as the plot shakes out. Later still you realize that Brigid only thinks she is some sort of brilliant puppet master but is actually in way over her head, at which point she becomes truly desperate, making Spade’s rejection of her even more savage. The chief pleasure of The Maltese Falcon—once the viewer has attuned themselves to the narrative complexities—is in allowing its heartless personalities to rip into each other. This verbal sparring is anchored by Spade, who, even though he constantly finds himself staring down the barrel of a gun, always seems collected and nonchalant, likely because he’s indifferent about his own wellbeing and longevity. Even in the face of death, he’ll call any woman he crosses paths with “honey,” “angel,” or “precious.” Bogart’s quick quips and apathetic mannerisms fit Spade to a tee, and his performance transformed his career from a third-billed B movie villain to a popular leading man.

The Maltese Falcon was the first film from John Huston, who’d made a name for himself by penning scripts for the likes of William Wyler (Jezebel) and Howard Hawks (Sergeant York). His long term aim was always to direct his own films, and when his screenplay for High Sierra led to another hit, Warner Bros. allowed him great creative freedom provided he made the film with a B movie budget. He decided to adapt a Dashiell Hammett novel that had already seen two inferior film versions in the ten years since its publication—a bold choice that only a supremely confident first-time director would make. In service of his vision, Huston storyboarded the entire film and sketched out a number of tricky shots that support the dynamics at play while exploring and partly establishing a new visual style.

The film is so tightly orchestrated by Huston, and so delectably layered with wily energy from the performances and restlessness from the cinematography, that its narrative slightness becomes a moot point as it is elevated into the realm of sheer entertainment. Regardless of what it progenated, it remains appointment viewing.