“With all due respect, your honor, we don’t live in this courtroom, do we?”

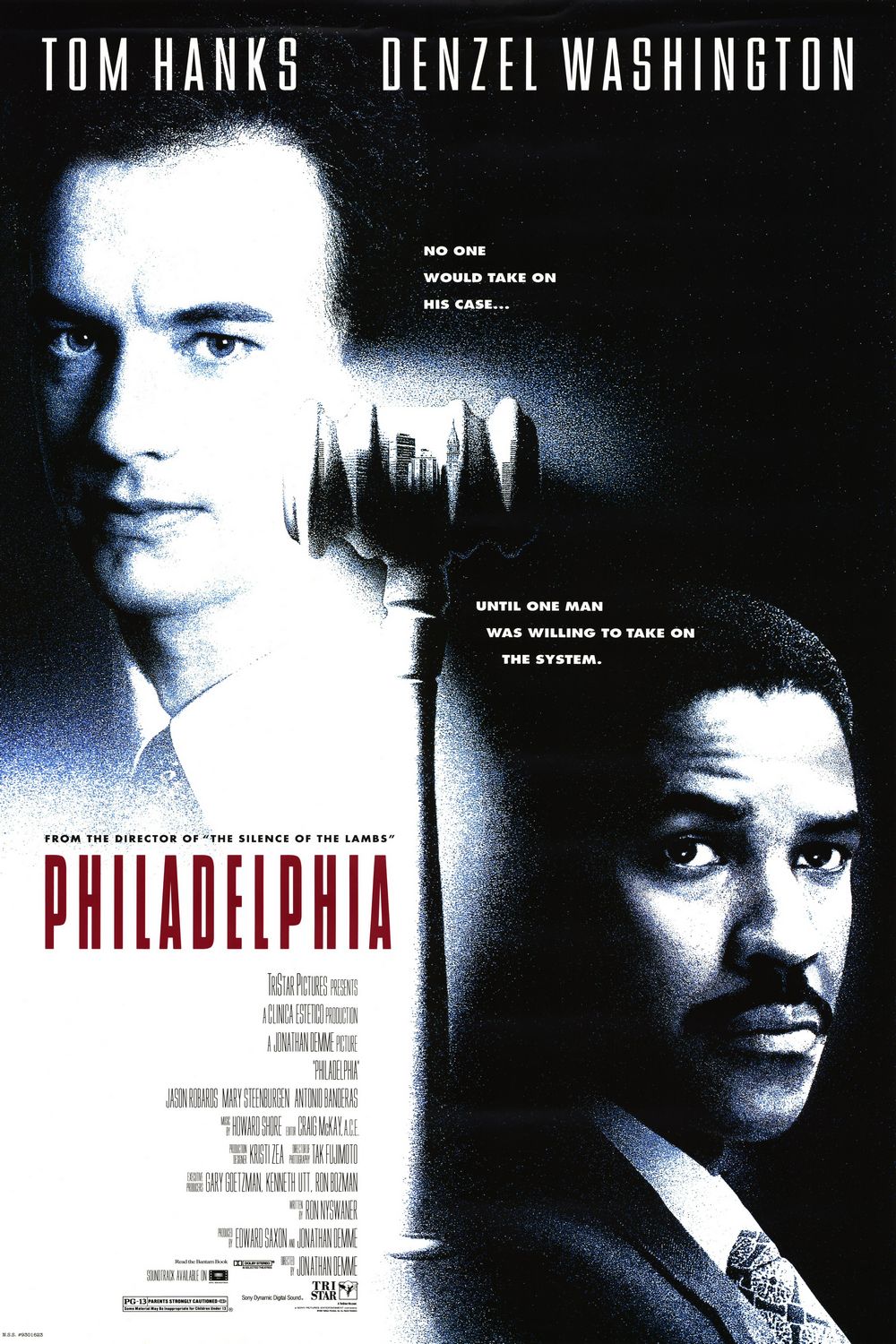

In Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia, Tom Hanks plays Andy Beckett, a promising young lawyer at a prestigious law firm in the City of Brotherly Love. He has a brilliant legal mind, a sharp-witted persuasiveness, and a strong work ethic. Considering these qualities and the future successes they will bring to their firm, the shrewd old partners at Wyant, Wheeler, Hellerman, Tetlow, and Brown decide to make Beckett a senior associate. But Beckett has a secret. Unbeknownst to his colleagues, he’s a practicing homosexual and has been gradually succumbing to the effects of AIDS for several years.

