“There’s all kinds of ways to get killed in this city, if you’re looking for it.”

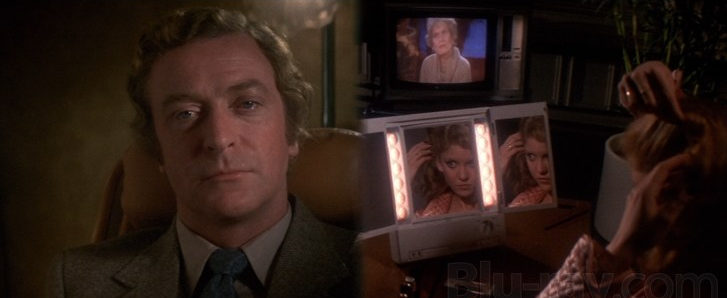

Much like Dr. Elliott (Michael Caine) hides his wicked debauchery beneath an air of sophisticated professionalism, so Dressed to Kill uses the trappings of a classical thriller to disguise its giallo tendencies. Well, disguise isn’t exactly the right word. From the first frame onward, De Palma is pushing all the prurient buttons he knows how to, even as he shows off his technical acumen and encyclopedic knowledge of Hitchcock.

It opens with some gratuitous full frontal nudity, as Kate (Angie Dickinson) touches herself in the shower, turned on by her husband’s (Fred Weber) offhand glance through the steamy haze in the bathroom as he shaves. Cut to a sudsy boob occupying the entirety of the frame while Kate is fondled by an imagined lover who holds her from behind. Then we’re onto a closeup of her pubic hair. (Neither the breast nor the bush belong to the actress; her stand-in is 1977 Penthouse Pet of the Year, Victoria Lynn Johnson.) There are many people that I know who would have turned the film off then and there and chalked it up as irredeemable hog slop—which I think is precisely the director’s aim. De Palma wants the viewer to know up front that this is a deeply sleazy picture that intends to luxuriate in depravity. He took his nose-thumbing to such an extreme that Dressed to Kill originally received an X rating from the MPAA; not just for this masturbation dream sequence, but also the violent slitting of a throat and sexually explicit dialogue.

Anyway, the reason that Kate feels the need to pleasure herself and dream about other men caressing her is that her husband is lousy in bed. In fact, from what we can see, he’s pretty lousy across the board. Sexually frustrated, Kate tries and fails to seduce her psychiatrist, the aforementioned Dr. Elliott, then visits the Metropolitan Museum of Art where she wordlessly picks up a complete stranger in a tense lover’s game that crisscrosses the museum’s labyrinthine hallways, gathers steam during a taxi ride, and ends in the shadowy depths of the man’s apartment. After the entanglement, while the man lies asleep, Kate peruses a desk drawer with the intention of leaving a silly note only to discover a letter from the Dept. of Health notifying the addressee that he’s contracted a venereal disease. Flustered and thus distracted, Kate briskly makes her way to the elevator, trying to distance herself from the situation. Except wait, did she really leave her wedding ring on the skeeve’s nightstand? It’s while making her second trip that she’s accosted in the elevator by a blonde psychopath in sunglasses who slices her up with a shaving razor.

It’s at this point that the narrative is handed over to Miss Liz Blake (Nancy Allen), a prostitute who witnessed the murder—she becomes the prime suspect and the real killer’s next target—and Peter (Keith Gordon), Kate’s nerdy teenage son. The unlikely pair team up to track down Kate’s killer. This involves staking out Dr. Elliott’s office and working around a pushy detective (Dennis Franz). Through Keith’s practical ingenuity with esoteric homemade gadgets, Liz’s gumption, and sheer dumb luck, they manage to catch the serial killer, who is, of course, Dr. Elliott’s transvestite alter ego, Bobbi.

Arguments over the sordid content of the film have raged over the decades. Is the twist a suggestion that trans people are, as a general rule of thumb, bloodthirsty freaks suffering from multiple personality disorder? What is the director trying to say when Liz is chased by a group of black men on the subway? How about when he immediately punishes his adulterous main character with not just a sexually-transmitted disease and racking waves of guilt, but also, you know, death by razor blade? I view all of this as more provocation, not anything with deeper meaning. It’s all part of the game for De Palma. Just as he uses his film as a playground for trying out various methods of staging set pieces; just as he employs well worn tropes and character traits; so he intentionally agitates with unseemly inclusions. In other words, it’s bait.

Despite its trashiness, Dressed to Kill is not very hot blooded at all. In fact, it’s quite cold and mechanical, especially during the set pieces. This is because De Palma’s primary passion here is not for the material itself, but for the act of filmmaking and manipulating the audience in the mold of Hitchcock’s Psycho. Borrowing numerous bits of plot and utilizing a similar narrative structure, De Palma’s film can be seen as a lurid remix, pushing the boundaries of acceptability of his own era but remaining faithful to the form of his idol’s masterwork. As fun as it is to trace the parallels (more so than when doing the same exercise with Gus Van Sant’s Psycho), the precision of De Palma’s mimicry sucks a lot of the liveliness out of the proceedings. Plot devices are ruthlessly contrived, characters remain one-dimensional and functional, emotional engagement is next to nil. That’s not to say that it doesn’t work. Its manipulations work incredibly well. However, the resulting enjoyment occurs from a slight distance. The viewer finds pleasure in being played, like watching a magician pull off a neat trick; wowed but not moved by the deft sleight of hand.

Though Dressed to Kill quotes Psycho extensively, it also borrows quite liberally from the likes of Bava and Argento. An operatic score (Pino Donaggio), ostentatious camerawork, selective but gratuitous and vivid blood-letting, uncertain memories, dream states—all of these elements are standard-issue ingredients in the best giallo thrillers. Further, though, it also quotes itself, running through its basic plot in a post-climax scene at a restaurant that lets other patrons stand in for the audience, repulsed as they are by the explicit details of Dr. Elliott’s story.

Prudes and ax-grinders can argue about depravity and subtext all they want; but I doubt either group is capable of making a case that Dressed to Kill isn’t consummately watchable.