“You really have to raise hell for the old pig to notice.”

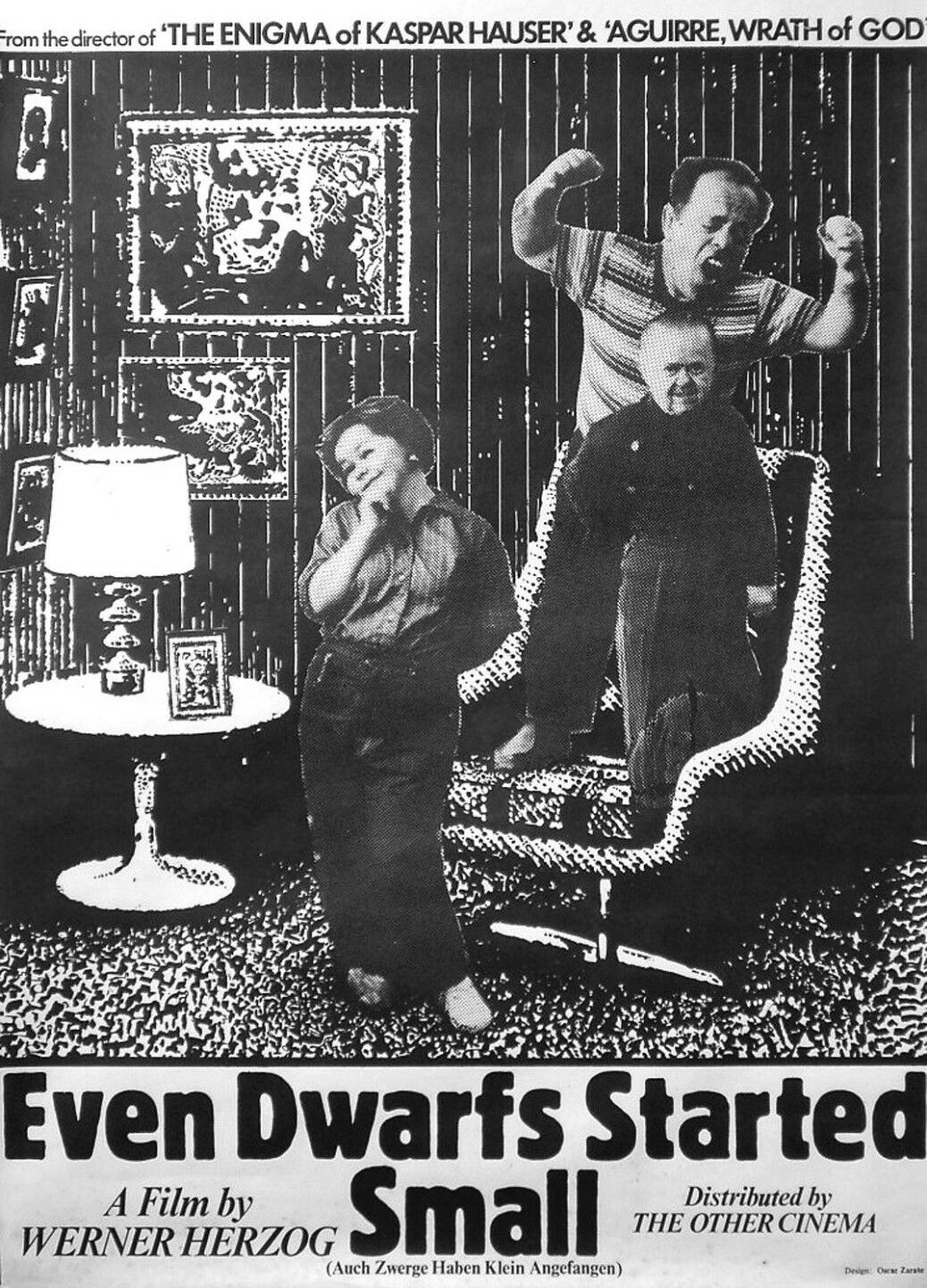

One of the few dwarfsploitation films in existence, Werner Herzog’s second feature is a black-and-white black comedy that is equal parts intriguing and unsettling, though it may prove a mere curio for those interested in perusing the entirety of the director’s large body of work. Shot in the wake of the torturous Saharan production of Fata Morgana (including arrests and the contraction of bilharzia), Herzog came to the shoot for Even Dwarfs Started Small with fire in his belly, aiming to put to celluloid a gloomy vision to rival the paintings of Francisco Goya and Hieronymus Bosch.