On the same night that he’s promoted and given a potentially lucrative case with a big client, one of the partners spots a lesion on his forehead—a marking that Beckett blames on a racquetball injury but which is actually a symptom of Kaposi’s sarcoma. After a few days at home trying different methods of concealing the spreading lesions, all the while still working diligently on the case, Beckett receives a frantic call asking for the whereabouts of crucial paperwork that has apparently gone missing. It’s found at the last minute, but Beckett’s role in the misplacement of such important documents is grounds for letting him go. Or so the partner’s say. Beckett’s hunch is that the missing documents were a setup; that he was fired immediately upon the realization that he was gay. And so even though his health is in rapid decline, he seeks legal representation for a discrimination case.

Enter Joe Miller (Denzel Washington), a hotshot television lawyer who seeks out prominent cases. He’s acquainted with Beckett—the film opens on the two representing opposing sides in an unrelated case—but initially turns down the case because he, too, is homophobic, not to mention uninformed. After Beckett reveals the reason for his visit, Miller’s mind slips into panic: he shook this man’s hand! Can he risk taking this illness home to his wife and newborn child? Tak Fujimoto’s camera is brilliant here, taking on Miller’s point of view as it worriedly jumps around the room, observing, mentally cataloging everything that has been touched and might need to be chemically cleansed. He makes an emergency visit to his doctor who ensures him that shaking Beckett’s hand is not a cause for worry. A few days later, while Beckett prepares to defend himself by gathering materials at a law library, Miller witnesses the sick man subtly mistreated because of his visible condition, and agrees to represent him; at which point, Philadelphia becomes a more or less conventional courtroom film sprinkled with elements of human drama.

There’s an obvious message here, but Ron Nyswaner’s script is astutely layered and refrains from outright pedagogy. While there are a few instances of frustrating transparency—the legal defense strategy employed by Mary Steenburgen’s defense lawyer is laughably weak in various spots—the narrative is morally sophisticated. Consider that Beckett is not treated as an angelic victim. Far from it. He’s initially portrayed as a neglectful workaholic. When pressed in court, he admits to having sex in a porno theater with a stranger while in a relationship with his partner Miguel (Antonio Banderas), a decision that likely resulted in his contraction of AIDS. And Miller, initially a raging homophobe—make note of the screed he delivers to his wife the evening that Beckett makes his initial request—doesn’t become a gay rights activist, or, worse yet, admit that he himself is a closeted, self-hating homosexual. Instead, he merely comes to view Andrew Beckett as a human being, a fellow image bearer of God who deserves the same treatment as anyone else regardless of his perceived sins. This moment of personal transformation is beautifully encapsulated when the two sit down to review the case after a costume party is thrown to relieve the built-up stress of the courtroom proceedings. Miller tries to focus in on the details of the case, but Beckett gets distracted by the opera music playing in the background, becoming so entranced in the music that he appears to have some kind of out of body experience as he listens to his favorite aria for what may be the last time. He ambles around his flat, IV drip in tow, eyes closed, allowing the music to overtake him.

Likely to go unnoticed amidst the emotive drama and courtroom antics is Demme’s stellar work. Whether it’s his eclectic, but carefully integrated music choices—including Bruce Springsteen’s hit “Streets of Philadelphia”—his piercing use of POV shots, his use of montage (even the opening credits sequence is undeniably wonderful), or his ability to make potentially visually bland scenes come alive with creative decision-making, he’s constantly elevating the material. One of my favorite scenes is basically a throwaway. It’s a single long take that begins with the camera aiming out from the box seats at a Sixers game. The camera swings back around to reveal the associates of the law firm who are enjoying the game, unburdened by the fact that they’ve ruined the remainder of Andy Beckett’s life. Julius “Dr. J” Erving enters the suite, walks past a framed photo of himself hoisting an NBA championship trophy, and charismatically greets the associates. A few seconds later, Miller bursts in, calmly munching popcorn from a bag tucked under his arm, and hands Wheeler (Jason Robards) a court summons. In the middle of doing that, he realizes Dr. J is standing right next to him, introduces himself, and slips him a business card. It’s a small scene and includes only a single element that furthers the narrative, but it is an absolutely stunning piece of filmmaking. The film ends on another brilliant note by employing Neil Young’s “Philadelphia” (a moving song in isolation) in combination with Andy’s family gathering at his wake and then an extended montage of home videos from Tom Hanks’ childhood.1

Unfortunately, Philadelphia seems to be seen as a film only rarely. Instead, depending on one’s political stance, it’s positively viewed for its portrayal of a previously shunned demographic (or negatively viewed for making some overly safe narrative decisions, or casting a charming straight man as the lead, etc.) or judged as a piece of failed propaganda. Might I suggest that regardless of its perceived value as a political tool, it is a well-made film deserving of your time.

1. Both “Streets of Philadelphia” and “Philadelphia” were written for the film.