“What have I unleashed?”

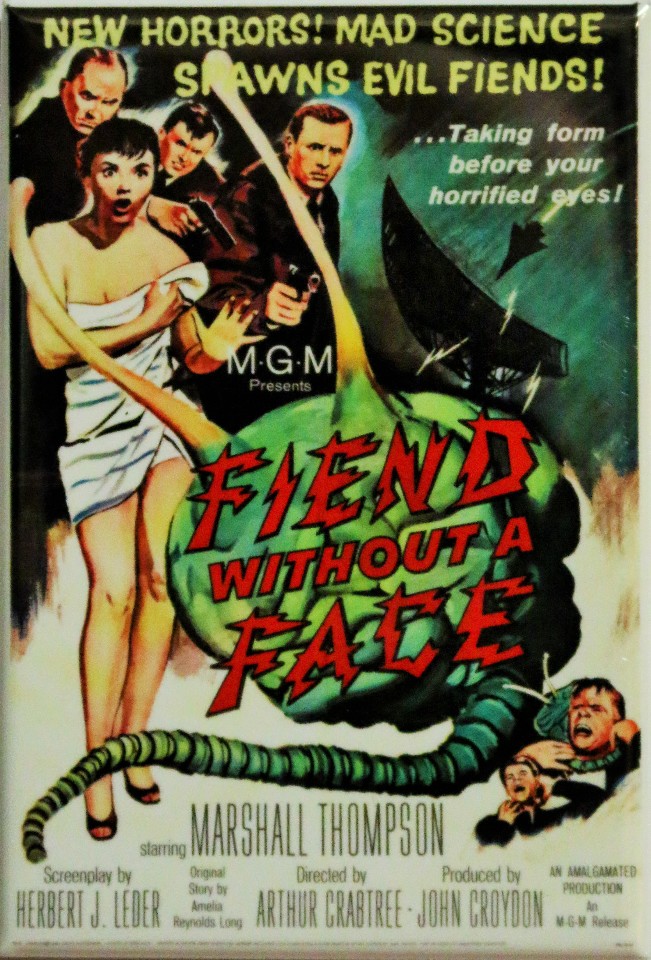

Arthur Crabtree’s Fiend Without a Face is a fun mystery from the atomic era of sci-fi horror films. Experimental military radar systems, nuclear radiation, disappearances, and unexplainable deaths gradually build up a sense of terror in a Canadian town as the titular fiend claims more and more victims. Years before Night of the Living Dead, it features a very similar board-the-windows vibe, though it is much less iconic than that film for a number of reasons. The film was quite controversial in its time,1 and it was promoted by placing the brain-and-spinal-cord-looking monster into a glass case and displaying it outside a theater in Times Square, where police had to break up the event because the crowd was blocking traffic. It’s an interesting time capsule of the social climate and the varying attitudes toward nuclear power, as well as the stigma surrounding experiments with the paranormal. Though it is probably doomed to the landfill of cinematic history, it was enjoyable enough for its brief 74-minute runtime.

The plot concerns a malfunctioning experimental radar station that uses nuclear power to spy on other nations.2 The small Canadian farming village which is home to the base begins experiencing a series of deaths, all characterized by two small puncture wounds at the base of the neck, through which the coroner tells us that the brain and the spinal cord have been sucked. Major Jeff Cummings (Marshall Thompson) begins interviewing townsfolk to uncover the cause of the deaths, honing in on Professor Walgate (Kynaston Reeves) when he discovers that the retired researcher has been writing about and experimenting with telekinesis and thought projection. Walgate eventually admits that by syphoning power from the nuclear reactor, his enhanced thought projections got out of hand and created an invisible, and apparently evil, entity.

There is, of course, a romance to fill out the story. Walgate’s assistant, Barbara (Kim Parker)—sister of the first victim—finds herself crossing paths with Major Cummings quite often as the plot unfolds. Though the story beats are clichéd and predictable, I thought Parker’s presence was enjoyable throughout. I particularly liked a scene in which a town council is called to discuss forcing the military to remove themselves from the area because, according to the townsfolk, the problems only started when they arrived. They claimed the cows weren’t producing milk like they used to because of radiation. Barbara, whose brother was a dairy farmer, speaks up and sets the record straight, stating that they are merely scared of the airplane activity, not affected by nuclear radiation. Unfortunately, it looks like Parker had only been in a few films prior to Fiend (Fire Maidens from Outer Space and The Man Without a Body sound like tasty slices of B-movie cheese based on the titles alone) and stopped acting the year after.

The most noteworthy element of this film is the stop-motion animation. For a low-budget horror film, I can’t imagine a decision to include such an effect was taken lightly. Granted, the monster remains invisible for a large portion of the film, but when it does appear, it is all sorts of creepy, slimy, and nasty. Leading up to the reveal of their ghastly appearance, we see their presence only when they displace various objects—buckets of water, brooms, straw, carpet—and strangle their victims. Once they are visible, though, there are a surprisingly large number of shots that include characters shooting the creatures and blood oozing from them, as well as their eventual disintegration into puddles of mush when they are finally defeated (this gross imagery is one of the reasons it was controversial for its time). In a few scenes, there are several of the creatures on screen at one time, and the imagery, combined with the stop-motion and sound effects, becomes quite surreal. The gross creatures and their organic sound design seem to point toward the early work of David Lynch, including the cult classic Eraserhead.

The use of light and shadow is worth noting, in particular in several indoor scenes in which silhouettes are projected onto the walls. It’s entirely unrealistic but adds a lot of character to the images. There’s also a shot during the midnight manhunt for the deranged killer (when the fiend is still invisible and unknown) in which the light illuminates only the contours of the hunters.

The film falters mightily in its third act. After the intriguing buildup and gathering of clues—all fairly conventional, of course, but done very well—the mystery is not uncovered by the protagonists, but explained to us by Professor Walgate, which saps much of the momentum from the plot. As he sits in his armchair describing his actions, his monologue becomes a voiceover as clips of him conducting his experiments play for the audience. The concept of thought projection creating an entirely new entity is a neat idea for a horror film, but the explanation of it could have been woven into the rest of the story much better.

When considered in its era and context, this film is very good, and maybe even pushed the envelope a bit with its stop-motion effects and heavy use of gore in its finale. But it’s not a classic or any sort of seminal sci-fi/horror film.3 It’s just a competent, flavorful, and occasionally surreal sci-fi film from the Atomic Age. Nothing wrong with that.

1. Fiend Without a Face was made while the Hayes Code was still in effect, so sex, blood, and cursing were usually minimal. Don’t get the wrong idea (that this film is some long-lost gem that pre-dates the excessive tendencies of some New Hollywood directors), this is still very tame by modern standards. But it caused a stir back in the day and includes a bit of gore and some risque scenes.

2. It’s not really explained how exactly this works, other than “nuclear power” which was kind of how the general public viewed nuclear power in that era. People thought you would be able to drive a car for thousands of miles using a capsule the size of a daily vitamin. So while it seems like the concept is just a silly idea included in a movie, it wouldn’t be surprising if the audiences actually thought this was possible when they first saw the film on its double bill with The Haunted Strangler.

3. And it doesn’t have to be one, but that’s how Criterion presents most of their releases, including this one, calling it a “high-water mark in British genre filmmaking.”

Sources:

Lambie, Ryan. “Fiend Without A Face, and its surprising controversy”. Den of Geek. 21 October 2015.