The utterly macabre film documents a dwarf uprising at a penal colony isolated on a desolate volcanic island, a startling little pocket apocalypse that seems incongruent with reality. Reveling in nightmarish imagery and themes of chaos and destruction, it forgoes a strong narrative in favor of a series of non sequitur dwarf shenanigans. It may bear the markings of satire, social critique, and allegory, but it never rises above the level of exploitation—although the director would say that his film is neither political nor exploitative. Maybe he was simply amused by visions of munchkins run amok and a live monkey hanging from a crucifix.

Here are a few things you’ll see as the all-dwarf cast locks their overseer (also a dwarf) into an administrative building and wreaks havoc on the facility: a chicken cannibalizing another chicken; a captive dwarf bound to an office chair who cannot stop himself from laughing giddily; a driverless car circling a courtyard while dwarves dance around it, pretend it is a charging bull, and ride atop it; two blind, begoggled dwarves perpetually swinging sticks in self-defense; two dwarves forced into a bedroom to copulate, the male unable to “get up” onto the bed (they end up looking at pornographic magazines together instead); a food fight; a cockfight; the torture of pigs and a monkey hung on a cross; a dwarf picking skin from her leg and eating it, then looking ashamedly at her companion, as if she had been caught instinctively doing something that she usually only does in private, only for the other dwarf to ask if they too might try of a bite of leg skin; and a dwarf laughing hysterically while a kneeling camel poops.

If there is a parable buried within Herzog’s esoteric collage, it’s that we all want freedom but would be quite useless and even horrifyingly destructive if it were granted to us. The dwarves successfully overthrow the dastardly warden, but to what end? To tear down their master’s favorite tree, light potted plants on fire, pick on one another like children, wreck cars, and ritualistically torture animals. It’s not even sophisticated evil; just schoolyard nastiness. And when the inmates venture outside of the places they are familiar with, they discover an unforgiving, inhospitable landscape of volcanic rock that precludes much exploration beyond the confines of the facility. But this message—if that is indeed what it is—gets filtered through the funhouse mirror of watching the scenario played out by an all-dwarf cast, manipulating the viewer into giggling at the childlike innocence of the little people only to choke back their laughter when they act hideously monstrous toward one another and nature. But there doesn’t really need to be a takeaway besides Herzog’s nascent talent for staging uncanny scenes that seem pulled from surreal nightmares—the dwarves searching across the volcanic terrain for a nebulous sound; dwarves on tip-toe, sneaking up on their blind companions to play a cruel trick; a cigar box containing the dried husks of dead beetles dressed up as if for a wedding ceremony. The parade of trippy imagery is dense and unnerving, and can be appreciated purely for its evocative poeticism and aesthetic qualities. This ensures you won’t forget the film for a long time, even if the barrage of symbolism and metaphor don’t cohere into anything worth pinning down.

Fifty years on, Even Dwarfs Started Small would be lost to time if not for Herzog’s sustained success in the realms of fiction and documentary filmmaking. As is frequently the case, the stories of Herzog’s on-set antics are perhaps more interesting than the film itself, and are some of the earliest anecdotes upon which the mythology of Herzog is built. At one point, a dwarf caught on fire, and the director dove on top of him to smother the flames. The cackling dwarf bound to the office chair was instructed to keep a straight face, only for Herzog to make faces at him from behind the camera to elicit laughter. When one of the actors got hurt filming the scene with the driverless van (which was inspired by Herzog’s stint as a parking attendant), the director promised that if they made it through the shoot without another injury he would dive headfirst into a cactus patch—which he did. In an interview years after the project, he claimed there were still bits of cactus spine stuck in his knee. “It’s not self-destructive to jump into a cactus, it was just showing them that I had an awareness of the problems they had and giving them some fun in exchange.”

Herzog has stated that film is “the agitation of the mind,” and Even Dwarfs Started Small achieves that end quite effortlessly. It will certainly not be everyone’s cup of tea, but a film that gets banned in its director’s home country is one worth taking a glance at.