“You’re just guilty. You’re gutless and you’re guilty.”

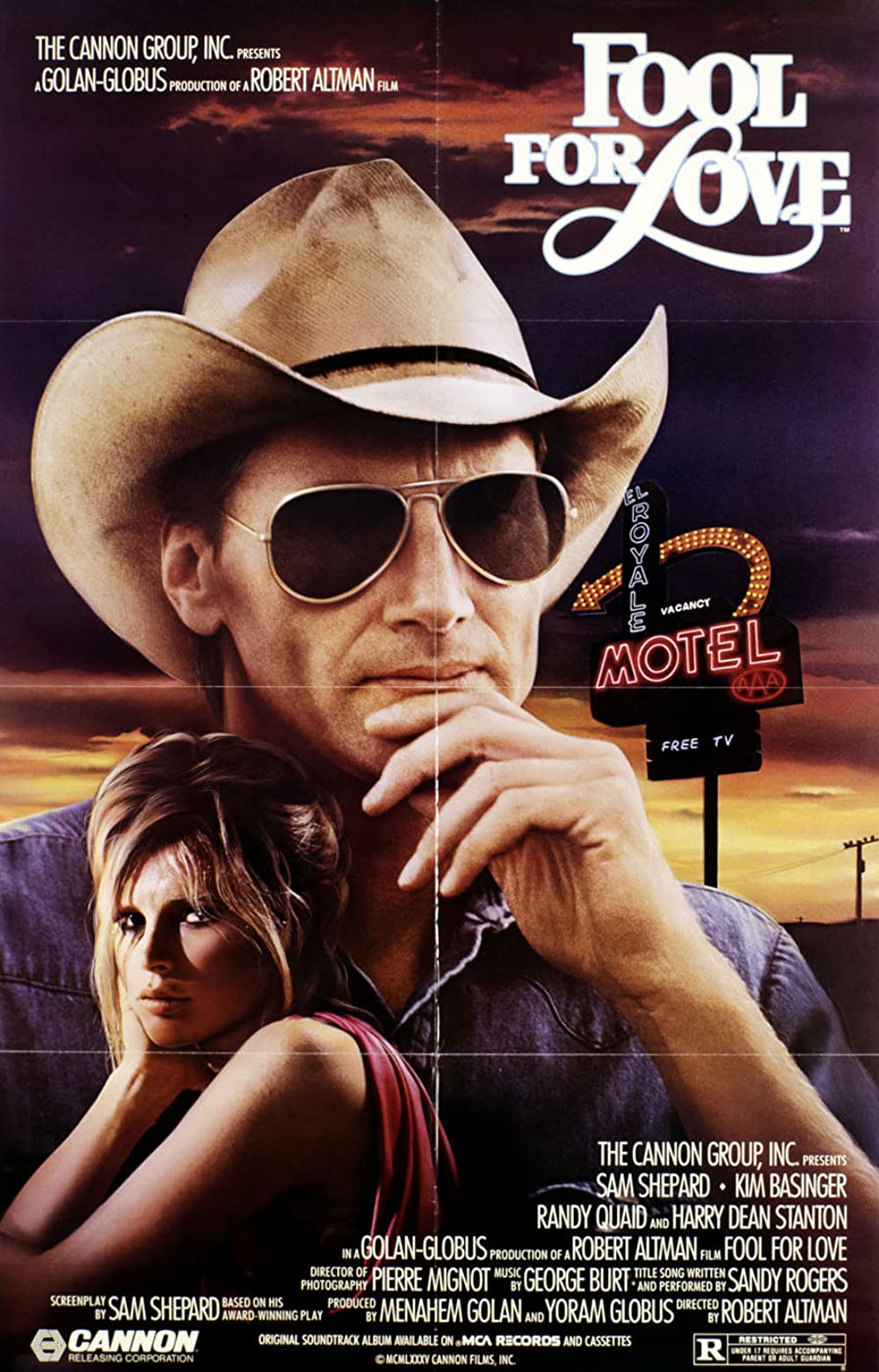

Robert Altman was no stranger to translating works from the stage to the screen when he teamed up with Sam Shepard on Fool for Love. The 1985 film came in the midst of a low key decade that found the mercurial director operating outside of the Hollywood system, self-financing or working with independent studios to make literate chamber dramas on shoestring budgets. It was the fourth play adaptation from Altman, following the protractedly-titled Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, and the critically lauded Streamers and Secret Honor.

A kinky slice of rustic Americana funded by, of all people, Golan and Globus of Cannon Films, Fool for Love often gets overlooked in favor of Altman’s major films. The lack of attention is understandable. There’s a smallness and constraint to the story that precludes it from matching the sprawling achievements of the director’s most notable works, and Shepard’s script, while frequently piercing and finally haunting, might have benefited from some additional polishing. But even so, Altman imbues the picture with evocative visual and aural poetry that transforms the ramshackle motel setting into something marginally surreal and otherworldly—not groundbreaking, per se, but compelling in its strangeness. The way that the director merges past and present, and deftly, subtly stages multiple perspectives of a situation concurrently, all while allowing his actors the freedom to fully inhabit their combustible characters, is the work of a true master.

