“Enjoy the absurdity of our world. It’s a lot less painful, believe me. Our world is a lot less painful than the real world.”

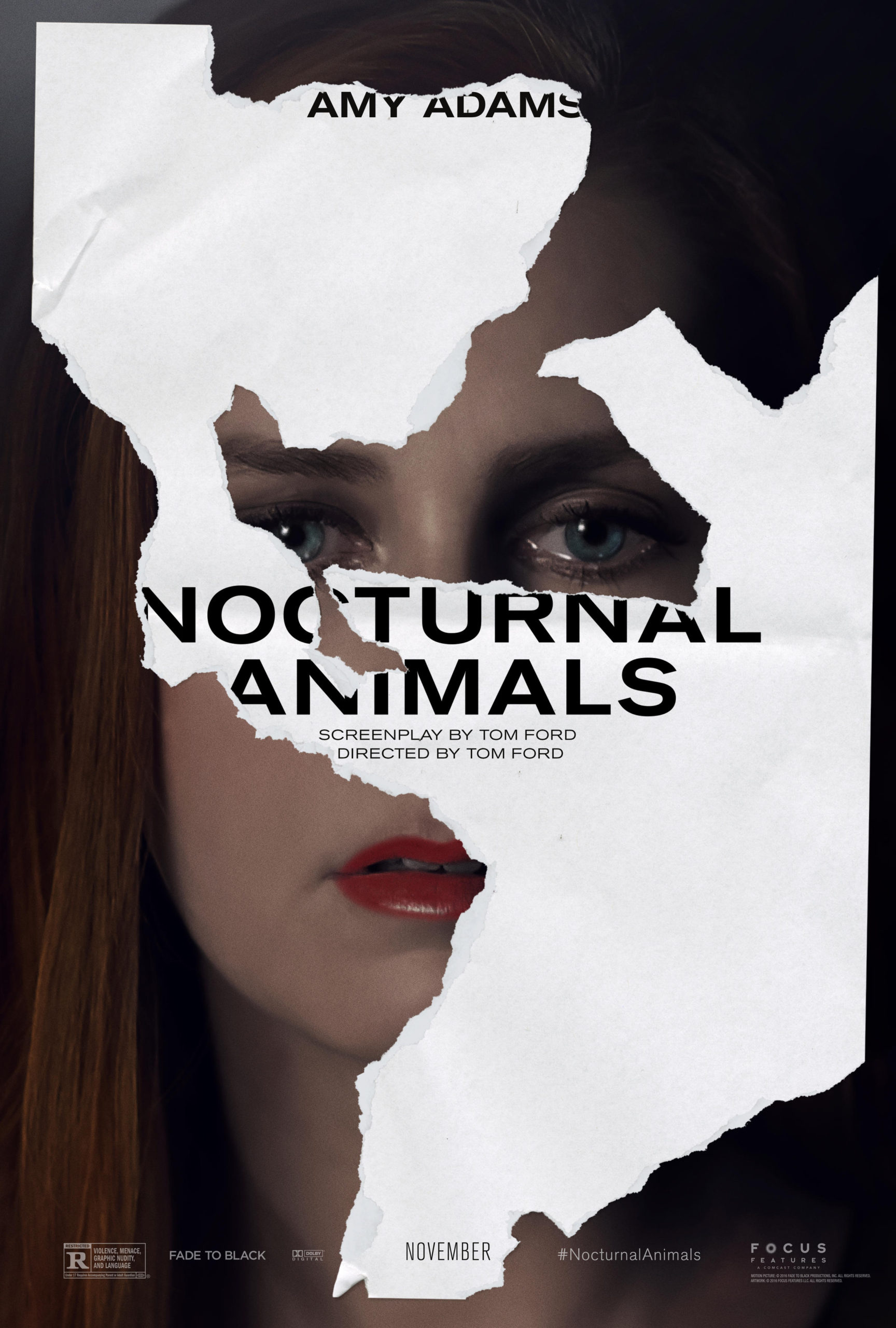

Fashion designer Tom Ford’s second film, Nocturnal Animals, is about a lot of things: finding catharsis in the realm of fiction; the inseparability of the artist from their art; guilt, betrayal, revenge; how the past shapes the present; the process by which we mentally recreate scenes from the text of a book. It is predictably loaded with style, and contains a pulse-raising movie-within-a-movie; yet too often feels like a careful construction of cinematic elements rather than an organic creation, and ultimately has very little to say about its subject matter.

The film begins with a needlessly shocking art exhibit: nude women projected on giant screens, dancing with pompoms and sparklers. Such a scene would be sure to raise eyebrows as described, but these women are also morbidly obese to the point of looking inhuman, and the footage is in slow motion. As Susan (Amy Adams)—owner and host of the “progressive” L.A. art gallery—says later, “It is junk. Total junk.” Shamelessly provocative junk that has minimal connection to the rest of the film.

So, after you pause the film, take a shower, and bleach your eyes, Susan receives a manuscript from her ex-husband Edward (Jake Gyllenhaal) whom she has not spoken to in nearly twenty years, accompanied by a note thanking her for the inspiration. She and her current husband—a jaded businessman played by Armie Hammer—fumble through a stunted conversation. Why had he not come to the premiere of the exhibit of nude women? Why had he not come to bed last night? Would he like to go to the beach this weekend? No, he must fly to New York on “business” (he is cheating on her). Susan, alone, settles in to start reading the manuscript, which is titled “Nocturnal Animals” and is dedicated to her.

