“A couple more years and you’ll be a human steamroller, covered with spikes and fueled by bile.”

When Sam Rockwell was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role as the violent, racist, alcoholic Officer Dixon in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, many vitriolic critics cried foul—how morally confused must the voters be to award an actor for portraying such a despicable character? And how dare writer-director Martin McDonagh give him a chance at redemption? Why was he written as a nuanced character instead of a caricature? It seemed so silly to me to see McDonagh and Rockwell dragged through the muck for simply suggesting that a bad person could be redeemed. But it’s especially annoying because all of those aggrieved voices know that conflicted characters make for compelling storytelling—after all, they were engaged enough with the movie to actively hate a supporting character. It’s simply that in our current era, racism is seen as an incurable disease. The only solution is ostracization or maybe death by firing squad. Extending an olive branch to a racist is like touching a leper—do it and you too are now unclean.

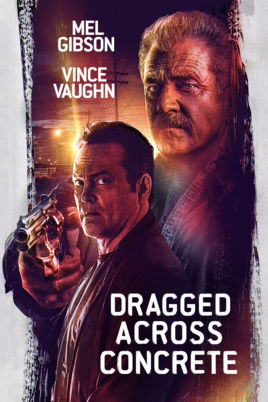

Which brings us to S. Craig Zahler’s Dragged Across Concrete, a languid crime film about two racist cops. Though punctuated by grisly violence, the bulk of the film is long-winded conversation, giving us plenty of opportunity to assess our characters. I can confirm that they’re racist, often blatantly so. Played by controversial Hollywood actors Mel Gibson and Vince Vaughn, our suspended detectives are unapologetic and outspoken, spitting their venom with abandon. When Brett Ridgeman (Gibson) and Anthony Lurasetti (Vaughn) are caught on video treating a Mexican drug lord a bit too harshly, their police chief (Don Johnson) asks them to turn in their badges for six weeks without pay. “I’m not racist,” Lurasetti protests. “Every Martin Luther King Day, I order a cup of dark roast.” Their predicament brings out the worst in them, leading to hateful diatribes and impulsive decisions, and they soon find themselves trying to hi-jack a robbery to make financial ends meet.

But Zohler’s film is larger than these two characters. He doesn’t give as much screen time to anyone else, but his narrative is bookended by scenes concerning recent parolee Henry Johns (Tory Kittles), with other small arcs about a bank employee (Jennifer Carpenter) and a small-time criminal named Biscuit (Michael Jai White), not to mention the masked gangsters that feature in the finale. Each of these characters, even the corrupt cops, have been dealt terrible hands in life. Henry’s young brother is in a wheelchair and his impoverished mother has been working as a prostitute; Ridgeman’s wife suffers from multiple sclerosis, etc. They’re all stuck in some bleak rut or another.

Like cell phones and just as annoying, politics are everywhere. Being branded a racist in today’s public forum is like being accused of communism in the ‘50s whether it’s a possibly offensive remark made in a private call or the indelicate treatment of a minority who sells drugs to children. The entertainment industry, formerly known as the news, needs villains.

In addition to the instances of overt racism, Zohler’s screenplay includes some potshots at other prominent hot-button issues. At times it feels like maybe he’s just thumbing his nose at a Hollywood machine that is no longer willing to make politically unpopular art (if much of what they produce could be called art at all); like he’s being provocative simply for his own amusement. Whatever his aims, his insistence on giving a platform to such politically incorrect worldviews has led to accusations of sympathy with these viewpoints—why else would he be drawn to the material?—and so virtually every piece of criticism reads like a personal attack against the director, rather than a critique of the film itself.

Many of my favorite movie critics could not help but read metaphors into Dragged Across Concrete at every chance. A new mother, struggling to part with her newborn son, is killed on her first day back to work—that means Zahler thinks women belong in the home! Misogynist! Ridgeman is worried about his daughter being raped in a predominantly black neighborhood where she’s been physically assaulted a half dozen times. Racist! Ridgeman asks his partner if the song playing on the radio is sung by a man or a woman—transphobe! Annoyed at a smartphone? Luddite! All of this is stupid and narrow-minded. Zahler’s film, while featuring politically edgy characters, is not endorsing any ideology over another. It’s a movie about crime. The criminals are not angels. Get over it. And for those who think it’s a “racist, right-wing fantasy,” well, spoiler alert, those usually don’t end with the white guys getting killed.

Part of the issue is Zahler’s distinctive slow-burn style. An author as well as a filmmaker, his approach to narrative is literary, leisurely moseying through dialogue-rich scenes, layering the story and building character like a novel, often reminding me of the work of George V. Higgins (and so also Andrew Dominik’s Killing Them Softly). His two central characters engage in banter and scenery chewing, endearing themselves to us with their personality tics like Lurasetti’s frequent use of the word “anchovies” and Ridgeman’s penchant for estimating a percent chance of each possible outcome. A large portion of the nearly 3-hour film is just these two dudes shooting the breeze, staking out their suspects, sharing food, talking about their personal lives. Zahler’s dialogue shines in these quiet moments that would be passed over in more energetic films.

And when Zahler gets violent—which he does repeatedly—boy does he get violent. In many respects, his multi-arced storyline, dense, witty dialogue and violent outbursts could be compared to the work of Tarantino—a clichéd comparison, of course, but one that fits here. The difference between them is that Zahler’s style, while distinctive, is not flashy like Tarantino’s. Even in his goriest moments, Tarantino’s is having fun with homage, music, and theatrics. Zahler does his violence stone cold, with long takes, no music, and horrifyingly visceral effects.

Dragged Across Concrete has been unfairly derided, and it’s director wrongly criticized, simply because its characters’ politics are outdated. But that’s an intentional part of the world Zahler creates, swirling with conflicting ideologies and ideas of right and wrong. Civilians killed without remorse, crooks with hearts of gold, corrupt cops trying to turn a buck to take care of an ailing family—it’s simply an engaging story full of broken characters. There’s no message hidden in here, as much as people want to see one. For what it’s worth, Zahler seemed to anticipate such a divisive response and has taken it on the chin. At least people are watching his movies.