“A man curses because he doesn’t have the words to say what’s on his mind.”

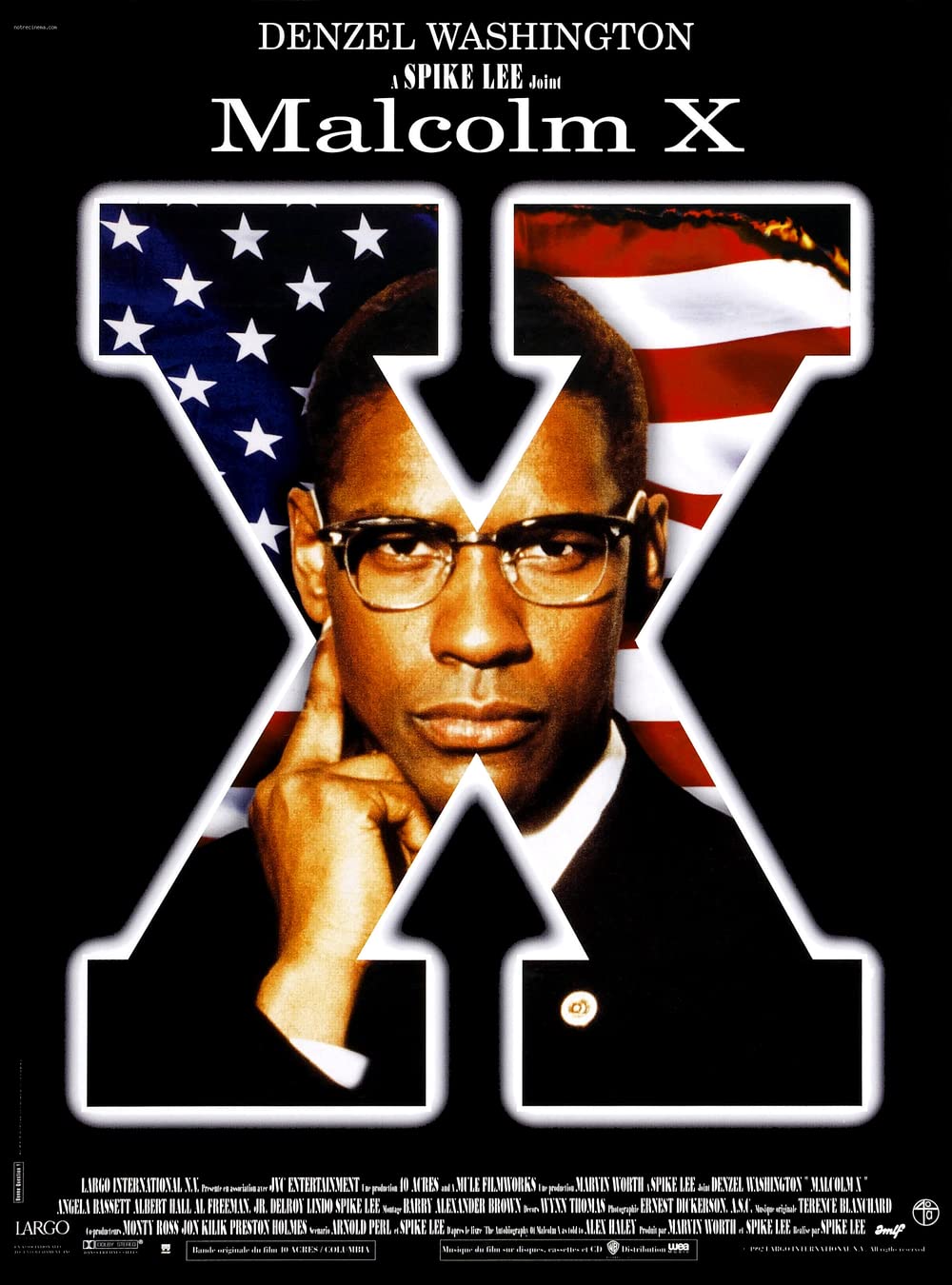

The sheer ambition of Spike Lee’s Malcolm X recommends it to cinephiles, while those merely interested in the cinematized life of the divisive historical figure will find a compelling treatment of the man throughout his myriad personal and spiritual transformations.

