“God’s not on our side because He hates idiots.”

The Man with No Name is an odd title for a man who has, over the course of three films, gone by Joe, Manco, and now Blondie. If anything, he’s the Man of Many Names—a more fitting moniker for the focal point of a loose trilogy of films that doesn’t even pretend to string together an ongoing narrative. Indeed, Sergio Leone’s three initial Westerns unfold more like a fever dream of recurring images, scenarios, and themes, with Clint Eastwood’s stoic, lethal drifter persona as its constant. The clearest point of disconnect is Lee Van Cleef, who, having already portrayed the methodical angel of vengeance in For a Few Dollars More, returns in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly as Angel Eyes, a serpentine killer whose unchecked sadism clearly distinguishes him from the righteous bounty hunter of the previous film. Continuity is for chumps, or so Leone seems to think—and who am I to argue?

In The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Leone ditches the lean frameworks of the previous two films in favor of a sprawling and anarchic tale that weaves it titular scoundrels—including newcomer Eli Wallach’s Tuco—into a Civil War backdrop that’s so grand it threatens to swallow them up, reducing them to the point of caricature, squinting and grimacing faces to be positioned within the sinuous, sensual flow of Leone’s bravura moviemaking. It’s not really about the war itself; Leone’s concern for historical accuracy matches his concern for spatial and narrative continuity. Like Lawrence of Arabia, the intimately drawn characters participate in an epic clash larger than themselves, but unlike that film, their actions do not have much effect on the larger stage. Instead, the peripheral chaos of apocalyptic battlefields, and Catholic missions brimming with corpses and sundry wounded, serve to amplify the animosity and dread slowly building among the three amoral leads.

Amoral indeed, for though they receive their freeze-frame designations as the Good (Eastwood), the Bad (Van Cleef), and the Ugly (Wallach), that’s all relative—each one is colored with various shades of bad and ugly as they operate on a spectrum from cynical opportunism to plain malice. None of them reinforce the John Wayne cowboy hero archetype, which is not to say that the film glories in depravity but that it builds out its myth without the white hat slant of the Westerns of yore. One of the film’s many achievements, then, is that all of these men are perversely charming. Wallach is particularly likable as the mendacious, cantankerous, witty, desperate bandit who spends most of his time bound or cuffed or hanging by the neck but rarely shuts his mouth, as loquacious as Blondie is laconic. We’re never quite sure if he is actually a clown or just playing one to get himself out of his current predicament.

In fact, Wallach brings an unexpected dose of comedy to the proceedings and is the star of the show. Many of the film’s scenarios could be grim, but Wallach’s manic presence elevates a brutal drama into a sublime entertainment. The film begins with Blondie and Tuco running a con where the former “captures” the latter, turns him over for a reward, and then shoots the hangman’s rope with a long range rifle, thus allowing him to escape. Rinse, repeat. They bicker about the split—Who should get more, the guy who’s hanging or the guy with unerring aim?—and we comprehend the gravity and the comedy of the situation. The story’s impetus is a buried cache of gold—Angel Eyes is tracking a man who knows its location, but he dies before they ever meet, his final words informing Tuco of the cemetery where it can be found and Blondie the name on the gravestone. And thus Blondie and Tuco are permanently if tenuously allied—not friends, exactly, but unwilling to commit to the demise of the other—a fact that does not dissuade Tuco from ceaselessly badgering Blondie for his part of the secret. Leone also amplifies this heretofore subdued element of comedy with his compositions and editing. In the first hanging scam, he lingers on the orator reading off the litany of crimes for which Tuco is being hanged. At one point, Tuco is literally caught with his pants down when his would-be killer confronts him while he enjoys a bubble bath; in the middle of his screed Tuco shoots him with a gun concealed by the bubbles. Angel Eyes flips coins to a legless soldier (José Terrón) who has eyes and ears all over town, and accepts offers from two men to kill the other then follows through on both errands. Even the awkward dubbing and whiz-bang foley effects tend to work in the film’s favor.

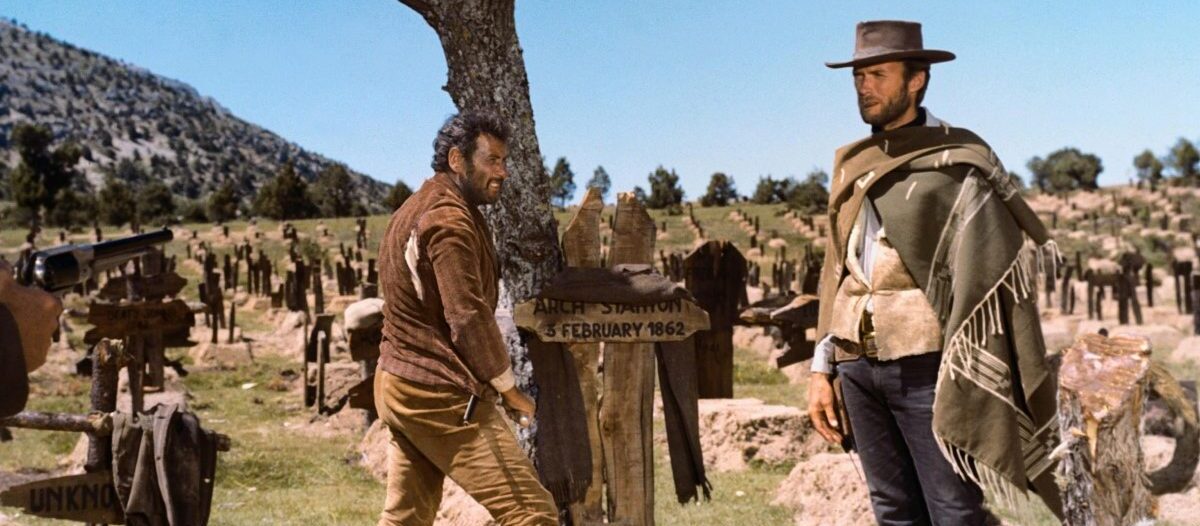

This playfulness loosens us up and puts us in a frame of mind where we can connect with the basic dramatic turns but also remain open to the resplendent flourishes—and Leone really outdoes himself here, expanding his style while firming up his grasp on it, cresting a zenith in the protracted Mexican standoff with all its sweaty closeups, magnificent cemetery setting, and overpowering, multifaceted score from the great Ennio Morricone (the eminently recognizable motif is perhaps more famous than the film itself). The entire film builds to this extravagant finale, not just narratively but stylistically, as Leone’s desolate vistas, simmering tensions, and Wild West iconography chemically combust with Morricone’s deranged screeching in one of the most iconic climaxes in the history of the silver screen.

One of the great achievements in narrative filmmaking, Sergio’s Leone’s extravagant, self-indulgent epic is a masterclass in audiovisual storytelling, even as it selectively bends and reshapes established rules of the craft. One wishes it had was a skosh less baggy and that Blondie’s latent moral fiber was a little more apparent, but even though I prefer the efficient mythmaking of For a Few Dollars More, there’s no arguing that The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is the one that transcends the Western genre and is rightly considered among the great treasures of cinema.