“Your orders are to wait for me to give you more orders.”

It is perhaps too easy to write off the entirety of Michael Cimino’s post-Heaven’s Gate career as a series of failed comebacks. In just a few short years, his star had risen and fallen in meteoric fashion, from winning multiple Oscars for his work on The Deer Hunter to washed-up industry pariah; from exciting up-and-comer to has-been. In the wake of his massive flop he was considered a former visionary stunted by his own misguided hubris. Even though his studio-bankrupting epic Western has been rehabilitated in recent years thanks to Criterion’s lengthy director’s cut, the man’s reputation and artistic mojo never recovered and his subsequent output has rarely been taken seriously.

During this post-Heaven’s Gate tailspin era, Cimino’s would frequently accept a new project and pour his undying energy into it for years on end, only to find himself at loggerheads with executives when it came time to hand over the finished product. No longer seen as the inspired genius who could demand carte blanche and final cut, he would be overruled, his eccentric vision mutilated beyond recognition and released to an indifferent public and a shrinking audience of critics predisposed toward ridicule. Regrettably, many of his most grievous wounds appear to have been self-inflicted—or at least self-caused—with many cast and crew members remarking upon his unfortunate combination of compositional genius and childish egotism that made him a troublesome collaborator.

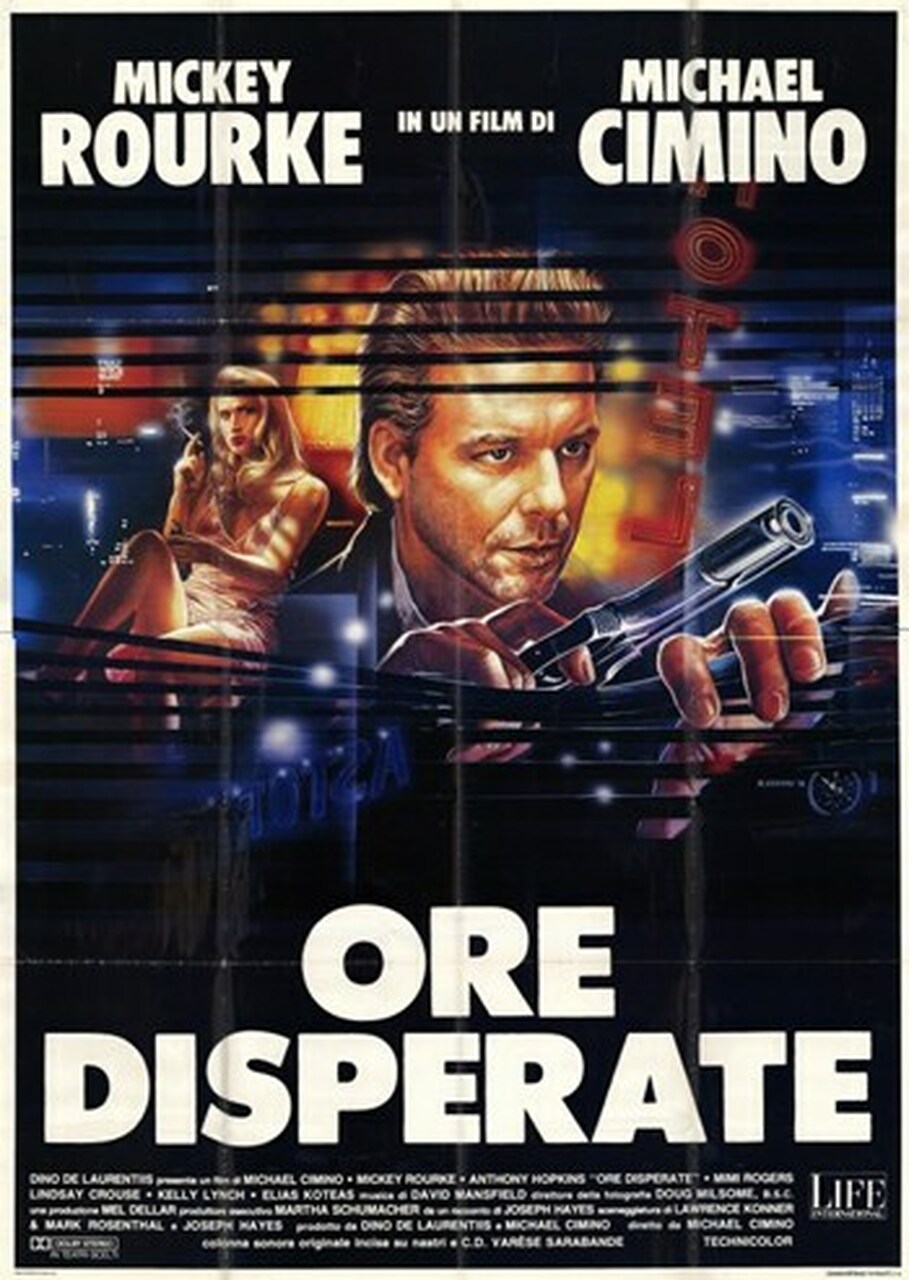

I’d love to make a case that Cimino’s final theatrically released work, Desperate Hours, is an overlooked gem. I have a big soft spot in my heart for the megalomaniacal auteur, but unfortunately I cannot make such a strong case in good conscience. Though not without an intriguing premise, numerous moments of visual splendor, and several memorably bombastic performances, it is ultimately hamstrung by a hilariously incompetent screenplay, a ridiculously inappropriate score, and a frequently stagnant atmosphere.

