“Hey kid. You want to spar a little?”

Boxing is a sport that fits cinematic storytelling like a glove. The dramatic narrative arcs associated with the genre, whether that be exorcising internal demons, overcoming rough upbringings, or wallowing in self pity while pining for the golden years, can be made physical and brought to a climax inside the ring. Following the conventional Hollywood formula, many of these films depict the rise of an unlikely hero and end in euphoria as the underdog hoists his new championship belt in victory.

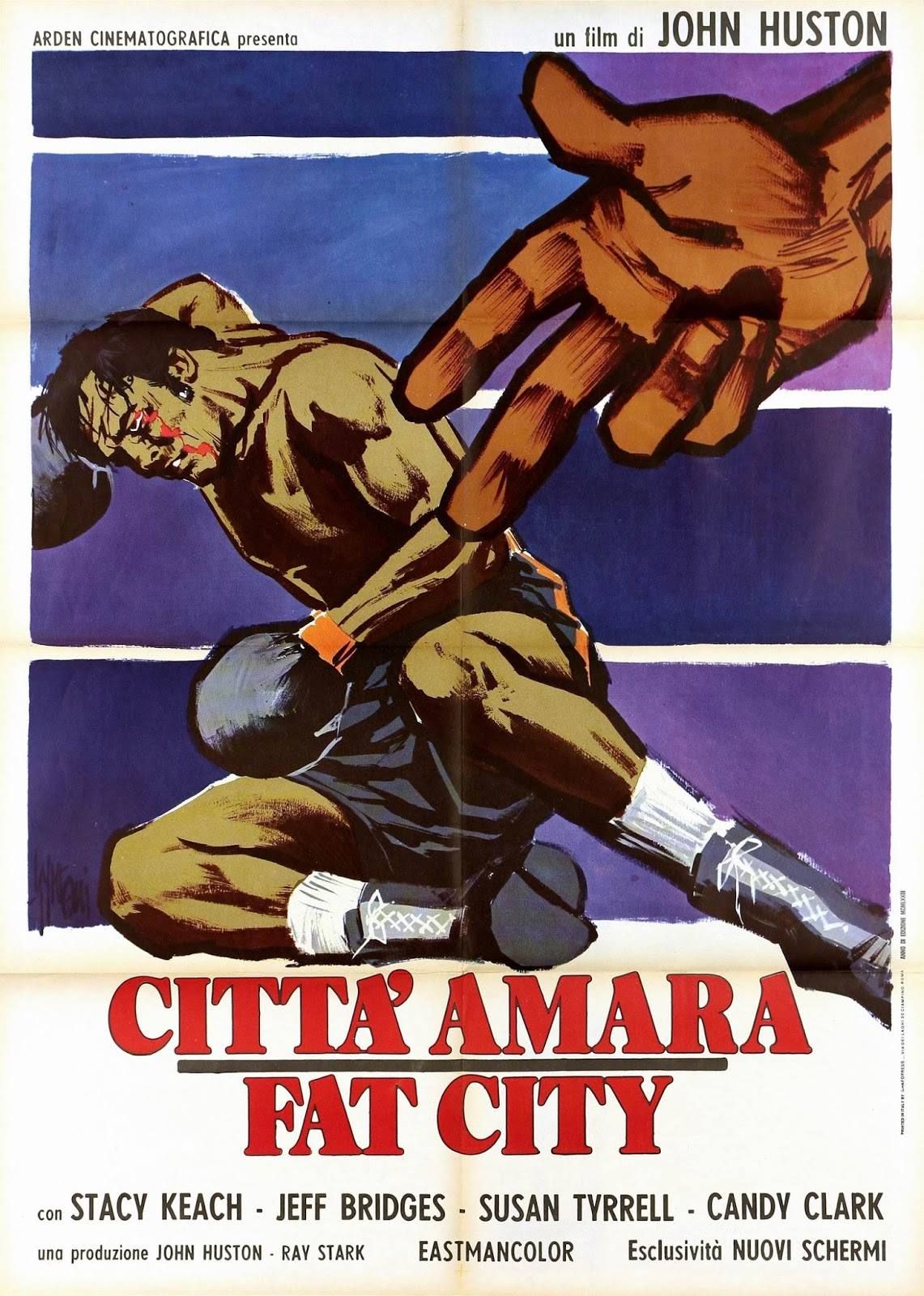

Fat City, adapted by Leonard Gardner from his own novel, doesn’t feature any champions. Rather, it documents the struggles of two third-rate boxers who toil away in poverty and repeatedly get the snot beat out of them without a chance that they’ll make it big. Their career opportunities are limited and they’ve tasted small victories, so they return, wearied and malnourished, to exchange haymakers with a similarly downtrodden foe until one of them can no longer stand. Absent a gripping rags-to-riches story, it relies on strong characterization and a pessimistic depiction of the amateur boxers’ unenviable way of life to connect with the viewer.

Featuring the relatively unknown Stacy Keach and a young Jeff Bridges, the film was a return to form for director John Huston, who was coming off a string of poorly received efforts. Indeed, it is not difficult at all to see the parallels between Keach’s Billy Tully and the out-of-favor filmmaker, even if we momentarily ignore the fact that Huston himself was a top-ranked amateur boxer in the olden days (as was Gardner). Tully is a former contender whose passion is re-ignited when he spars with young aspirant Ernie Munger (Bridges). Likewise, Huston’s star had faded considerably since his early triumphs (The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre), and he was witnessing a new generation—the New Hollywood mavericks—blaze a fresh trail in the cinematic medium. Fat City does not look like the work of a man stuck in his ways, but of a fresh and exuberant talent looking to make a name for himself in a new era of filmmaking. Unlike his central character, Huston was able to parlay that inspiration from the younger generation into a late career renaissance that lasted another dozen or so years (Under the Volcano was nominated for the Palme d’Or in 1984).

