“I don’t want any kind of love anymore. It doesn’t pay off.”

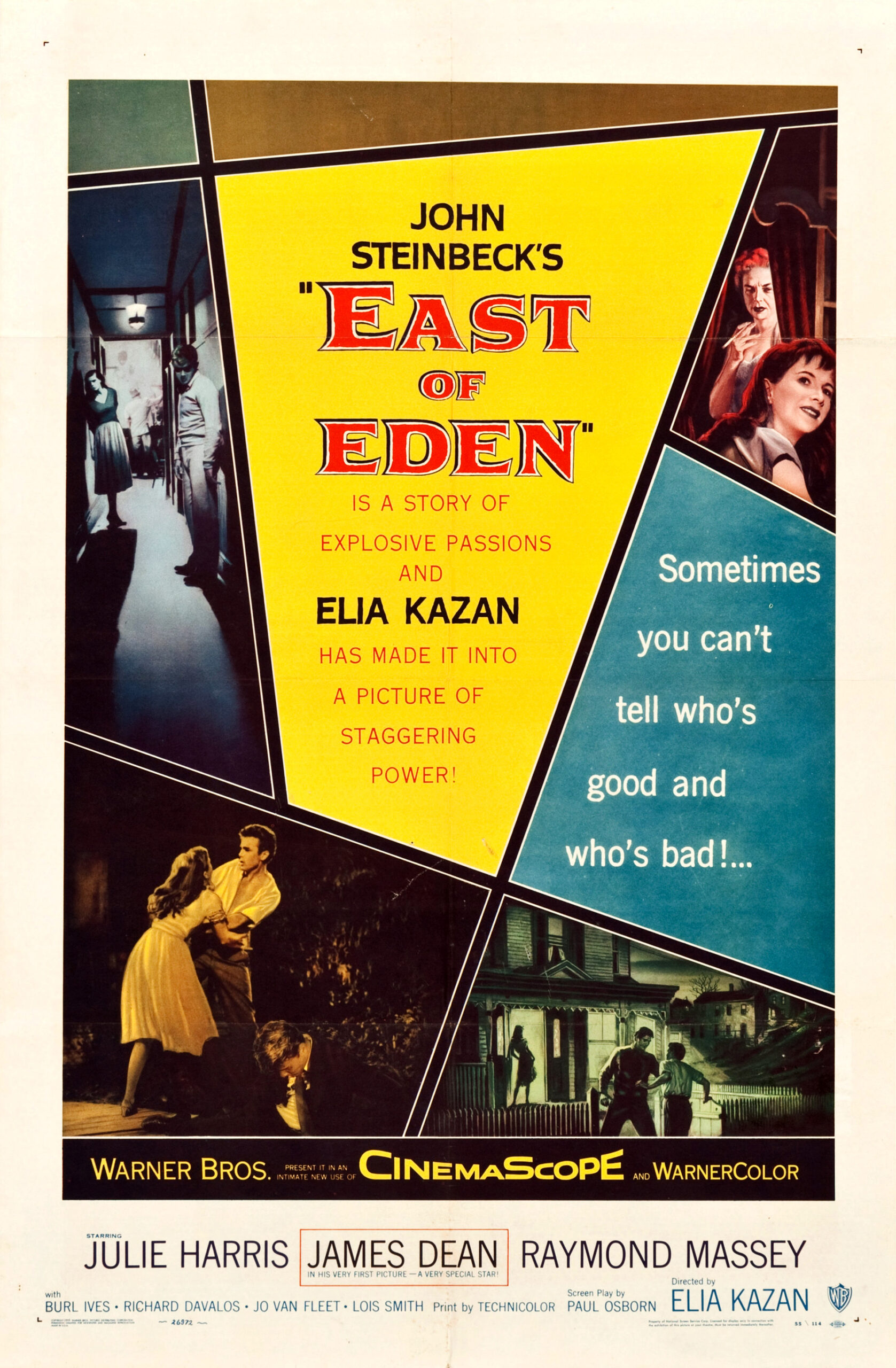

James Dean was a shooting star who rapidly defined the mid-50s rebellious, disillusioned, American teenager in three films before dying in a car crash at the age of twenty-four. The first of these, and the only one that made it to the screen during the actor’s lifetime, was Elia Kazan’s East of Eden, an emotionally stirring adaptation of a portion of John Steinbeck’s perennial classic novel. It concerns the lives of two brothers, Cal (Dean) and Aron (Richard Davalos), each with their own unique demons, who take on the aspects of the biblical Cain and Abel as they vie for the approval of their enterprising, principled father (Raymond Massey) and the attentions of a shared sweetheart (Julie Harris). Complicating matters is Cal’s recent discovery of his absentee mother (Jo Van Fleet), whom the brothers were led to believe had died years ago but now operates a nearby bordello. Set in rural California and backdropped by World War I, the film is beautifully shot (Ted McCord) and scored (Leonard Rosenman), and crafted with a bold compositional eye (note the incredible tension in the shot where Cal is swinging back and forth while talking to his father on the porch and the way the camera mimics his movement) that breaks from classical styles when it wants to emphasize Dean’s jittery energy. Kazan strikes a subtle balance between engrossing period drama, contemporary Beatnik attitudes, popular existentialist philosophies, broad allegorical insight, and the use of symbols. But the real selling point here is without a doubt the brilliant performances not only from James Dean in his star-making role as the precocious, irreverent, restless, skulking, guilt-ridden Cal (he was immediately cast as the angsty Jim Stark in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause) but also each of his previously mentioned co-stars and a strong supporting cast.