The primary misstep here is that Cimino and his trio of screenwriters (Joseph Hayes, Lawrence Konner, Mark Rosenthal1) chose to bolster the least meritorious elements of their source material—an old William Wyler/Humphrey Bogart picture from 1955 which was based on a play which was based on a novel which was ostensibly based on true events. Here we have an escaped convict, Michael Bosworth (Mickey Rourke), his brother Wally (Elias Koteas), and the half-witted Albert (David Morse) looking for a temporary hideout while they wait for Michael’s lawyer/lover (Kelly Lynch) to meet up with them. For some reason they choose an occupied house as their hideout and take the family hostage.

Everyone who sees the film will ask the same question: why did they choose an occupied house instead of a seedy motel, or the woods, or the car? Better yet, why didn’t they just make plans to meet Bosworth’s ladyfriend in Mexico instead of waiting for her to head there? In other words, why didn’t they avoid the entirely contrived conflict? The plot of Wyler’s original is equally as preposterous as Cimino’s remake, but the older film is a character piece that hinges on the conflict between the convict and the man of the house which allows us to ignore a gargantuan plot hole and enjoy the drama. Cimino’s work departs from Wyler’s blueprint by placing its emphasis on the details of the silly plot, predominantly concerning itself with the wild contours of Bosworth’s slapdash escape plan, obviously hokey from the film’s opening scenes.

The inane plot would be forgivable—if mismatched with Cimino’s grandiose vision—if the scenes between Bosworth and the father, Tim Cornell (Anthony Hopkins), had a suitable level of ferocity. After all, Cornell is an antihero, an unfaithful husband who is meant to win back his wife’s trust and admiration by thwarting the sociopathic Bosworth and his goons. There is a platform and a need for some serious pyrotechnics here if we’re going to buy that dramatic arc. But these scenes never generate a consistent or compelling tone.

For a large chunk of the film, there are seven people jammed into that suburban house—the three criminals, the father, his estranged wife Nora (Mimi Rogers), and their two children, May (Shawnee Smith) and Zack (Danny Gerard)—each of them operating with differing levels of vigor and seriousness. It’s almost difficult to call any of the performances out as legitimately poor; they’re just at odds with one another. Indeed, almost any of the performances could work if they were unfolding in concert with the others. But they’re not. They’re all over the map and so the viewer has to take them in at a weird arms’ length, neither earnestly committing to the family drama nor enjoying the excessive thrills for their own sake. Perhaps the crowning jewel of this odd concoction is Lindsay Crouse’s turn as the FBI agent heading an overblown operation to track down and capture Bosworth. Boasting a halting southern accent and barking out insults and cheesy one-liners with swagger, she obliterates any slow burning intensity that had been worked up inside the house and prevents the viewer from interpreting Desperate Hours as anything but camp.

And yet, despite these and many additional blunders—including misguided focus on a number of extraneous subplots such as May’s persistent boyfriend (who somehow gets through the police barrier?), Albert’s failed solo escape, and a headbutting contest between Crouse’s character and Dean Norris’ local officer—Cimino’s forceful direction and Rourke’s charismatic excess compensate just enough to make Desperate Hours compulsively watchable. It’s true that Rourke rarely seems in-sync with his fellow actors, but he gives the entire production a lift with his psychotic musings and unhinged decision-making, even if his character is a poorly written caricature. And Cimino, ever the visual talent, showcases his compositional chops anytime he’s able to move the camera away from the melodrama in the Cornell house and out into the mountainous vistas of Utah. A narrative detour to follow the mumbling Albert as he disposes of a body in a gorgeous ravine doesn’t make sense until you realize that it serves as a platform for Cimino to show off with a cinematic spectacle. Police helicopters, snipers in trees, roadblocks—these things only work when you’re thinking in terms of pure, unadulterated style. And it doesn’t really work to open the film with a car chase except to establish a certain visual aesthetic and a feeling of momentum. Even inside the home, though, as he works on a kinetic visual style and artistically commits to the project despite the inherent silliness of the narrative, Cimino provides his film with an undeniable sense of forward motion that greatly aids in smoothing over the glaring holes in the plot.

It can’t be “so bad it’s good” because too much of it is legitimately good to view it that way. Rather, while it’s overall quality may be middling, it’s worth being admired for its positive qualities rather than outright dismissed for its drastic shortcomings. Indeed, concerning visuals, star power, and general narrative flow, Desperate Hours would probably pass the sniff test for a majority of undiscerning viewers. I’d even go so far as to say that it’s better than the majority of similar mid-budget action films released today (at the very least, it’s certainly more interesting). But coming from a former prodigy, or however you want to view Cimino in the aftermath of his supernova, there are certain expectations that are not met. His early success doesn’t make any of his later work inherently bad, but it’s simply impossible to refrain from assessing it in the shadow of his previous efforts.

1. It’s debatable how much input Hayes had here. Considering he had written the novel, the play, and the screenplay of the original film, one would be inclined to argue that he wouldn’t have butchered his own work like this. Considering Rosenthal and Konner have co-written a number of other stinkers, I think we can safely excuse Mr. Hayes.