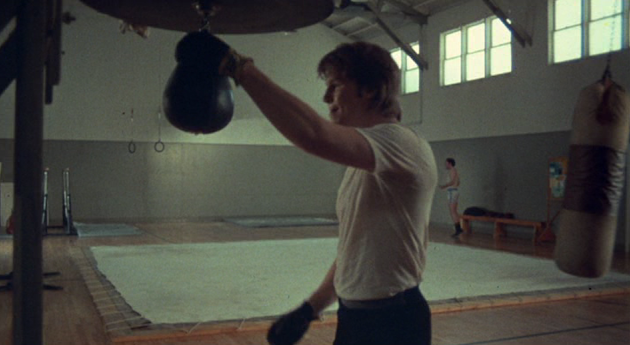

The melancholic tone of Fat City is set during the opening frames. Shot in Gardner’s hometown of Stockton, California, where the novel is set as well, we watch the city’s impoverished residents begin another day of mundanity as the opening credits roll. Kris Kristofferson’s wistful ‘Help Me Make It Through The Night’ plays softly as Billy Tully awakes from his slumber in a dilapidated apartment. An unshaven face, unwashed clothes, a cigarette in bed, and a hangover slowness to his movements quickly reveal the hopeless state of the washed-up fighter. He shuffles out into the midmorning light before heading back into the apartment, grabbing his dusty old gym bag on a whim and moseying to the YMCA. He finds the gym deserted save for a youngster named Ernie Munger, a local kid who’s never boxed before but takes the former pro up on his offer to spar. Impressed by his raw talent, Billy recommends that Ernie seek out his former trainer, Ruben (Nicholas Colasanto), encouraging him that he has the natural ability to become a contender himself.

Here is where you’d expect the story to really take off—the paths of the veteran and rookie briefly crossing before diverging and then coming together again. Ernie will immerse himself in a world that Billy can’t hang with anymore, steadily improving under the tutelage of Billy’s former trainer. Inspired by the prodigious talent he discovered, Billy will whip himself back into fighting shape, and at least win back his wife if not his professional status. But Fat City subverts conventional expectations. Ernie does go to see Ruben. He trains with youthful determination and professional guidance. But he gets his nose broken in his first fight and never amounts to the vision Billy had of him. He basically becomes a run-of-the-mill nobody, as likely to go the distance and eke out a win as to get KO’d twenty seconds into a fight. He soon finds himself marrying his accidentally impregnated sweetheart Faye (Candy Clark) and working in the fields alongside Billy to provide for his family.

Billy, meanwhile, has been shacking up with a barfly named Oma (Susan Tyrell) while her man does a stint in prison, vainly trying to fill the hole left by his wife’s departure with another woman and copious amounts of alcohol. Oma’s own alcoholism endears her to Billy but also serves as fuel for a growing sense of hatred between them. As Ernie’s brief tenure as an amateur appears to be on the wane, Billy manages to get a fight scheduled in between his days-long bangers. He’s in no shape to be fighting, but neither is his opponent, an aging Mexican who suffers from an internal injury that sees him peeing blood in the locker room before the fight and falling unconscious in Billy’s arms when the pain becomes unbearable. Though he wins, Billy fails to find any sense of achievement or catharsis in his victory; a triumph made hollow because it cannot fill the true void in his life.

Fat City is a decidedly bleak affair that carefully avoids any sort of redemptive arc. Our main character dives headfirst into self-destruction and his only instance of positive behavior is superficial and ultimately worsens his outlook on life. Keach embodies the down-and-out role so completely, from mannerisms to looks, that it’s startling to think that Huston initially tried to snag Marlon Brando for the role. But what really makes Fat City stick is its supporting cast, which Huston offers ample screen time to develop their own characters. Chief among the secondary players is Susan Tyrell, whose perpetually drunken Oma matches Keach’s abrasive Tully at every turn and earned her an Academy Award nomination. There are several drunken conversations between them where Huston just lets his camera run without cuts that are simply magnificent pieces of cinema. Elsewhere Huston allows bit parts to expand in service of levity, including some silly banter between Ruben and his assistant Babe (Art Aragon), a pre-fight pep talk from Buford (Wayne Mahan) before both he and Ernie get whooped, and a story from a fellow field hand about how wine and roses caused him to lose his wife. These diversions don’t necessarily inform our leads, but they create a fleshed out world where everyone is in similar states of despair, praying that they can just make it through the night.

In that light, Fat City is less concerned with boxing than with elucidating the baseline brokenness of the human condition. The people that color in its margins understand the American Dream in theory, and speak with a language that pretends they can achieve it—but they exist in a default state of poverty and cannot truly fathom bootstrapping their way out of it. And so they turn to booze and cheap sex and half-hearted dreams of glory that will inevitably be shattered because they lack the means and grit to realize them. The film concludes with a suggestive finale at an all-night diner where our two boxers sip coffee since Ernie won’t drink alcohol. “Before you can get rolling, your life makes a beeline for the drain,” Tully says. “Do you think he was young once?” he asks, referring to the slow-moving nonagenarian who served them. As he turns around to survey the room, the bubble of realism is momentarily ruptured as the sound drops out and the frame freezes, the smoke from a waiter’s cigarette hanging still in the air. Tully’s had some sort of epiphany, and when Ernie tells his friend that he needs to leave, Tully pleads with him to stay and talk awhile, even though he has nothing to say after his moment of clarity. Then Kristofferson chimes in again: “Yesterday is dead and gone.”