While Shepard and Altman are both indispensable when it comes to the artistic exploration of the contours of the American psyche, they’re decidedly dissimilar in their approaches. Like his camera, which meanders distractedly, paying cursory attention to the drama but always fascinated by the peripheral details, Altman’s characters are erratic and uncalculated. This stems from the director’s tendency to treat the screenplay as a mere suggestion and encourage his actors to own their characters through improvisation. Conversely, Shepard’s are usually well drawn archetypes, loiterers predisposed toward picking at some half-healed scab or long-buried subject. In Fool for Love, Altman elects to treat Shepard’s screenplay with great fidelity—a wise and perhaps mandatory decision considering his insistence that the playwright himself take on the lead role in wake of his Oscar nomination for The Right Stuff.

Shepard plays Eddie, a loose cannon cowboy type who drives a decayed pick-up truck thousands of miles across the country to an isolated motel in the Mojave Desert; a ramshackle cluster of shanties marked by crumbling façades, flickering neon lights, and small mountains of rusty cars, mattress springs, and other junk sprawled out back. Waiting for him there—no, hiding from him there—is his ex-lover May (Kim Basinger), a despondent, trailer trash beauty who can’t decide if she loves or hates him. She’s elected, for the time being, to cook and wash dishes and change sheets in an attempt to escape the self-destructive cycle of behavior that she’s shared with Eddie for so long. But of course it’s hard for her to work through these conflicted feelings when the man himself has just rammed his shoulder through her motel room door. What follows is a wild tangle of confusion, desperation, anger, and sexual attraction released in a gush of bluster and bloviation.

Hovering over the fiery proceedings is the Old Man (Harry Dean Stanton), a shabby fellow who spends his time hunkering down in his dilapidated mobile home, anxiously milling around the innards of the motel office and kitchen, and playing his harmonica. He seems to observe the lovers’ savage ritual with relish and apprehension. As we’ll learn, in addition to believing he’s married to Barbara Mandrell, the Old Man happens to be the father of both Eddie and May—I said it was kinky, did I not?—a juicy tidbit that comes to light when May’s new man, a dopy boy scout named Martin (Randy Quaid), arrives with the intention of taking his sweetie to the movies and begins to wonder aloud just how this rowdy Marlboro Man relates to his darling May.

The acting, especially from the two leads, is enthralling. Basinger handles herself with great poise as May becomes emotionally twisted and finds herself oscillating between tones of tenderness and venom just as often as she changes outfits. Likewise, Shepard’s a real live wire, playing his voyeuristic, hair-trigger cynic with just the right amounts of vinegar and charisma; you’re never quite sure how he will react to each new development.

There’s a feeling hanging in the air after the initial chapter, once we’ve come to understand the basics of the pair’s history and settled into this pocket of despair out in the middle of nowhere, that the audience is in for nothing more than turgid melodramatics—not necessarily a bad idea in the hands of Altman, Shepard, and Basinger, but also not the most enticing recipe either. The film is spared such a fate by two elements that are somewhat related. The first is the comedic undertone that erratically comes and goes in typical Altman fashion, dropping out for long stretches but then popping up for a surprise knee to the groin or a biting rhetorical question spat with real menace when Eddie’s rebound, a wealthy gal dubbed the Countess (Deborah McNaughton) drives right up to the motel and starts firing a pistol into the lobby. Previously, Eddie had pestered May about her relationship with Martin. “Have you balled him yet?” he had teased. Now, under the threat of gunfire, he pulls May to the ground as bullets whiz above their heads. “How crazy is that chick?” May asks. “She’s pretty crazy,” he says. “You just stay down.” She fixes him with her accusing gaze. “Have you balled her yet?”

The second element that elevates Fool for Love above its modest melodrama is the way it gradually relinquishes the notion of truthful storytelling, even deliberately muddying the waters at times through flashbacks, repetitions, and vaguely incongruous actions. Further, slowly at first and then with a feverish intensity that calls to mind the work of David Lynch, it releases its grip on the reality of the image itself. Throughout the first two-thirds of the film, we were more or less tethered to the ground, the dreamlike quality of the neon-lit motel complex and the husky croon of Sandy Rogers notwithstanding (much of the music is diegetic anyway, not to mention terrific). But even in the early going, the Old Man feels detached from the film, flitting around on the periphery and observing but never clearly tied into the story. At first we question his identity, then we question his existence. Perhaps his presence is only spectral in nature, his ghost only visible to his offspring. Once Martin arrives and the macabre revelations spill out with increasing rapidity, the film transforms into a Rashomon-esque recitation of the Old Man’s two-timing habits that led to his son and his daughter unwittingly fooling around in high school. Eddie and May each retell the tale with conviction and yet the stories don’t jibe. The truth of the matter is confused even further by associative editing and narrated flashbacks where the actions don’t match the storyteller’s memory.

Delightfully, the climax of the film doesn’t lead to any real resolution. The revelation of the half-siblings’ dark secrets does not result in catharsis or reconciliation but a further splintering that grimly sends everyone on separate solitary paths, leaving loose ends narratively and thematically. Humble and shambolic, yet layered and confidently rendered, Fool for Love might be a minor work in Altman’s canon, but it’s a still a formidable film in and of itself and it’s mystery to me why it hasn’t gotten the retrospective attention many of the director’s other films have received.