In the story world, we follow Tony Hastings (also Jake Gyllenhaal) as he drives across West Texas with his wife, Laura (Isla Fisher) and their malcontent teenage daughter, India (Ellie Bamber). In the middle of the night, the family is run off the road by a gang of stereotypical brutish punks, led by Ray (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). The sequence is long and delightfully uncomfortable, and while there is minimal physical violence, it is terror-inducing and will get your heart pounding. The scene ends as Susan slams the manuscript shut.

That, to me, is the high point of the film. The scene is visceral and feels more real than the world which Susan inhabits. When she closes the manuscript, we realize that we have been manipulated into believing that the story in the book was real; but it’s not, it’s only a story. That scene was only what Susan imagined while she was reading. But then you realize that’s what every movie, every book, every work of art is meant to do. What you’re watching is just film, what you’re reading is just text, and what you’re viewing is just paint on canvas—in other words, what you understand a work of art to be is really just your interpretation of it.

For the rest of its duration, the film jumps around amongst the story in the manuscript, Susan’s life in the present, and the episodes in Susan’s past that inspired the scenes her ex-husband wrote into the book. Where the film does well is in its deft sequencing; it reveals just enough of one plotline to push the story forward, then cuts to another, and reveals a little bit more from a different angle; rinse, repeat.

In other areas, though, the film is a bit clumsier. Once we understand that the narrative of the story is meant to mirror the emotional pain that Susan caused Edward, we are presented with several scenes detailing their past together so we can begin making connections. In one of them, Susan launches into a ham-fisted diatribe against her parents, who she describes as “religious, conservative, sexist, racist, Republican, materialistic, narcissistic, racist” (yes, racist is in there twice). In an earlier scene, we are treated to a discussion on the merits of a lady having a gay husband. Neither conversation has anything to do with the plot, and they serve rather as amateur liberal apologetics that detract from the film.

It offers shallow critiques of the objectification of women (Susan’s labeling of her parents as misogynists, the flabby dancers, etc.) yet it is very careless in checking itself for the same issues. For instance, how are we to interpret the beautifully arranged corpses that Tony and Bobby (Michael Shannon) find on the bright red sofa? It is almost as if, by placing the obscene imagery in the imaginary world of the manuscript—where it is a stand-in for the emotional violence that inspired it—the film thinks it is absolved of the wrongs it points out in others. (“First, remove the plank from your own eye,” etc.) To be clear, I don’t have an issue with the shot of the bodies on the couch itself—Ford knows how to compose a shot—but with the inconsistency of the film’s politics and its content. And if the film was trying to present this image ironically, it failed to do so.

Susan and her mother (Laura Linney) argue over whether Edward is suitable for marriage. Her mother insists that Susan will eventually desire the things that a marriage to someone of equal social stature would give her, that Edward cannot. Based on what we know about Susan already, her mother was clearly correct in her assessment of her daughter. In the same breath that she criticizes her parents for representing a slew of stereotypes, she makes it clear that she wishes they would just accept her for who she is, just as she wants them to accept her openly homosexual brother. Yet now, instead of accepting herself as she is, she falls in love with Edward all over again while reading his manuscript, and the tone of the film suggests that her course of action is the correct one. It makes no difference to me which path she chooses, but the message of the film is as confused as its protagonist.

After the intensity of the opening scene of the manuscript, the written story becomes the most engaging of the three. Tony is aided in his quest for justice by classic Texas detective Bobby Andes, portrayed by an incredible Michael Shannon. He is perfect in the role, exhibiting a subtle humor that makes the character feel lived in and experienced. In fact, the main cast all deliver excellent performances. Gyllenhaal is dependable and especially excels in the scenes where his character is mentally spent, unable to string coherent sentences together. My favorite line of his is when Andes tells him they have a promising lead. He struggles to respond, forcing the question out as he contorts his face: “Promising?” (This is notably Gyllenhaal’s second dual-role after Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy.) Aaron Taylor-Johnson is believable as the perverted hillbilly Ray Marcus, and Amy Adams is emotive as Susan—though she is limited by a patchy script.

I wish the film sat better with me, because there are definitely many pieces here that work well. Ultimately, where the film falls short is that while the manuscript is engaging, it is, at best, an average story. Sure, it is gripping, because it is acted well, but it isn’t great. If one of the thrusts of the movie is that great art can be a byproduct of great pain, well, then I understand the source of Edward’s great pain, but it merely produced a script for an intense short film, not the profound allegory we are meant to understand it as. Susan has a strong reaction to it because she knows it is about her; we have a strong reaction because we are not reading the book, we are watching the movie version which is well made. The metaphorical links between the two—societal and familial pressures represented by the gang members, abortion by murder, and a vengeful conscience by Bobby Andes—make sense, but are just… there. The physical items that connect the two—a green Pontiac, a red couch (both pointed out by Ford in the supplemental material as seemingly profound links between the stories)—are very superficial. They are nice to have but do not truly add any potency to the novel.

The melodramatic story that frames the thriller never solidifies into a story of substance, and so the inspiration for the novel feels like a stretch. Maybe the complex process of turning inspiration into a finished work of art is simply too abstract to capture in such a calculated way. Or, it may be the case that too much of this film was lost on the cutting room floor as it was whittled down to feature-length, because I think the basic idea could have worked very well. Had the script been more focused on the act of creation, and spent less time on its throwaway social critiques, it could have been much better. In any case, the film feels bloated yet incomplete; exquisite at times but ultimately unfulfilling (and possibly unwholesome).

If you have a strong stomach, it is worth watching. Many critics seemed to think it was an instant classic, but I am obviously less certain. That being said, if you ignore the film’s unclear meta-commentaries on art culture, the objectification of women, the relationship between an artist and their work, etc. and just watch the film for entertainment, it is a fine thriller. Just don’t try to read too much into it.