Clocking in at just under three and a half hours, Lee’s opus throws out a mesmerizing arrangement of cultures, characters, eras, and agenda-laden diatribes that coalesce into a substantial piece that is neither overcrowded nor reductive (two problems that hamper some of the director’s other work). Though even at such length it might be accused of occasional skimming, it attempts to tell the comprehensive story, beginning with an impoverished upbringing in Michigan and then moving through the young man’s foolhardy days as a depraved racketeer and wannabe gangster in Harlem, his enlightening prison stint, his decade-plus religious formation under the tutelage of Elijah Muhammad (Al Freeman Jr.), his pilgrimage to Mecca and subsequent break from the nation of Islam, and finally his assassination at the Audubon Ballroom at the hands of his former brethren.

Elsewhere Lee’s flashy style tends to scan as bombastic, but here he is in masterful control of himself, transforming his film alongside his subject. Music, editing, voiceover, lighting, camera angles, and even the film stock are carefully arranged to emphasize the character’s state of mind. The horrific episodes remembered from childhood are rendered a nightmarish blur. His salad days in Boston and Harlem are marked by colorful suits, jazz music, and stylish crane shots. His courtship of Betty Shabazz (Angela Bettis) is touching and lighthearted. The pilgrimage is by turns awe-inspiring in its sense of religious community and reverent in its quieter moments of solitary worship. At interesting places it switches to black-and-white, perhaps to clarify that the scene in question involves no creative liberties. In its final segment, as Malcolm X seems to knowingly approach his death, it turns languid and funereal. “It’s been too hard living, but I’m afraid to die, ’cause I don’t know what’s up there beyond the sky” Sam Cooke croons as X glides wraithlike toward the Audubon Ballroom. In the dressing room he murmurs to himself, “It’s time for martyrs now,” as he questions whether he should cancel the conference. The film’s coda, an extended documentary passage consisting of clips and photos of the real Malcolm X set to the eulogy Ossie Davis delivered at his funeral, enhances all that came before it.

If, as the director claims, Malcolm X was the film Spike Lee was born to make, then Malcolm X may very well be the role Denzel Washington was born to play. Essentially tasked with embodying three distinct personas—the jive-talking hustler who’s convicted and sentenced, the zealous street preacher who espouses a half sensical racist ideology, the disillusioned prophet who refashions his religion to conform to his newfound views—Washington proves a match for each. As Red, he inhabits the zoot suit and conk and trades tough guy remarks with his mentor West Indian Archie (Delroy Lindo), who gets him hooked on cocaine and illegal gambling schemes. His slow conversion under the discipleship of imprisoned apostle Baines (Albert Hall), capped with a mystical vision, finds the actor slowly dropping the sloppy diction of Red in favor the rhetorical speech patterns that are later used to address the public. It’s an impressive transformation in demeanor that coincides with an internal one, as the previously apolitical and amoral Malcolm begins to adopt perspectives on various issues relating to race relations and religion. One could knock Washington simply because his popular work as “good guys” undercuts the potential menace lurking behind X’s vicious tirades, but that seems unfair to me.

Like Christianity, Islam comes in various strains and flavors, some of them quite extreme in their beliefs. While the distorted image of Islam suggested by the film’s middle portion is eventually clarified—turns out not all Muslims are black separatists—the same cannot be said about the asinine version of Christianity depicted by Christopher Plummer’s prison chaplain. “God is white, isn’t it obvious?” he says when Malcolm asks about the color of Jesus’ skin (a statement that basically disqualifies a person as a Christian minister). A late encouragement that “Jesus will protect you” does little to rectify the film’s dismissive treatment, even if it does stir up interesting questions about how Christians should respond to inspiring public figures who do not share their faith. No matter, it’s a small unfortunate blunder in an otherwise stellar biopic.

Further criticisms could be aimed at the myth-patterned narrative—largely drawn from The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a text that has taken on a religious aspect over time—or the actions of the man himself. Indeed, it strikes one as absurd that we’re asked to accept Malcom’s initial conversion (complete with a vision of Elijah Muhammad in his jail cell) as a genuine religious experience, only for the film to forego any kind of personal introspection when his faith is undercut by his mentor’s serial philandering. If Elijah Muhammad was a false prophet, what was that apparition? A demon? The question is never asked. Malcolm moves between his phases with utter sincerity, never questioning himself despite the radical shifts in his ideology. From one headstrong passion to another. But of course it is that same uncompromising nature that makes him a compelling figure in the first place. The main contention then, is that one need not accept the sanitized Malcolm X legend as life-changing truth to find his life captivating, and thus, one need not treat Lee’s film as factual to enjoy or draw meaning from its rangy drama.