“Why didn’t you tell me there were mysteries? You stood in that church and explained them away.”

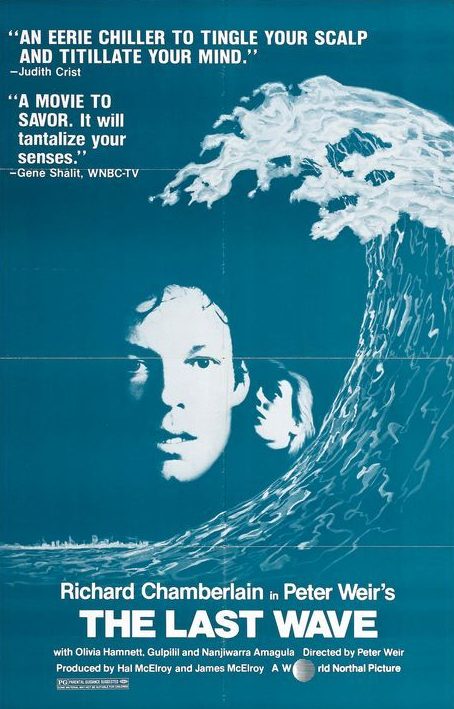

Peter Weir’s The Last Wave is an intriguing blend of legal drama and spiritual horror—an odd mix that should feel awkward, but Weir makes it work, his story brought to life by fine acting, an unorthodox soundtrack, and a confident handle on how to frame and edit depictions of existential uncertainty. Our protagonist is David Burton (Richard Chamberlain), a corporate taxation lawyer who finds himself defending a group of Aboriginal men that are being charged with a man’s murder. Things turn strange when David meets one of the accused men, Chris (David Gulpilil), recognizing him as the figure who’s lately invaded his dreams. As the case unfolds, David finds himself desperately trying to comprehend phenomena that defy a strictly legal explanation: he feels a mystical connection to Chris, a personal role in the increasingly bizarre weather patterns, and a vague sense of participation in the transcendental Dreamtime.

The film begins with a short series of vignettes displaying unusual weather conditions throughout rural Australia, indicating a disruption in the cosmological order. In the very first, we observe a clear blue sky paired with thunderclaps, before a rapid hailstorm begins pummeling a schoolhouse. In another, we follow a man frantically running through a series of underground tunnels. We cut to the same man awakening in a lively pub, where some many patrons are waiting out a downpour. But when a group of Aboriginals enter, the man runs again, out into the storm, now dogged by pursuers. But then he stops on a dead in his tracks, held in place by the sight of a bearded man sitting in a car, staring at him from the shadows.

We linger here to witness a uniquely chilling scene. It is not immediately apparent what has occurred, but the man clutches his chest as his pursuers begin to congregate around him. It is unclear if he has been shot or is perhaps suffering a heart attack. As neon signs flash on and off in the twilight rain and the Aboriginal gang crawl over city rubble in silhouette, the soundtrack drops out and the film falls into slow motion. The man slowly collapses to the primally unnerving sound of a rhythmically pulsing didgeridoo. From the car, we see a bone wand slowly withdrawn. It had been extended in the direction of the dying man.

Although an expert in corporate taxation, David is looped into representing the accused men a government initiative. He is uncertain exactly how conventional laws apply to the tribal Aboriginals, who no longer live in the city and operate by their own set of primitive laws which involve arcane rituals handed down from the forefathers. After meeting with the accused men and examining the available evidence, David concludes that the murder was tribally motivated, but remains unsure of precise motives or how the deed was actually carried out. The court case, which aspires to ascertain the facts of the matter, cannot truly approach the reality of the Aborigines’ tribal killing. The civilized law and the Aboriginal law share so little common ground that the tribal men placing their hands on the bible and swearing to God means absolutely nothing to them.

