“They used to get around, walkin’ around, lookin’ at stuff. They used to try to find clues to all the mysteries and mistakes God had made.”

David Gordon Green’s George Washington is a languid mood piece concerning an eventful summer in the lives of a hopeless and impoverished group of adolescents as they begin to understand love and death. Shamelessly indebted to Terrance Malick’s Days of Heaven (and to a lesser extent The Thin Red Line), as well as Harmony Korine’s Gummo, the film’s wispy plot barely serves as a backdrop for a directorial debut largely focused on atmosphere and image.

George Washington hazily captures the feeling of a lost summer of youth, unsupervised and elegiac in its retrospection. An adolescent Nasia (Candace Evanofski) narrates the film as it unfolds, similar to Linda Manz’s role in Days of Heaven. Unlike Malick’s film, though, our protagonists never hop on a westward train to escape their doldrums; instead, they listlessly mill about the urban sprawl, seething and ruminating.

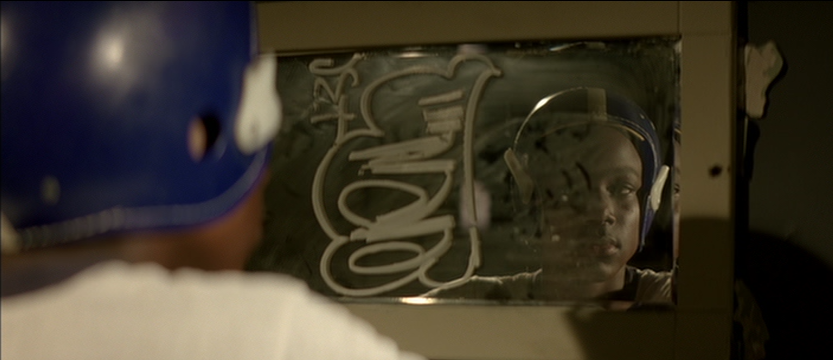

The enervated group consists of the laconic thirteen year old George (Donald Holden), who imagines himself to be a hero despite a medical condition that requires him to wear a maskless football helmet all the time, the temperamental Buddy (Curtis Cotton III), the slightly older and physically imposing Vernon (Damian Jewan Lee), the apathetic and sole caucasian of the group, Sonya (Rachael Handy), and the aforementioned Nasia. They spend their days wandering the streets, loitering at the train-yard, and investigating the abandoned buildings of their derelict town. The young actors are given dialogue which is often beyond their age and characters (like in Rian Johnson’s debut Brick), which can be quite jarring. Creative camerawork—slow motion, low angles, careful framing—along with Nasia’s voiceovers give the film a soft spoken poeticism that casually romanticizes the glum subject matter. The locations are full of decay and dead cultural artifacts, emphasized by an extended scene of trucks pushing garbage around at a landfill.

The film is largely plotless. The only crucial event is the accidental death of Buddy, which happens when the children are roughhousing in the bathroom of an abandoned amusement park. Nasia, who had recently broken up with Buddy because she was looking more a “more mature man” is the only one not there to witness it. The episode affects all of them in profound ways, altering their group chemistry and weighing heavily on their young minds. Vernon is racked by feelings of guilt. His barely coherent ramblings contrast with the unaffected demeanor of Sonya, who believes herself to be a fundamentally flawed person due to her indifference regarding Buddy’s death. George responds by trying to be the hero of his dreams—he wears a wrestling onesie, sweatbands on his wrists, his football helmet, and a bedsheet cape as he directs traffic.

“I just wish I had my own tropical island, I wish I was… I wish I could go to China, I wish I could go to outer space, man, I wish I had my own planet, I wish… I wish there were 200 of me, man… I wish… I wish I could just sit around with computers and machines and just brainstorm all day, man. Man, I wish I was born again… I wish I could get saved and give my life to Christ… then maybe He’ll forgive me for what I did. […] I wish there was just one belief… my belief.”

Though they feel the effects of their destitution, the children aren’t hopeless like their parents. George, in particular, is hopeful and optimistic. He saves a young boy from drowning, tests his sister’s response to his homespun fire drill, and catalogues the fire and electrical hazards at his uncle’s house. The film’s sentimental elements are buoyed nicely by its poetic tendencies. In addition to Nasia’s soliloquizing, at one point Buddy dons a dinosaur mask and gives an impassioned monologue on a disused stage; Rico (Paul Schneider), one of the trainyard workers, applauds the performance and asks, “Is that the Bible or Shakespeare?” (It’s the Bible; Job 29).

Throughout, Green experiments with juxtapositions of different styles and tones. Modern dilemmas are portrayed as alternately mundane and bemusing. Children try to act like adults while the adults betray their own inability to comprehend the world and its modern ills. But darkness lurks around every corner. In one of the film’s most unsettling scenes, George’s Uncle Damascus (Eddie Rouse) explains that his fear of dogs (and his reason for killing the homeless dog that George was secretly keeping behind the shed) was that he had been molested by a dog when he was a six year old boy. Like Gummo, George Washington is not about the story. It is about impressions and the framing of memorable images. Both films achieve this goal quite well, though the former goes quite a lot further in pushing the boundaries of decency. Its nihilistic surrealism and stylized aesthetic make it a more visually memorable film than George Washington, even if it is morbid.

George Washington is worthy of admiration, but not necessarily adoration. For a first time director to adeptly integrate his influences and operate in several different stylistic modes is laudable. The film’s consistently emotive scenes allow the disjointed narrative to gel somewhat. But there does seem to be a lack of intended meaning, like it is a half-finished creation that requires the viewer to fill in the gaps with their own experiences (which is fine, and many great films make use of that phenomenon too). The aphoristic monologues, while sounding eloquent and provocative, never really make a cohesive statement. And though the compositions are at times sublime, the subject matter is not especially visually compelling. An interestingly off-beat debut effort, and a refreshingly original and unconventional film.