“I have to believe in a world outside my own mind.”

Memento is the early career mindbender that put Christopher Nolan on the map. It features a flashback-heavy, Mobius strip of a narrative that is conveyed to the audience in reverse chronological order, building itself into a satisfying hypnotic puzzle.

The little idea that set Christopher and Jonathan Nolan’s gears cranking and led to Memento was a character with an inability to form short-term memories. Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) suffered an accident and, despite remembering many things about his personal history, cannot keep any new information in his mind for more than a few moments. He begins conversations rapidly so that they will conclude while he still retains the beginnings of them. His body is tattooed with reminders. Among these reminders are details about the attack which left him mentally damaged and his wife dead. Every few minutes Leonard must reassess his situation anew as he seeks revenge for her rape and murder.

At many points in the film, Leonard is either talking to himself, or into a telephone—both of which serve as a kind of narration. Early on, he explains that he is able to condition himself through repetition, but his momentary experiences fade from his mind very quickly. So while he is capable of forming new memories (avoiding the potentially devastating plot hole of explaining how he knows of his condition), he must rely on his map, tattoos, and a Polaroid camera to guide his actions. The film’s opening scene clues us in to the reversal of the narrative’s chronology: Leonard gently shakes a developed Polaroid photograph, which gradually un-develops and becomes black. It is sucked out of his fingers and back into the camera, which flashes.

There are two separate stories unfolding simultaneously: the one already described, in which Leonard’s story is told in reverse order, its scenes overlapping briefly to solidify the structure; the other a series of black-and-white scenes shown in forward chronological order, alternating with the reversed story. In the black-and-white scenes, Leonard is on the phone, describing his career as an insurance inspector. He once had a case where the symptoms the claimant exhibited were similar to his own, except Sammy Jankis (Stephen Tobolowsky) was entirely incapable of forming new memories. Each time Leonard saw Sammy, he thought for a brief moment that there was a look of recognition in Sammy’s eyes. Extensive testing indicated that Sammy should have been physically capable of forming new memories, and so the insurance claim was denied. A tattoo on Leonard’s hand reads, “Remember Sammy Jankis.”

The reversed story is fairly straightforward. It’s innovation and appeal are in its backward sequencing, as we—like Leonard—experience these scenes without knowing what happened in the preceding moments. Leonard is constantly pulling his stack of Polaroids from his pocket to verify who he knows. In the opening scene, Leonard looks at a photo of Teddy (Joe Pantoliano), with a note scrawled on the back, “He is the one. Kill him.” And Teddy does initially appear antagonistic. Having recently portrayed a turncoat in The Matrix, the filmmakers were concerned that Joe Pantoliano would be too recognizable as a villain, but he handles the role with nuance, as Teddy’s character shifts from nefarious to benevolent to carelessly manipulative. Another Matrix alum, Carrie-Anne Moss, fills out the main cast with a solid turn as an opportunistic bartender. She tests Leonard’s memory by spitting in his drink, and uses him to take care of her own problems, though her manipulation is balanced as she dutifully reciprocates Leonard’s help by identifying the owner of the license plate number that is tattooed on Leonard’s thigh.

The concept of confabulation—the production of distorted or fabricated memories—is central here. When Leonard’s method of fact-gathering is questioned, suggesting the superior reliability of direct memories, he fires back: “Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted. They’re just an interpretation, they’re not a record, and they’re irrelevant if you have the facts.” But, despite his methodical note-taking, mapping, tattooing, and photographing, a narrator with a short-term memory of only a few minutes is necessarily an unreliable one.

In the film’s later scenes, Leonard’s robust system starts to unravel. An interesting phenomenon happens, as we have been continuously subjected to his photograph of Teddy, which tells us not to believe his lies. As Leonard’s previously clear version of events becomes murkier, we are still prone to believe his note about Teddy, even as Teddy’s intentions becomes less suspect. Indeed, he might be the only character who can provide a correct version of the events as they occurred. But we don’t trust him—because of the note, and because we know that Leonard eventually gets his revenge by killing him in the “final” scene.

The suspense that is generated by a film which reveals its conclusion in the first scene is a real testament to Nolan’s creativity. The short story on which the film is based, Memento Mori (written by brother Jonathan), is told in chronological order, and though the plots are similar, the film is much more of a puzzle.

The loss of memory is occasionally used as a welcome source of humor in a story otherwise sincere in tone. At one point, Leonard begins running toward his pursuer as he forgets which of them is cat and which is mouse. At another, he kicks in the wrong motel door, knocking an innocent man unconscious. The motel clerk bluntly tells Leonard that he has rented him a second room to make an extra buck, and that he doesn’t mind telling him because he will forget that too. One of my favorite scenes in the film ends with Leonard suggesting that the gun he found in his drawer must not be his. “I don’t think they’d let someone like me have a gun,” he says.

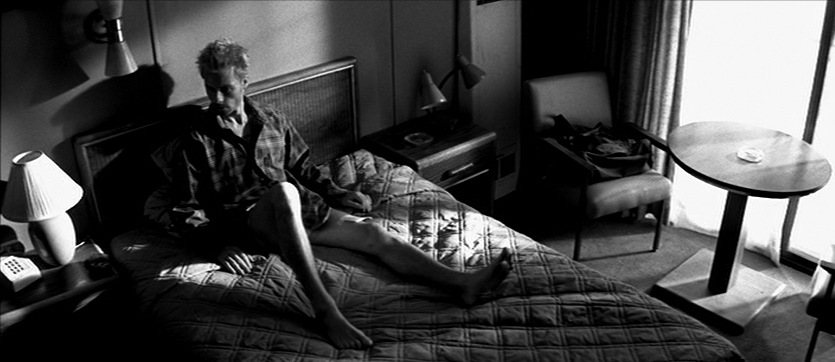

Though Memento is largely a thinking man’s film, interjected into the brainy plot are subtle moments of emotional tenderness. While the film will no doubt fall flat if you aren’t up to the task of unraveling its intricate plot, these heartfelt moments give the film an emotional resonance that grounds its calculated storyline. “How am I supposed to heal if I can’t feel time?” Leonard asks himself, lying in bed with a woman he cannot remember. The extraneous testing that Sammy Jankis’s wife (Harriet Sansom Harris) does to convince herself that the old Sammy is gone is extremely poignant, as is the scene in which she pleads with Leonard (still a fully functioning claims investigator) to offer her a glimmer of hope. There is no doubt that Memento is a fine thriller, but it prompts deeper questions that will linger: did what we remember really happen? Are the experiences logged in our archival memory embellished? How can we know that something is true? It isn’t merely cerebral pseudo-noir. It prompts us to contemplate what it means to be human.

Sources:

Mottram, James. The Making of Memento. 2002.

Intelligent post, much gratitude for this content