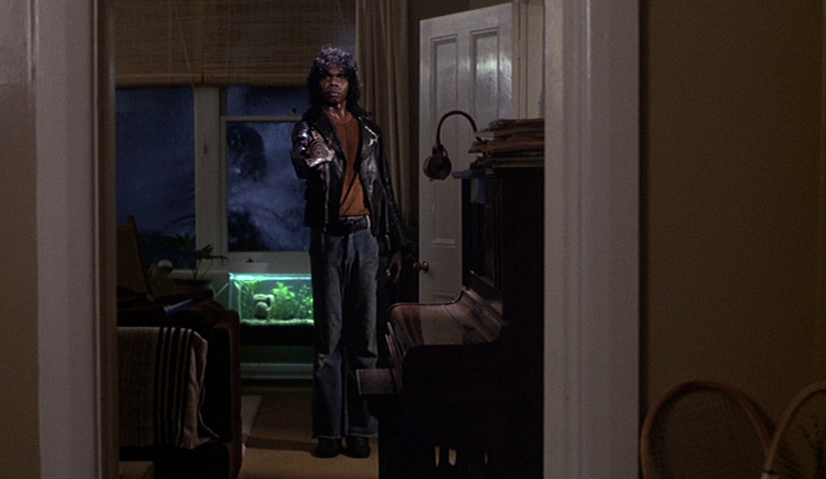

David is skeptical of his own abilities, but he continues with the case to sate his curiosity. Things take a turn for the bizarre when in an episode of insomnia-induced lucid dreaming, he imagines that an Aboriginal man is inside of his house, arm outstretched toward him, holding a triangular stone with tribal carvings and blood on it. It turns out that this is Chris Lee (Gulpilil), the only accused man who David hadn’t met yet. Once he meets Chris and connects him to the figure from his dream, David’s life and his understanding of the world around him begin to rapidly unravel. Proudly rational—what lawyer isn’t?—David gradually comes to realize that every external event and every internal thought are gathering into a predetermined course.

David meets Charlie (Nanjiwarra Amagula), the wielder of the bone wand, and we are given a vague overview of the Aboriginal mythology that undergirds their worldview. The film treats Aboriginal beliefs legitimately, which was conditional for Nanjiwarra’s acceptance of the role. The tribal Aboriginals are unalarmed by the erratic weather, and in fact, expected it. They are subservient to a power they understand to be greater than themselves. Representing Western political/social/spiritual views, David asks, “But surely men are more important than laws?” Chris, the mediator between the shaman and the lawyer, replies, “No. The law is more important than just man.”

Chris explains their mystic beliefs in telepathy and the reality of the dream world, tugging on the skin of his arm in demonstration of the deep spiritual connection that allows him to communicate with his brothers from a distance. David becomes consumed with unveiling the Aboriginal beliefs and discovering his own role in the events that are happening, believing that his nocturnal hallucinations and the erratic weather patterns indicate an impending apocalypse. It is unclear whether most of the struggle is real or taking place within David’s mind, but what is clear is that David has fundamentally changed. Reaching back into his past to decipher old dreams and memories, he concludes that he is and has always been a medium through which the “Mulkurul” interacts with humanity. When he speaks with his father, a clergyman whose strict dogmatism prohibits the examination of such mysteries, he tells him, “I’ve lost the world I thought I had.” In the climax, as he kneels on the beach, crestfallen, David gazes toward the titular ocean swell as its shadow darkens his face, and we do not know if it is the end of the world or just the end of him.

Living in an era of secularist culture, it is refreshing to see the belief system of another culture considered so fairly here. Weir chose not to use urban Aboriginals in the film, instead opting to cast legitimate tribal men in the roles. Nanjiwarra was a real shaman and tribe elder, and his condition for accepting the role was that their belief in the superiority of the law be evident in the film’s text. This clearly differs from our modern perspective, where any law that doesn’t serve us is ripe for scrutiny; there is nothing sacred, nothing eternal, nothing greater than the individual. It is equally refreshing to be reminded by Weir’s thoughtful mise en scène just how little ability we humans have to exert control over our environment. We have roofs and windshield wipers umbrellas and faucets and basins and swimming pools, but when nature rears its chaotic head no buttress will stop the last wave. If I must pick nits, I would suggest that it is too easy to use a man of the cloth as a foil for the Aboriginal spiritual worldview; too easy because doing so uses a stereotype to represent a religion that, in many circles, considers such worldviews as legitimate (in the sense that “false gods” are not “fake gods”).

While Weir has always been gifted in terms of using every facet of his craft to evoke psychospiritual states in the viewer (see Picnic at Hanging Rock, Fearless), I think the soundtrack of The Last Wave is worthy of special recognition. It is not enduringly popular. It does not feature anything that would qualify as an earworm. But it is exceptionally creative in the sense that someone at some point had to have been bold enough to suggest that they attempt such an unconventional approach. Much of the film is bolstered by tracks similar to the synthesized drones of Klaus Schulze or Tangerine Dream which are adequate if not especially unique. However, what is most notable and exciting here is the repeated use of a didgeridoo, which plays during many of the film’s most intense moments, imbuing them with a sense of alien fear. The idea of suprarational mysteries existing beyond the scope of our conception of the world, and civilizations inability to totally repress them, will certainly remain with me, but that unsettling sound will endure as well.